Alcohol is so bad for society that you should probably stop drinking

Not something I expected to write

This post was inspired by similar posts by Tyler Cowen and Fergus McCullough. My argument is that while most drinkers are unlikely to be harmed by alcohol, alcohol is drastically harming so many people that we should denormalize alcohol and avoid funding the alcohol industry, and the best way to do that is to stop drinking.

This post is not meant to be an objective cost-benefit analysis of alcohol. I may be missing hard-to-measure benefits of alcohol for individuals and societies. My goal here is to highlight specific blindspots a lot of people have to the negative impacts of alcohol, which personally convinced me to stop drinking, but I do not want to imply that this is a fully objective analysis. It seems very hard to create a true cost-benefit analysis, so we each have to make decisions about alcohol given limited information.

I’ve never had problems with alcohol. It’s been a fun part of my life and my friends’ lives. I never expected to stop drinking or to write this post. Before I read more about it, I thought of alcohol like junk food: something fun that does not harm most people, but that a few people are moderately harmed by. I thought of alcoholism, like overeating junk food, as a problem of personal responsibility: it’s the addict’s job (along with their friends, family, and doctors) to fix it, rather than the job of everyday consumers. Now I think of alcohol more like tobacco: many people use it without harming themselves, but so many people are being drastically harmed by it (especially and disproportionately the most vulnerable people in society) that everyone has a responsibility to denormalize it.

You are not likely to be harmed by alcohol. The average drinker probably suffers few if any negative effects. My argument is about how our collective decision to drink affects other people. This post is not about what will happen to you if you continue to drink. It’s about what will happen to vulnerable people if you and I and others continue to drink.

Alcohol is a much bigger problem than you may think

The global disease burden is the most comprehensive single measurement of the total death and disability caused by disease. COVID caused 3.7% of the global disease burden in the first year of the pandemic before vaccines became widely available. In comparison, every year alcohol is responsible for 5.1% of the global disease burden. Alcohol is responsible for 1 in every 20 deaths worldwide each year, which is the same fraction as COVID.

Between 100,000 and 140,000 Americans die each year due to alcohol, which is 2–3 times as many people as are killed by guns in America each year. Drunk driving causes 290,000 injuries per year in the U.S. and costs society $132 billion per year, or $400 per year per person in the country.

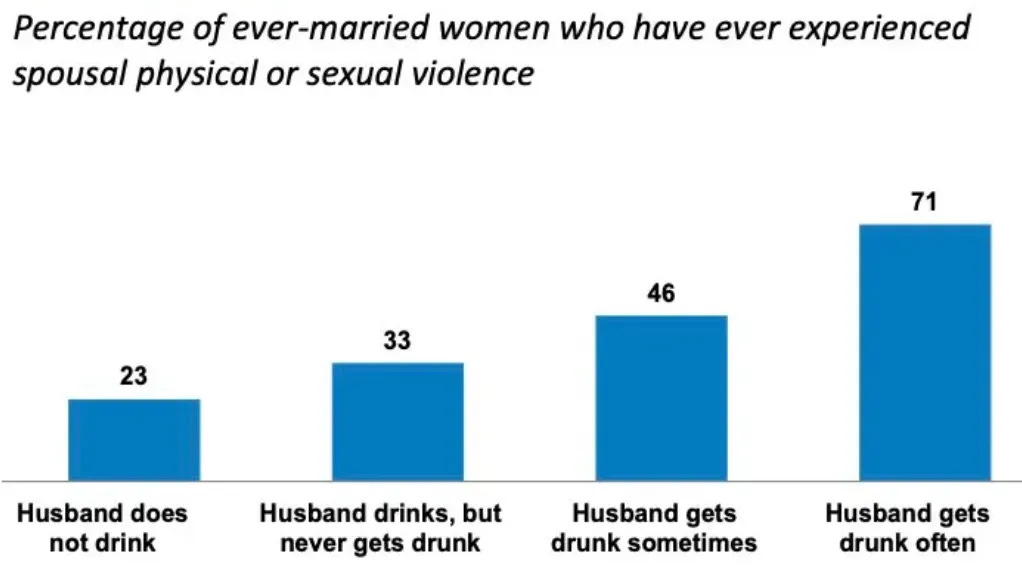

Alcohol probably makes people more violent. 30–40% of men who commit intimate partner violence were drinking at the time. 37% of sexual assaults, 27% of aggravated assaults, and 25% of simple assaults occur when the perpetrator is drinking. Half the people in American prisons had alcohol in their system when they committed the crime they were convicted for.

From Alice Evans:

Indian men’s alcohol consumption is the single strongest predictor of spousal violence. Regardless of wealth, education, employment or location, an Indian woman is much much more likely to be assaulted if her husband drinks. Indigenous Mexicans who drink every day are 13 times more likely beat their wives.

There may be more complex reasons why alcohol is correlated with violence, and it may be that reducing alcohol consumption wouldn’t have much impact on violent crime. However, if limiting alcohol consumption could lower these statistics by even a few percentage points, tens of thousands of Americans would be spared from horrific violence each year. There are some natural experiments on the effects of mass reductions in alcohol consumption. South Africa imposed a sudden and unexpected ban on alcohol in 2020 and injury-induced death fell by 14% and violent crime dropped sharply. This 2018 article on alcohol taxes summarizes the research on alcohol and crime:

Mark Kleiman, a drug and criminal justice policy expert at New York University’s Marron Institute, argues that the research on the alcohol tax is very clear.

“The single most effective thing you can to reduce crime right away is to raise the price of alcohol,” he told me. “If you talk either about crime policy or drug policy, that’s got to be the number 1 recommendation — just because it’s so easy. It doesn’t cost you anything. You don’t have to kick in anybody’s door. You just have to change a number in the tax code and crime goes down.”

Outside of the huge economic costs imposed by death, worse health, and violence related to alcohol, hangovers alone lead to $220 billion in lost productivity each year in the U.S., or $650 for every person in the country per year. Adding this number to the costs of drunk driving alone means that alcohol externalities are costing society over $1000 per year per person. Each person you know is effectively paying $1000 per year for alcohol to be a normal part of our culture, over and above the actual cost of drinks.

Alcoholism is really really really bad. It often (though not always) makes life hell for the people experiencing it and the people who depend on and care about them. Heavy drinkers who are not alcoholics still face shortened lives, serious harm to cognitive ability, and worse physical and mental health. While most drinkers do not become alcoholics, more do than you may expect. 1 in 8 drinkers are heavy drinkers, and 1 in 10 of those heavy drinkers become alcoholics. So at a minimum 1 in 80 people who drink will become an alcoholic. According to the DSM-5’s criteria, 1 in 10 drinkers have either moderate or severe alcohol use disorders.

Why you should stop drinking even if alcohol will not harm you personally

Because alcohol is killing the same number of people as COVID each year, I think we should treat it as a similar emergency. A difference is that many (though not all) deaths due to alcohol were caused by someone who chose to begin drinking, while each COVID victim did not choose to get COVID. I think that there is a moral difference between the two, but not so much that we should “live and let live” and accept the number of alcohol deaths. In this section, I’ll give some arguments for why we have an ethical obligation to denormalize alcohol rather than taking a live and let live attitude to other people drinking.

Most of the time, people behave in patterns they learned from the culture around them. Almost all of my behavior and what I consider normal was learned and copied from the example people around me set. It is very hard to step back from your social context and modify your behavior. In some sense, each individual drinker is choosing to drink, but in another sense, they are each doing what we all do most of the time: following the example of the culture around them. There have been some studies on how much of an effect the general social environment of drinking has on people, and it seems to be quite a lot. This study suggests that the social example of other people accounts for a sizable amount of each drinker’s alcohol consumption:

How malleable is alcohol consumption? Specifically, how much is alcohol consumption driven by the current environment versus individual characteristics? To answer this question, we analyze changes in alcohol purchases when consumers move from one state to another in the United States. We find that if a household moves to a state with a higher (lower) average alcohol purchases than the origin state, the household is likely to increase (decrease) its alcohol purchases right after the move. The current environment explains about two-thirds of the differences in alcohol purchases. The adjustment takes place both on the extensive and intensive margins.

We can compare the normalization of alcohol to the normalization of other behaviors. During the pandemic, part of the reason I was wearing a mask and socially distancing was to set an example for other people. If I lived in an area where no one was wearing a mask or distancing, it would have felt more difficult to choose to wear a mask and distance. Even though each person was individually choosing to mask and distance, our collective choices had a strong effect. We understood that we had a responsibility to normalize a specific behavior to keep everyone safe, even though each person was ultimately responsible for their own actions. I argue that we have the same responsibility with alcohol.

We can think of ideas and behaviors as spreadable in the same way diseases are spreadable. Before vaccines, we understood that we each had a responsibility to be extremely careful about not spreading COVID, to the point of going months without meeting people indoors. The idea that “it is normal and good to consume alcohol” is harming more people each year than COVID did, and it takes much less of a sacrifice to avoid spreading the idea than it takes to avoid spreading COVID.

I don’t think it is much worse to be murdered than it is to die of a harmful highly addictive personal habit. You are a victim of outside forces in both cases. The fact that alcoholics are mainly harming themselves rather than being harmed by other people bears little moral weight for me. In both cases, they deserve a culture that protects them. Denormalizing drinking is one way we can protect them.

1 person dies from alcohol each year for every 1900 people who drink. This means that throughout a lifetime of drinking (let’s say from 20 to 70) 1 person dies from alcohol for every 38 people who regularly drink. We can think of the 38 people as each casting a vote to normalize alcohol and fund the alcohol industry. Because it takes so few votes for an additional person to die, I do not want to be part of that 38.

60% of alcohol is sold to the top 10% of drinkers, who drink an average of 74 drinks per week. This number is misleading and skewed by the top 1% of drinkers, who drink much more than the top 10%, but the fact remains that the majority of drinks are sold to the tiny minority who consume them the most. When you step into a liquor store, the majority of the alcohol you see will likely be sold to people whose health it’s significantly harming, some of whom are addicted to it. When you pay for alcohol, you’re paying a business that is being significantly funded by addicts of the substance it’s selling. You’re helping it stay in business and grow.

I have a special responsibility as someone who is not genetically predisposed to alcoholism to avoid normalizing behaviors that would ruin the lives of people who are not as lucky, in the same way, that we have a responsibility to donate resources to people who were not given as many opportunities as we were.

In elite culture (which in many ways I consider myself a member of) there are sometimes disturbing status rituals where you engage in more dangerous behavior to demonstrate that you’re strong and rich and able to bounce back. There’s pressure to do more intense drugs and to drink more heavily. It’s hard not to see this as a way of filtering out people perceived as unfit or weak. While most people I know do not participate in this, I have been in social spaces where these rituals happen. They’re a form of social Darwinism and I don’t want anything to do with them. Concern about alcoholism is sometimes seen as an implicit weakness, and more people not drinking and raising concern about alcoholism can make it socially easier for even more people to avoid alcohol.

Alcohol is so normalized that most people have no reaction to negative statistics about it. It’s culturally understood that alcohol causes problems, so it’s easier to ignore how harmful it is. If alcohol were anything else and had the same negative consequences, it would be clear that we should not participate in it. If Minecraft were killing 140,000 Americans every year, and if 40% of intimate partner violence occurred after the perpetrator was playing Minecraft, I would not buy or play it. Like alcohol, Minecraft is very fun, but it would not be worth it for me even if I knew it would never personally harm me, because it was having so many negative effects on other people. I would not want to financially support it or normalize playing it.

I can’t think of another activity that’s both as dangerous as alcohol and as normalized. Smoking is more dangerous but much more frowned upon. Driving is more normalized but less dangerous.

Because so many people are being harmed by alcohol, even very small changes in drinking habits can lead to lots of lives being saved. This 2015 study suggests that an alcohol tax that raises the price of alcohol by 10% would save between 2000–6000 American lives per year. If a six-pack of Bud Light costing $0.50 more would save the same number of Americans every year as the number who died on 9/11, it seems clear that individuals setting an example for their peers can also have an outsized influence on the number of people harmed.

It will always be unclear how much effect the example we set can have, but I think it’s higher than we assume. We are highly influenced by the lifestyles of the people we’re closest with. If the 5 closest people in your life were heavy drinkers, you would probably have a very different relationship with alcohol than if your 5 closest people did not drink. Change in behavior of one person in a social group can have unexpected effects, especially if that person is well-respected and clear about why they decided to not drink.

Conclusion

In the past, I’ve been greatly benefited by alcohol. Being drunk sometimes left me so happy that I lingered in a more positive emotional state for weeks after. I take the social benefits of alcohol seriously, but I don’t think they’re worth the cost of so many vulnerable people being harmed and killed, and life without alcohol is just as exciting and fun for me. I understand that for many people giving it up would be more of a sacrifice, but it seems clear that the sacrifice is worth it to protect the people alcohol would otherwise kill and harm.

I do think you, if anything, understate what proportion of the harm is done by that top 1%, it's really the vast majority. That 1% also tends to be poor and dysfunctional, which is why alcohol taxes are so good. Specifically, we want a tax *per unit* of alcohol, to discourage the very heavy drinkers.

This concentration of damages in the most dysfunctional members of society also, therefore, overstates how much social influence anyone reading this piece is likely to have. The local drunks in the park do not give a damn about my values or my example, because I'm not in their reference set.

This is importantly different than the example of meat, where

1) Each incremental meat purchase is clearly harmful

2) There are meat eaters in my social circle who are influenced by my example

3) The vast majority of meat eaters eat meat from factory farms (so are in the 'problematic' category that only a small minority of drinkers are in).

I think you’re ignoring or dismissive of the benefits of alcohol, which may be quite large.

In personal relationships, alcohol does a great deal to relax people and lower boundaries. This is often very positive, leading to friendship, romance, and generally having a good time. You could argue that we should be able to get by without that liquid encouragement, but it is baked into our culture and there is no ready replacement.

At work, drinking similarly lowers inhibitions and allows coworkers and bosses to open up in a way that they simply would not otherwise. Again, ideally we would not need this, but in practice the best way to get the real scoop on what people at your company think is to share a few drinks and spill some tea together.