Data centers & electricity - part 1: they're not raising national prices

Yet, anyway, but they have raised local costs a bit

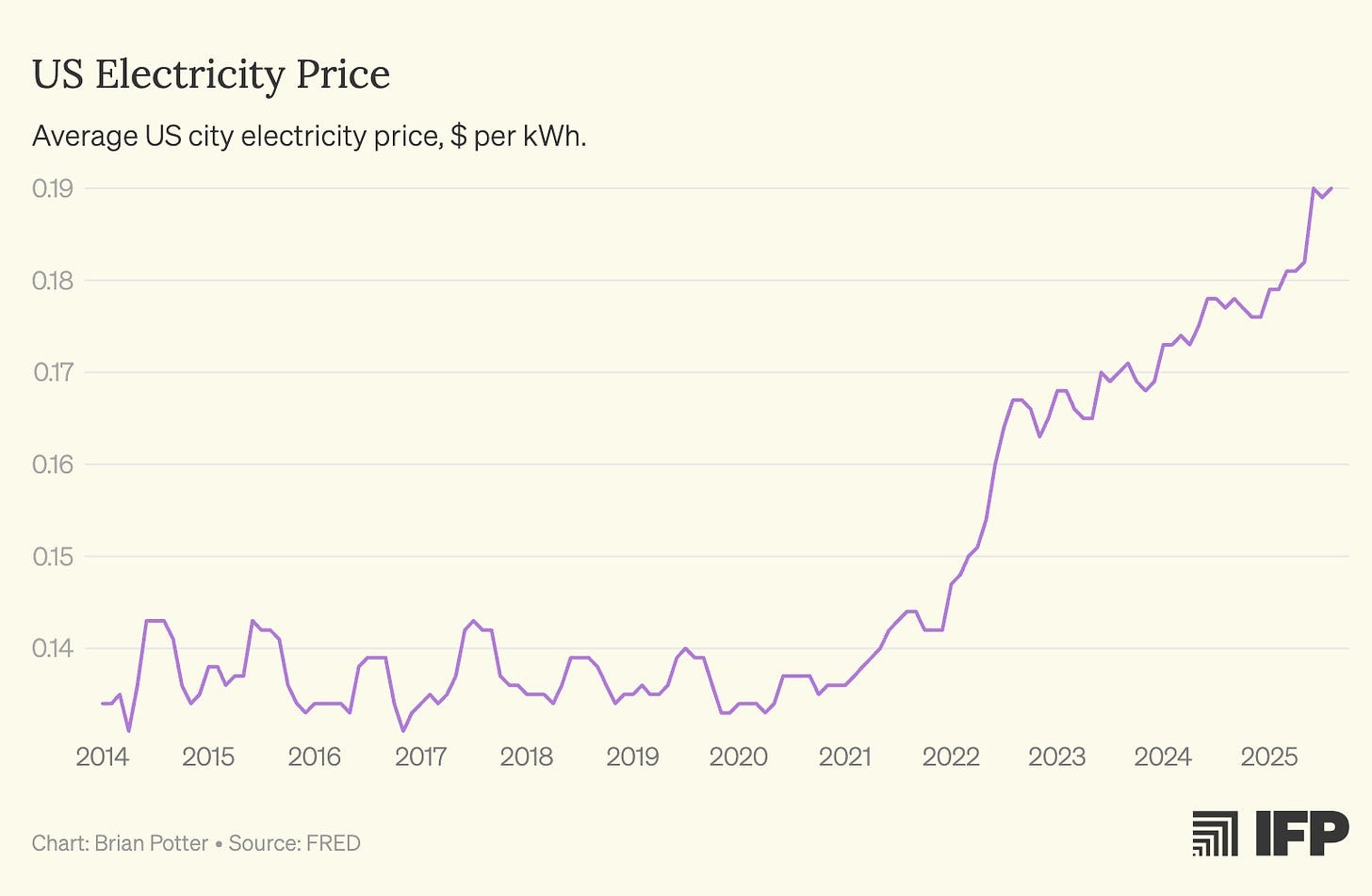

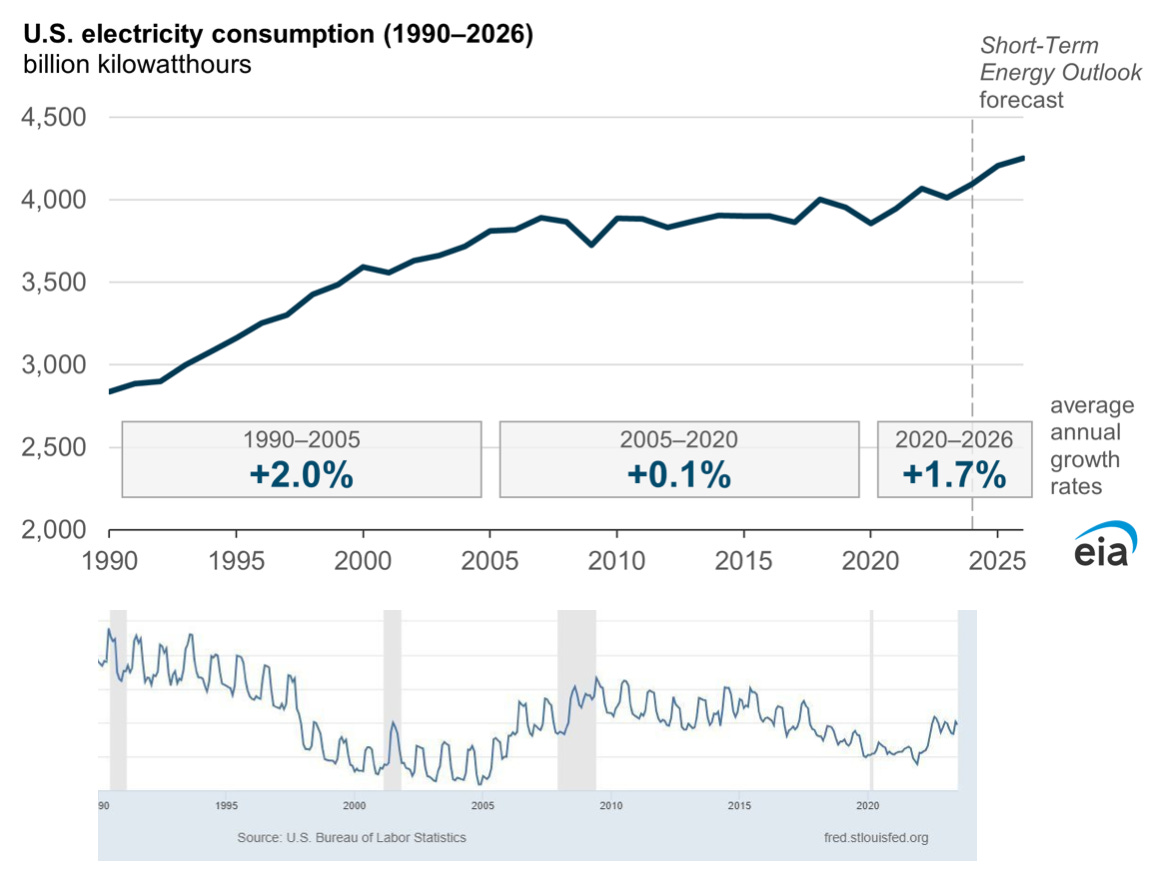

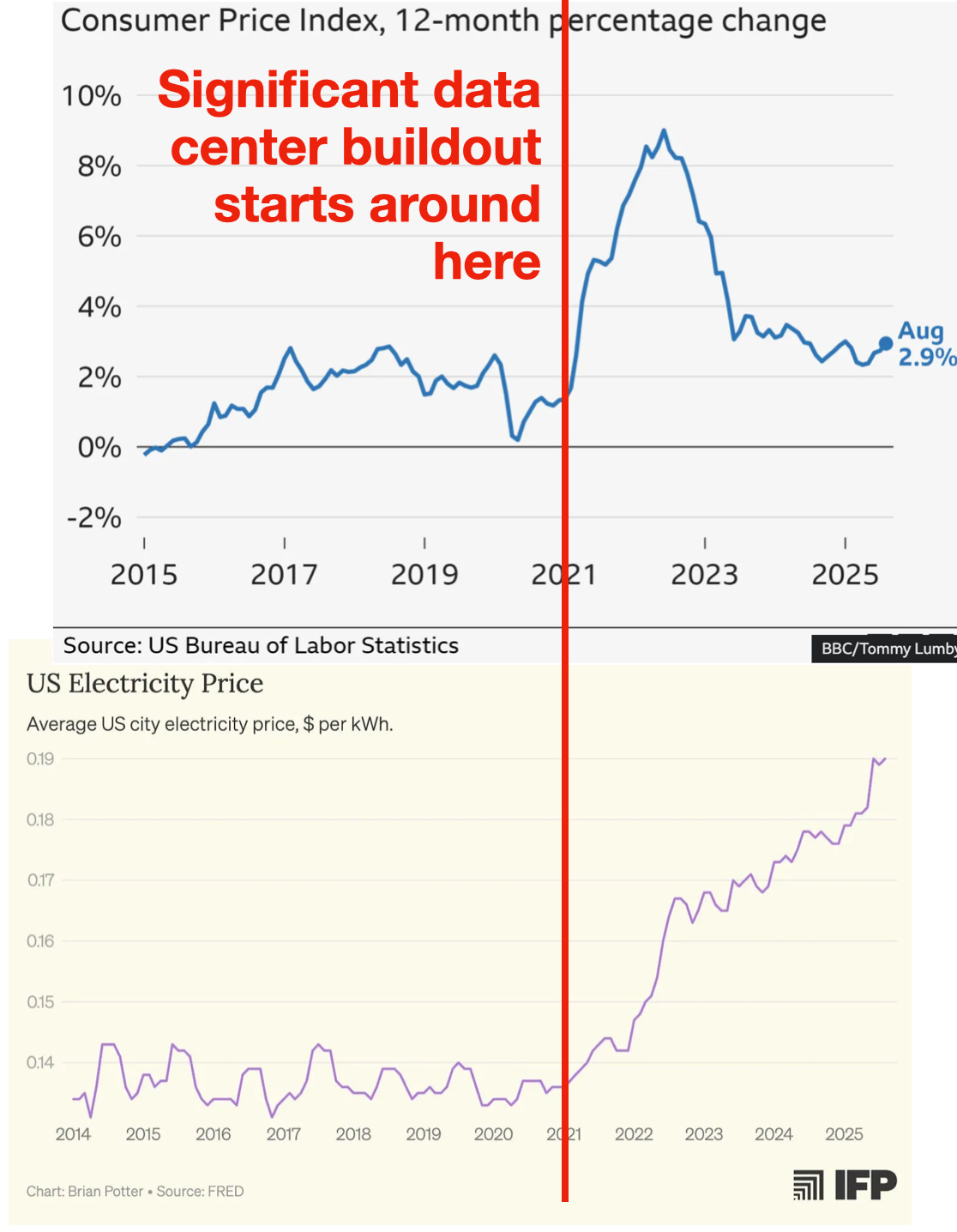

Since 2020, average American household electricity prices have risen 35%.

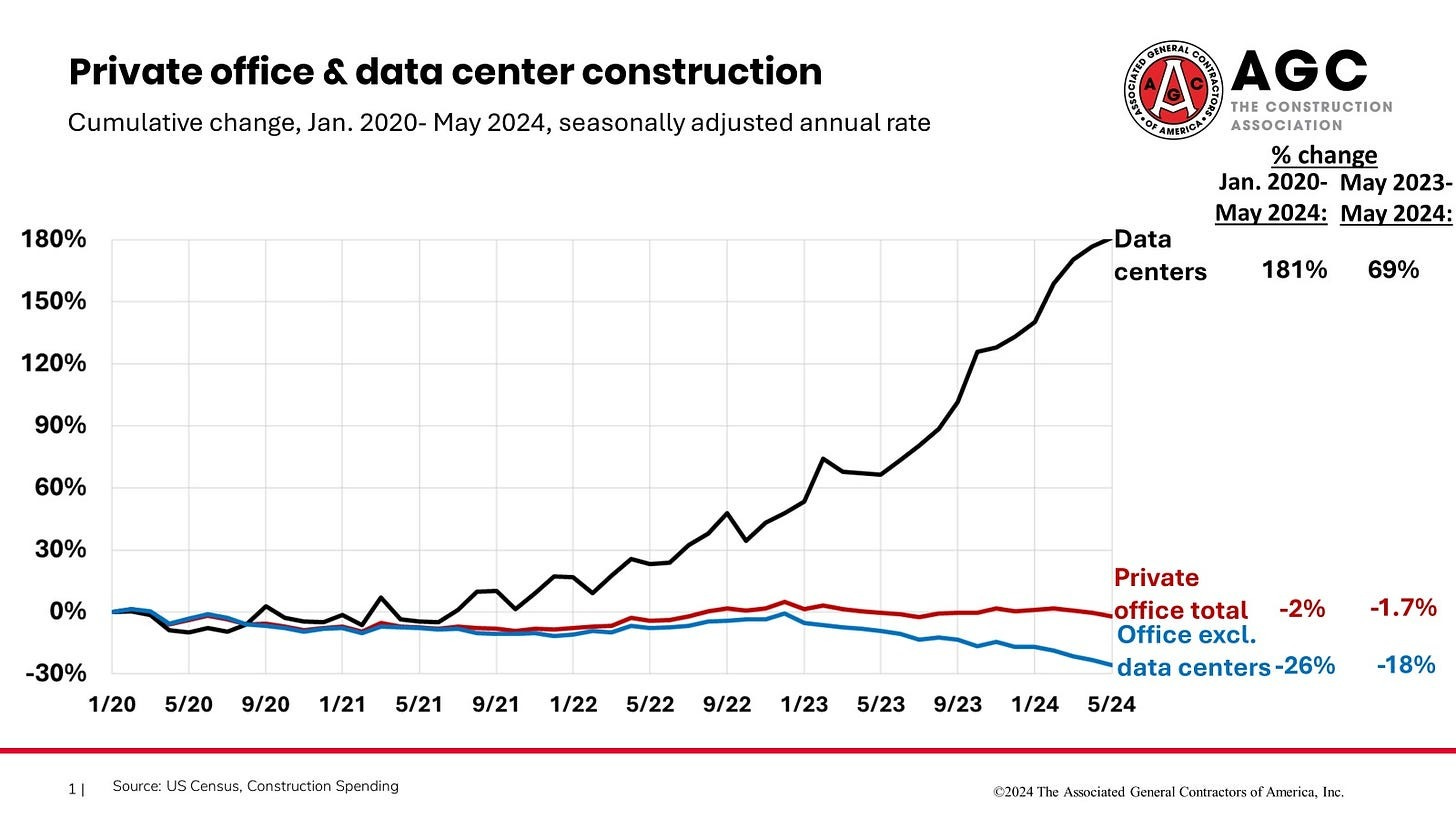

This jump correlates with the massive new data center buildout, which started around 2021. This has led many to conclude that data centers are the main culprit. If data centers raised electricity bills by 35%, that seems like a huge disaster!

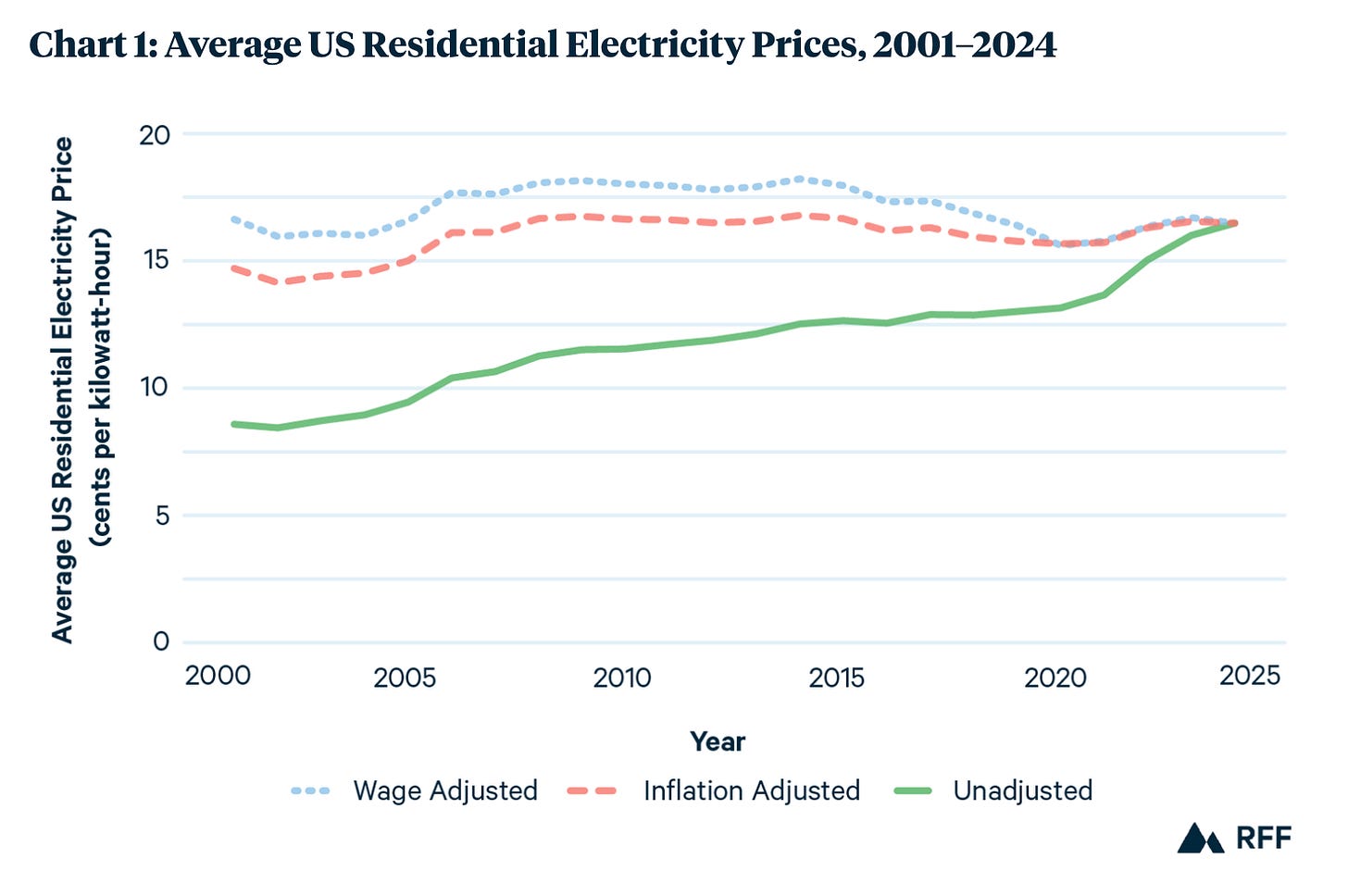

But that’s wrong. If you adjust for inflation, American household electricity costs are still historically low, and have only rebounded to where they were in 2017:

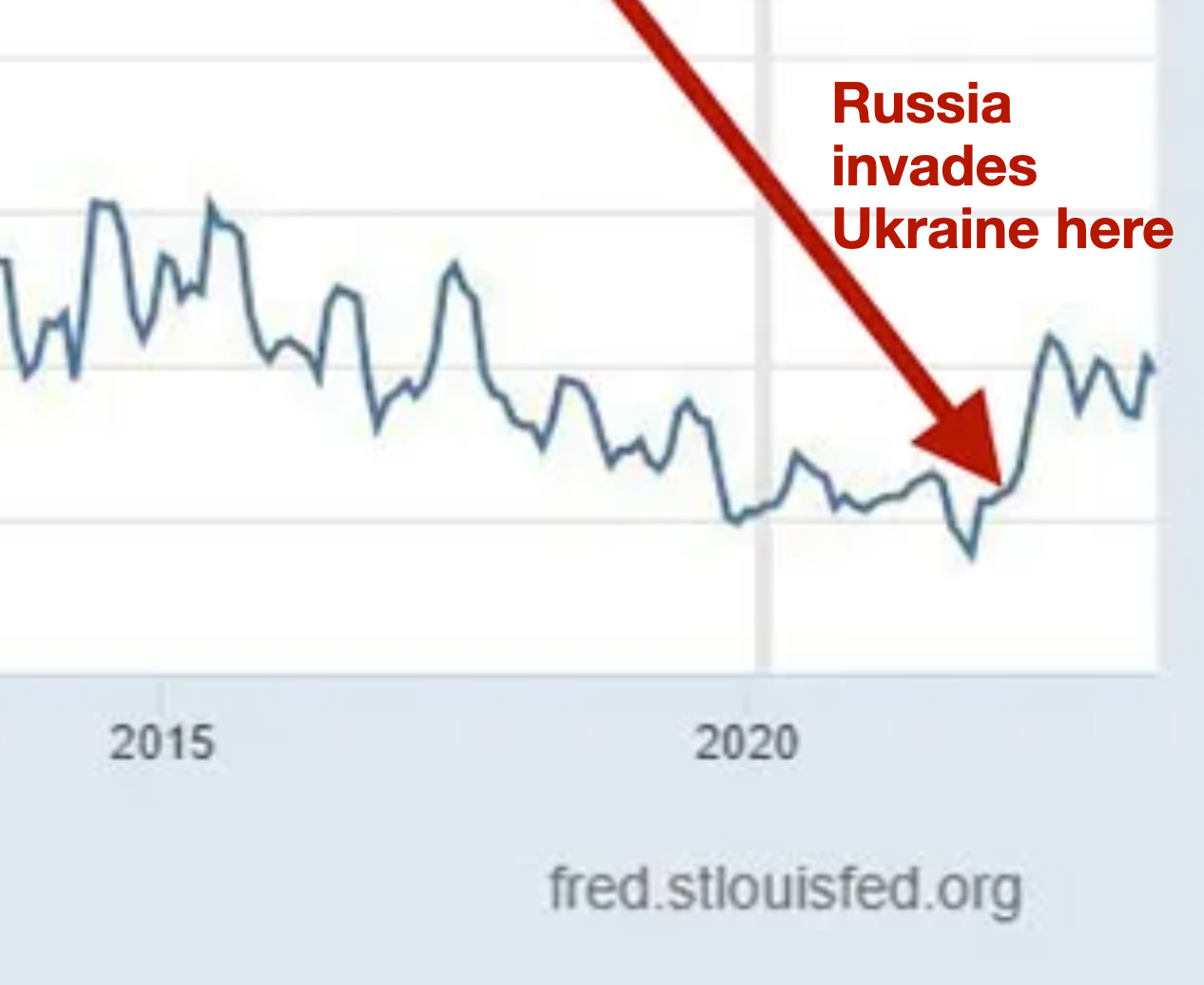

Sometime around 2022, American electricity prices started to outpace inflation. Before 2022, electricity prices closely tracked inflation. After 2022, they went ahead of it a bit.

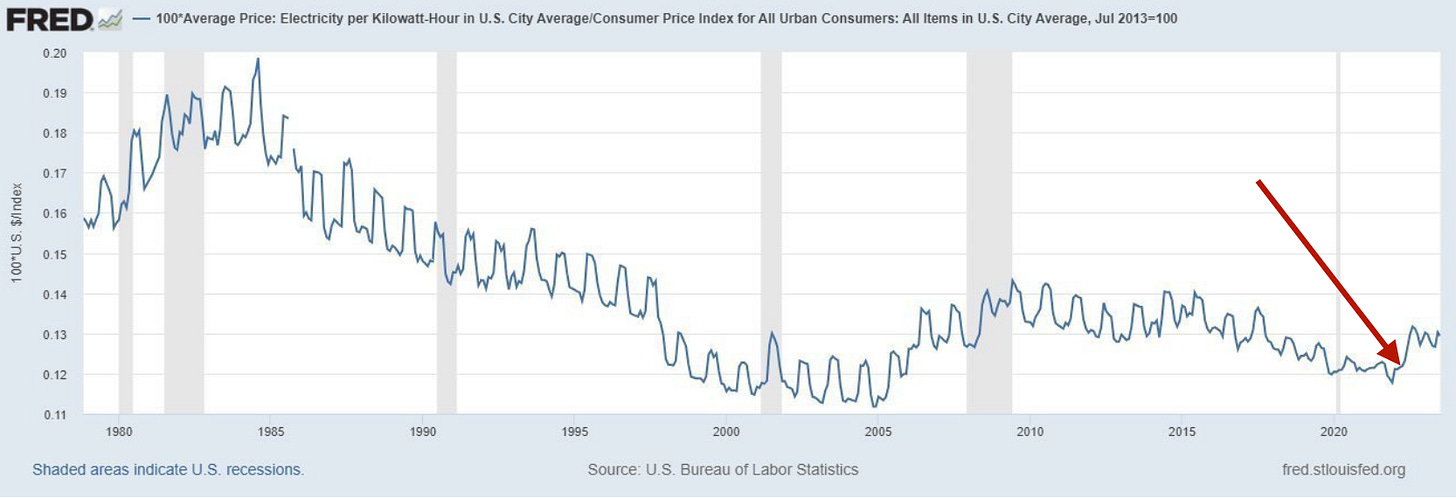

Here’s a broader picture of inflation-adjusted household electricity rates over time. The recent spike begins in 2022, it’s this spike the red arrow’s pointing at that needs an explanation.

Did data centers cause that jump? No. The Lawrence Berkeley Laboratory found that data center activity has not contributed to changes in national average household electricity costs. They specifically mention data centers as one of the things that are not affecting national average inflation-adjusted electricity prices. To summarize their explanation of the price increase:

Prices rose mainly because utility costs rose. On a nominal basis, the average retail price increased about four point eight percent per year from 2019 to 2023. After inflation, the national average was mostly flat over that window, though residential prices climbed faster than inflation.

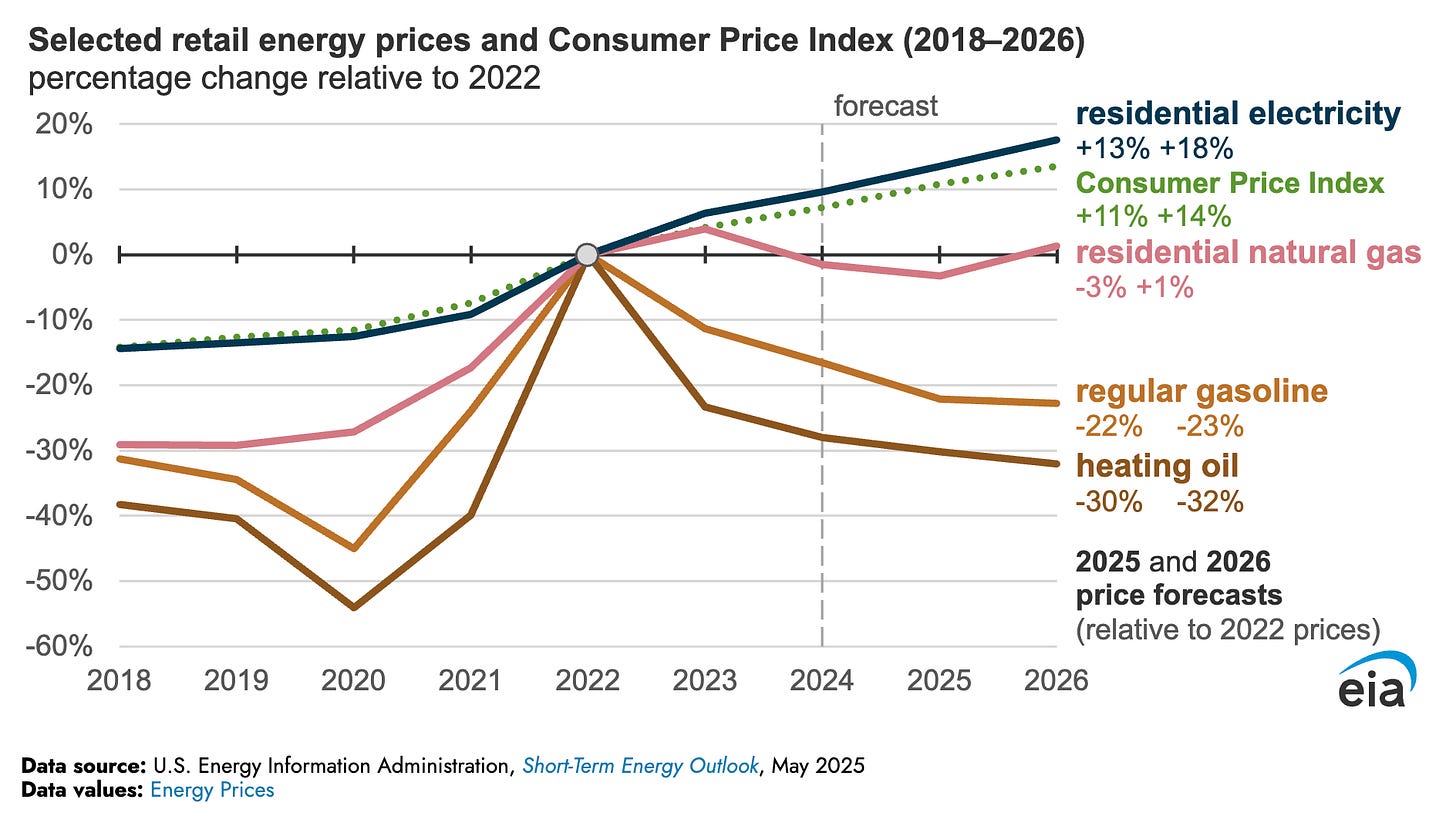

Fuel and purchased power costs were the single biggest mover. Utilities’ fuel and purchased power costs surged in step with the natural gas spike, accounting for about half of the total expense increase. Gas prices then eased, but fuel and purchased power costs in 2023 were still about thirty percent above 2019.

The rest of the cost growth came from operations and maintenance, depreciation, taxes, and other line items.

This explains why the jump happens when it did: Russia invaded Ukraine, Europe stopped buying Russian gas, America was suddenly competing with European countries more for natural gas from other places, and natural gas prices spiked for a bit. Here’s a graph of natural gas prices:

That red arrow I added to the graph of electricity prices is on the day when Russia invaded Ukraine.

There are a few additional reasons to think data centers didn’t cause this spike.

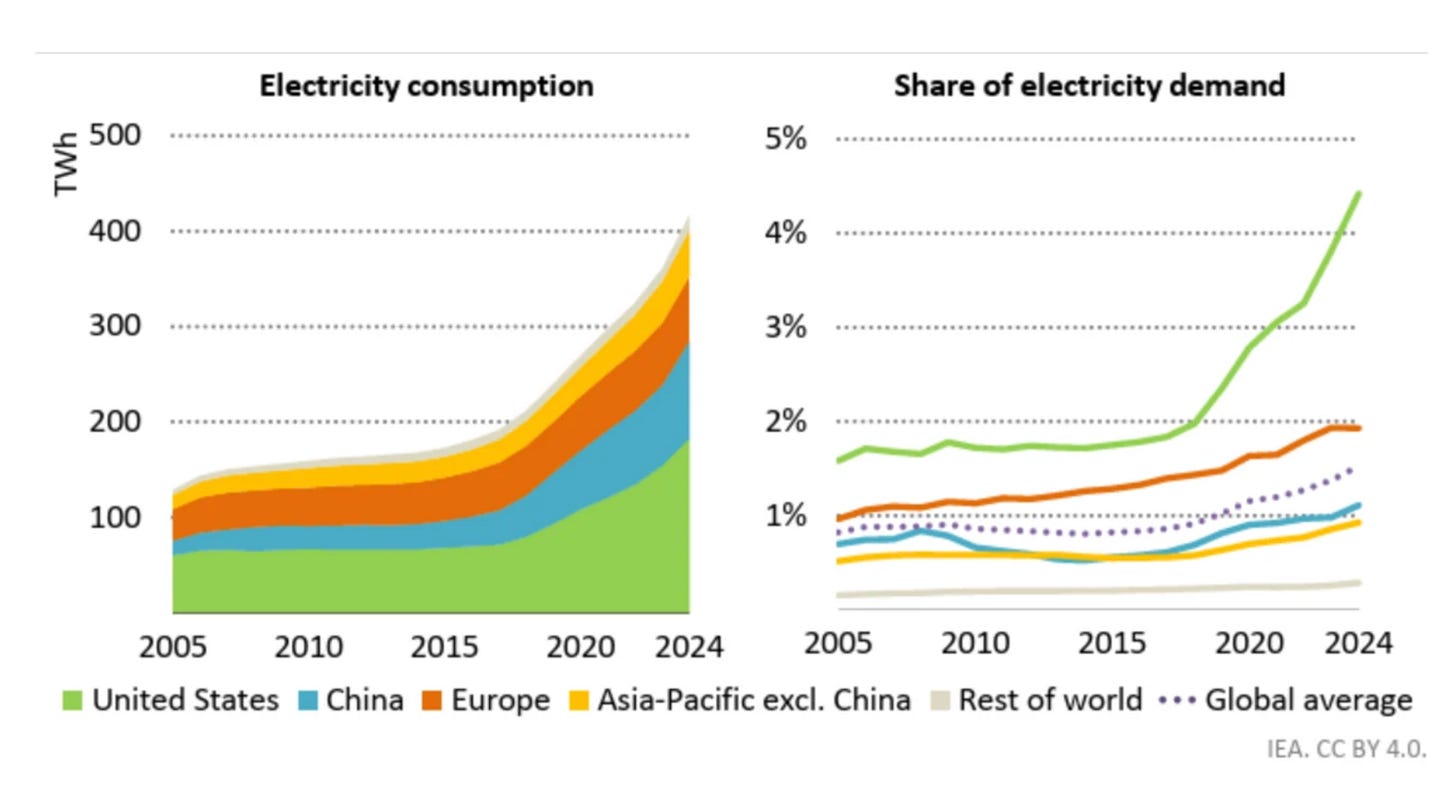

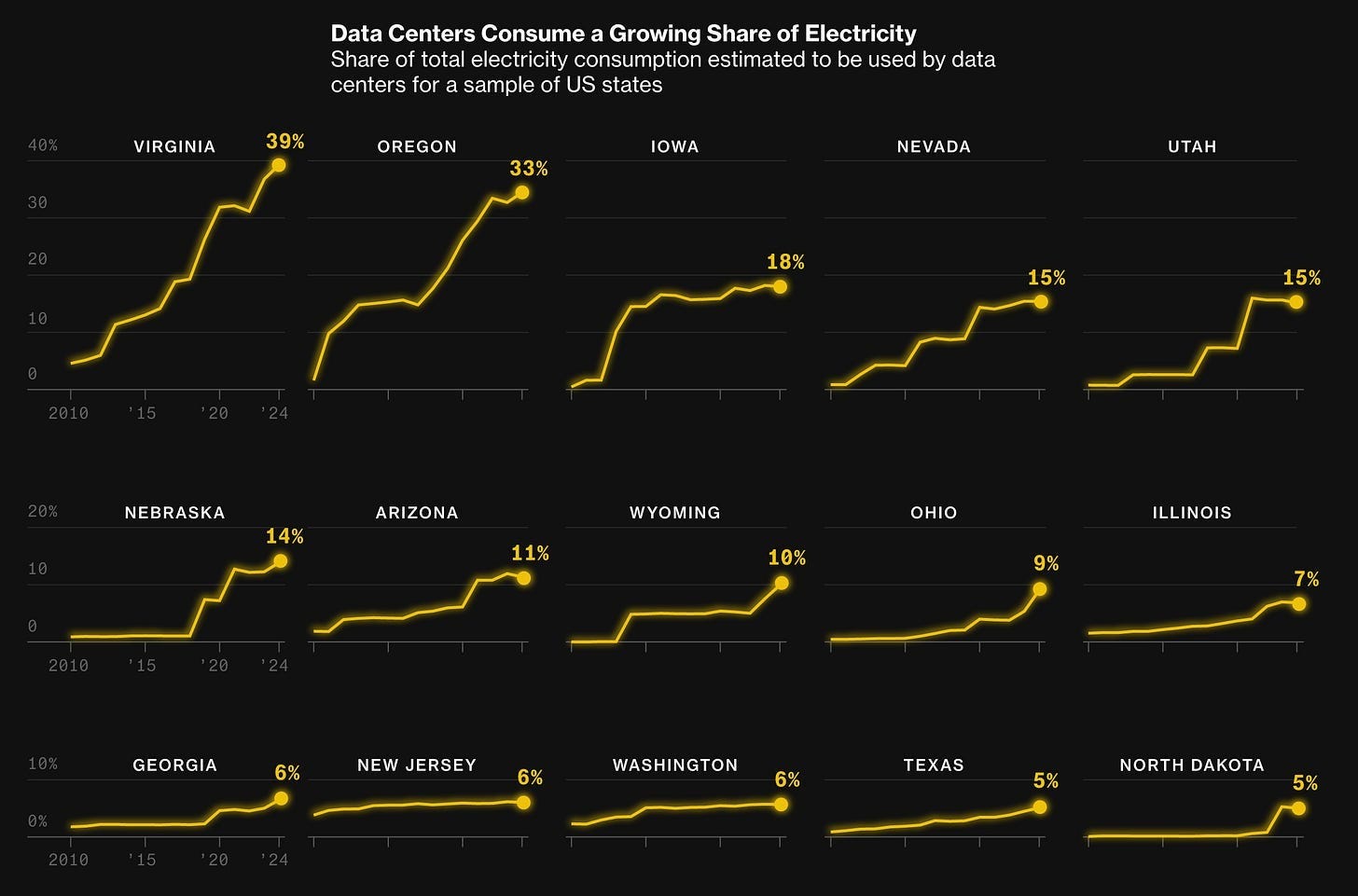

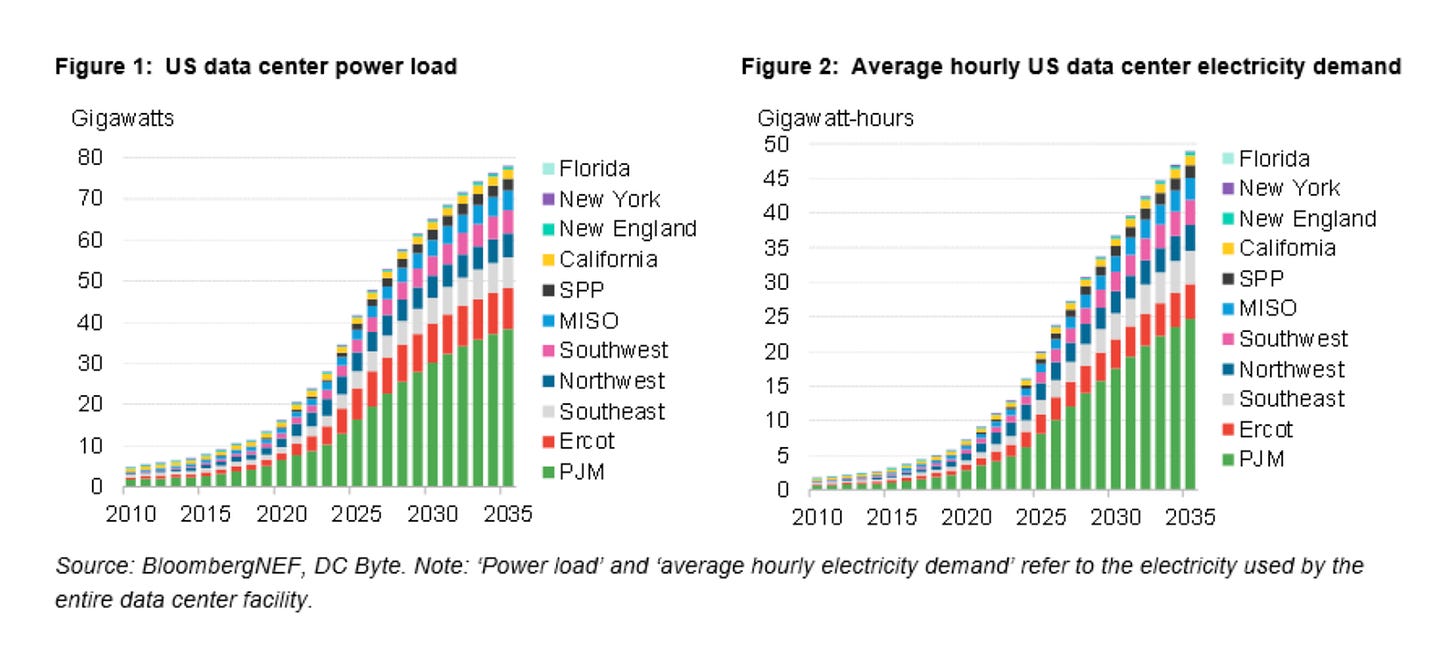

First, the rise in data center electricity demand in the US started a few years before the spike. It’s a pretty straight line up, and markets have a lot of heads-up when a new large buyer like a data center is coming online. It would be weird if halfway along this basically straight line in 2022, energy markets were suddenly taken by surprise:

Second, American electricity demand is rising for the first time since 2007 or so (with data centers responsible for about 40% of the growth), but it’s still rising at a slower rate than it had for most of the 20th Century. Total electricity consumption is driven by demand, so a consumption graph is a good proxy for a demand graph. Importantly, during the period from 1985 to 2005, we sustained a higher rate of increasing electricity demand, but inflation-adjusted household electricity prices fell the entire time.

So it’s possible in principle anyway for electricity supply to keep up with demand and keep prices low, for the same reason a grocery store doesn’t double its prices when it opens a second location. Notice that there was a period from 2020 to 2022 when electricity demand was rising but prices were flat. Another hint that this is more of a problem with supply.

This is the first conclusion of my deep dive: Data centers have (so far) not affected national average household electricity bills. Many of the graphs that get shared about this are showing the effects of inflation, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and a series of other supply-side issues with normal electricity costs that aren’t the result of responding to rising demand.

This is not to say that data centers won’t affect national prices in the future. Just that as of 2025, the average American’s electricity bill has not increased as a result of data center demand.

Brian Potter concluded his excellent deep dive on US electricity prices by noting:

At a high level, trends in wholesale electricity prices seem to mostly match trends we see in consumer prices. Until 2020, wholesale prices were flat or declining; since 2020, they’ve risen substantially, faster than consumer electricity prices. And in most places, transmission capacity appears to be an increasing bottleneck: we’re having a harder and harder time accessing the least expensive power. Probing the specific relationship between wholesale electricity and consumer electricity prices would be complex, and beyond the scope of this essay, but it seems likely to me that rising wholesale prices are a major factor.

The main question left to answer is how data centers affect electric state and local bills electric rates, not national rates.

Unfortunately, locals who live near data centers can’t tell what portions of their electric bill increases were caused by inflation, Russia, or supply-side issues, and what was caused by data centers. The data center buildout started in 2021, at the exact same time American inflation began to skyrocket.

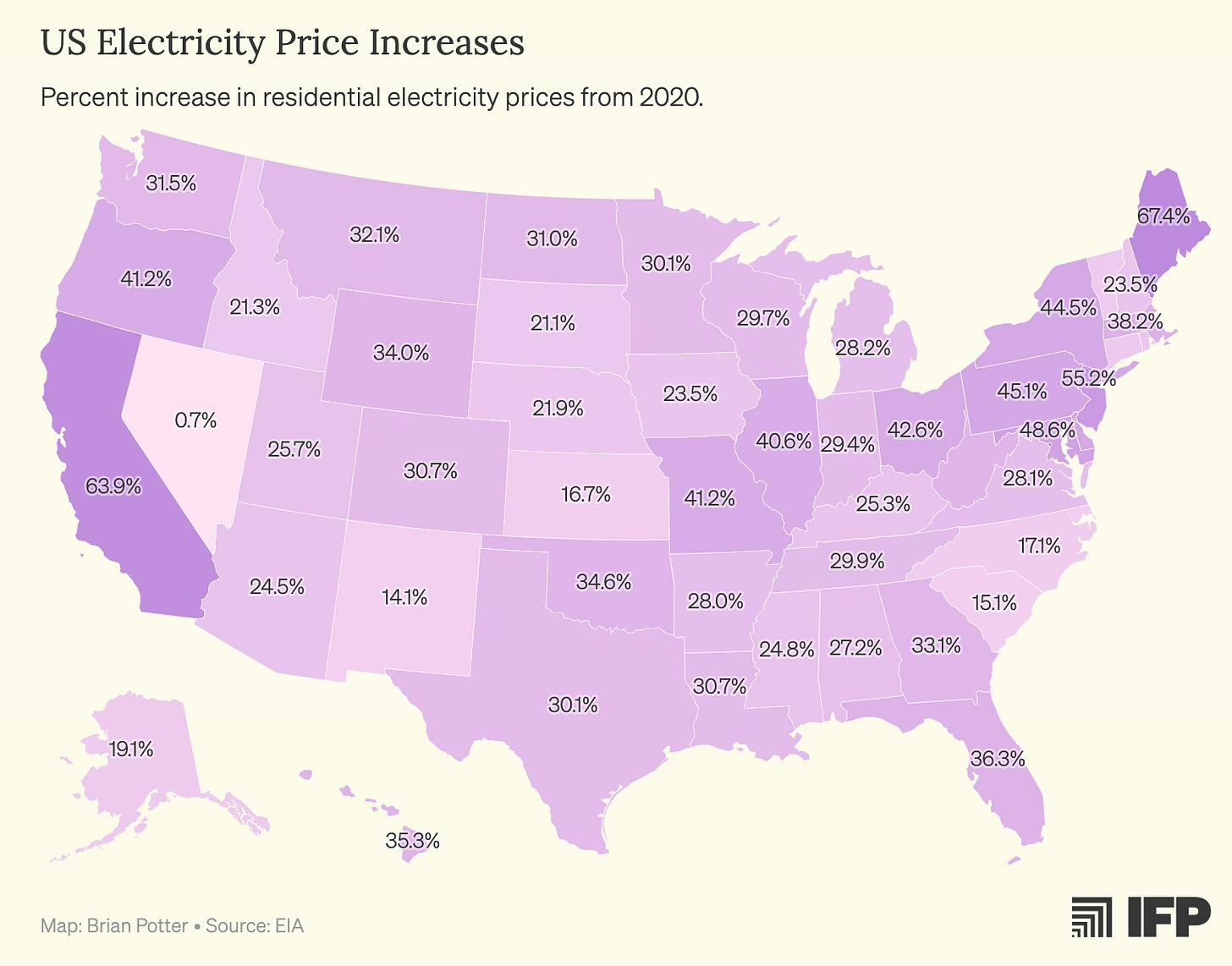

Between 2020 and 2025, the average Virginia resident’s electricity rate went up by 28.1%. Virginia has both the highest percentage of electricity used by data centers, and some of the fastest data center growth in the country.

If you were a resident of Virginia, you might look around, notice that data centers in your state are using 33% more electricity than they were 5 years ago, and that your electric bill went up by 28.1%. You might conclude that there was a connection, and even go on a More Perfect Union video to talk about how data centers raised your electricity prices.

But you might not know that most of that 28.1% growth was due to inflation, or more importantly that Virginia’s electricity prices actually increased less than the national average:

Most American states don’t have anywhere near as many new data centers coming online as Virginia. Maine barely has any, but its rates shot up faster than any other state. If data centers were having a really massive impact on electrical bills, wouldn’t you expect your bill to grow faster than states without data centers?

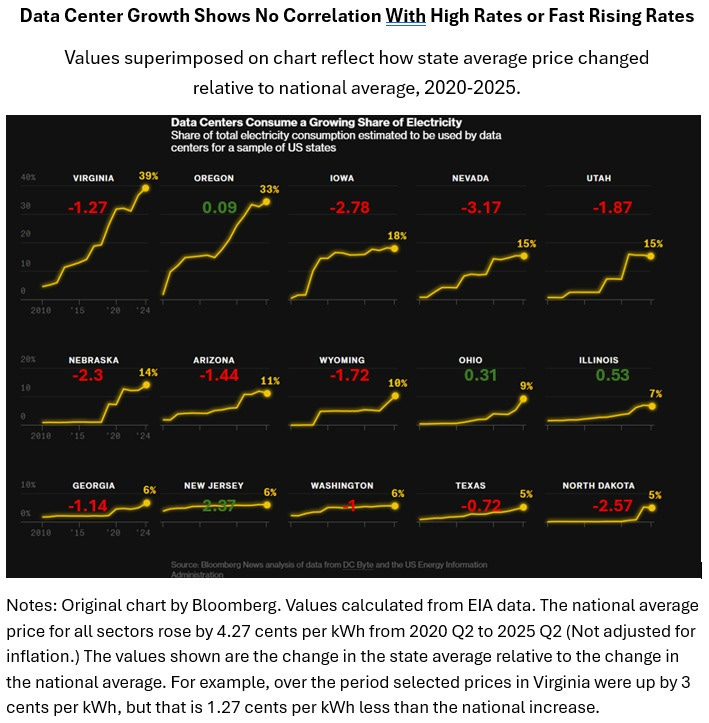

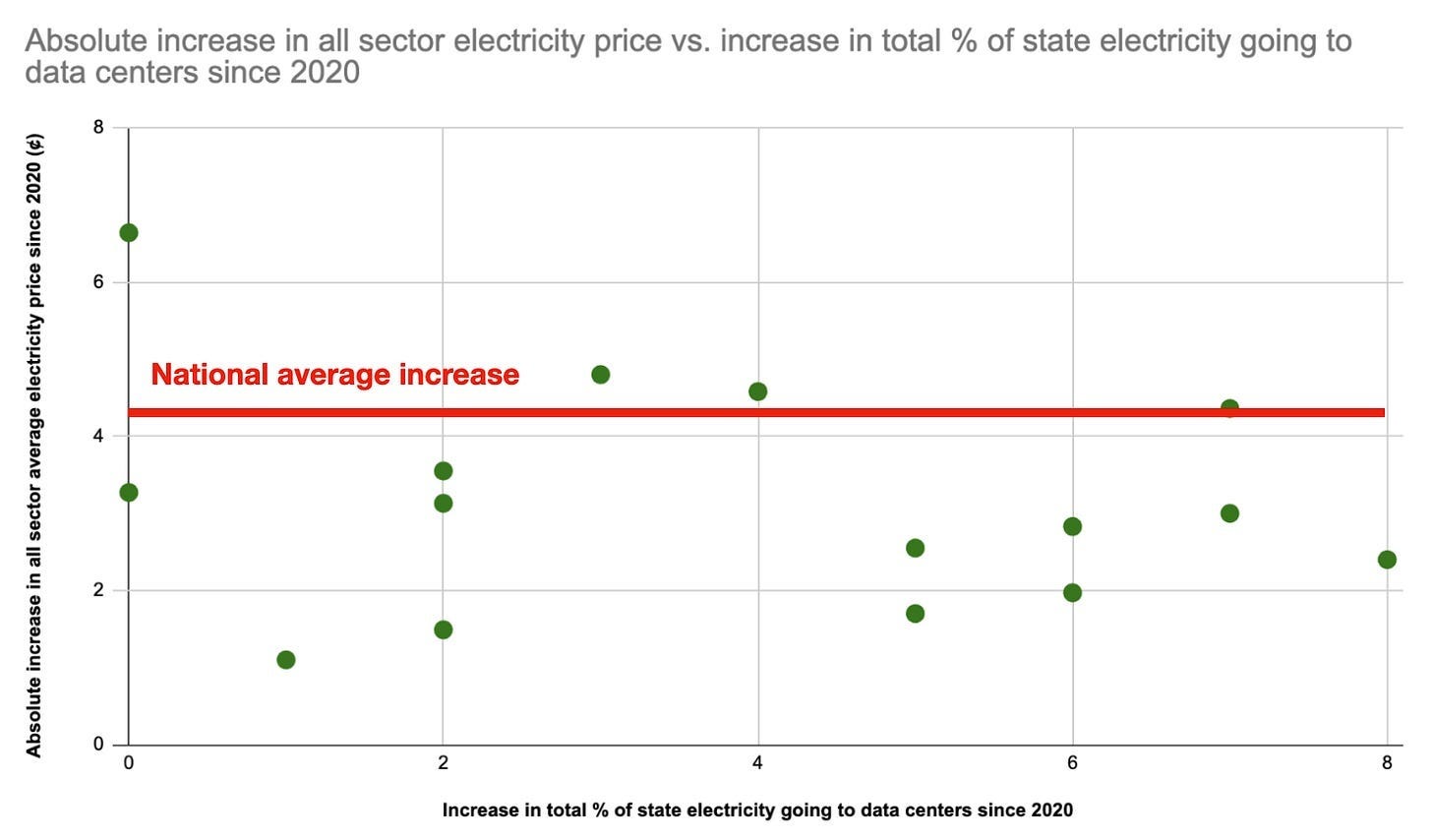

Maybe Virginia’s a fluke, and the other states with huge data center builds have seen skyrocketing electric rates. Michael Giberson at RSA looked into this. The national average electricity price increase for all sectors was $4.27. He looked at each state with the most electricity going to data centers and added numbers to the graph to show how state prices grew more (green) or less (red) than the national average of +4.27 cents per kWh.

11 out of 15 of the states with the most data center buildouts have seen lower than average increases in electricity rates. Further, the red numbers are all way larger here than the green numbers (except New Jersey). Even the states that grew more than average were basically right at the average line. Weird! Here are these numbers on a graph:

So far, this does not look like data centers are uniquely disastrous for electricity bills.

But things get murkier. 30-60% of a data center’s operating costs are its electricity bills. This means data center companies mostly opt for states where electricity costs are low and there’s a lot of pre-existing grid capacity. These cheap, abundant grids can handle massive new loads, but this does not mean prices don’t rise at all as a result of data centers, they just may rise less than if data centers had built elsewhere. Companies have an incentive to build where they will raise electricity costs the least, that’s where they’ll also be paying the least for electricity! So this leaves us with an unfortunate paradox where data centers may be raising local prices, but they’re often in the places we can detect that the least. Also, there might be very local effects that don’t show up at the state leve.

We know shockingly little about exactly how much data centers are affecting household electricity prices at the state and local level. We do know they have made household electricity somewhat more expensive than it would have otherwise been in specific locations, because they have been cited by authorities in Virginia, Arizona, Delaware, Oregon, and other places as one of several causes of rising costs.

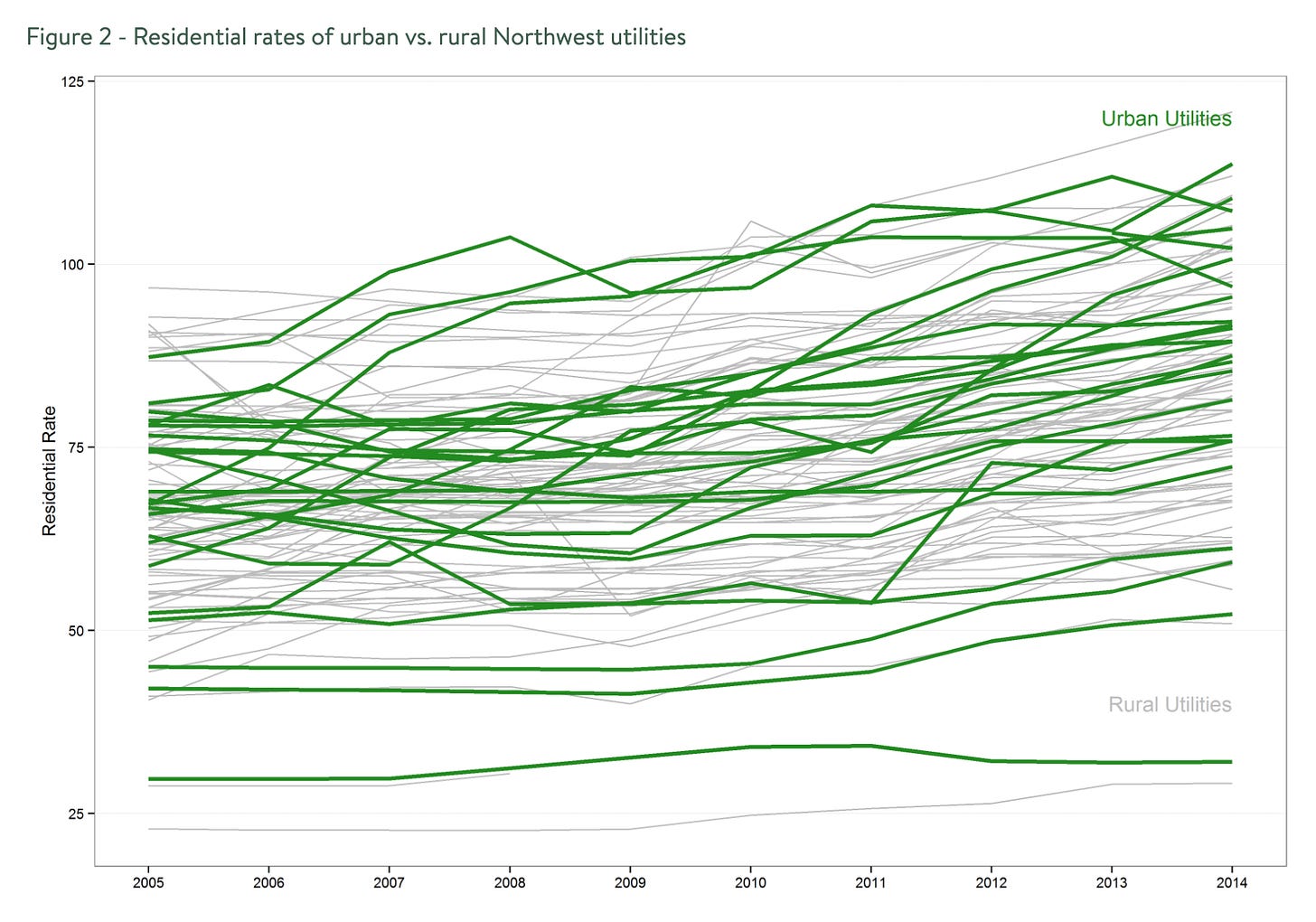

Complicating all this still is that there is no clear longterm correlation between how much total electricity is used in your area and your electric bills, for the same reason larger grocery stores don’t necessarily charge higher prices. Once supply catches up to demand, prices balance. If higher local electricity demand led to permanent higher prices, we would expect urban electricity prices to be higher than rural ones. In reality, urban and rural rates are basically the same.

Something odd in the debate is that some people are implying that data centers are making electric prices permanently higher by drawing more power. This is obviously not how electricity markets work. The thing that spikes your electricity bill is demand outpacing supply in the short term, not just a total increase in demand over the long term.

But also, data centers are forecast to just keep being built, so the grid might be in a permanent state of catch-up for a while, keeping prices higher before they have a chance to adjust.

And all this is in the background of America needing to do a huge buildout of clean energy to transition away from fossil fuels, and all that infrastructure would cost consumers more anyway. Also, whose responsibility is it to keep rates low? The private consumers of electricity, or the utilities? Does it make sense to both say that the utility’s responsible for keeping rates low but also there’s just not enough capacity to do that in the short term so regardless data centers will raise costs a bit? Maybe we could redistribute all that tax money data centers provide to pay for consumer electric bills, or… or what about…

Every time I try to address one specific part of this topic, I come away thinking people can only really understand it if they understand five others as well. The complexity builds. I think you can’t really understand the issue of data centers and household electricity costs without also knowing things like:

Data centers bring in more tax revenue per watt-hour than any other industry,

The differences in tax cuts local governments provide them to entice them to build there

How this all really depends on whether the local grid can build out enough new clean electricity infrastructure.

How to think about who’s responsible for rising prices between consumers or producers.

How data center builds might be good for the green energy transition because they’re forcing these huge new investments in the grid we need to make anyway

How electrifying everything in the economy is a massive project necessary for green energy, so electricity demand is going to rapidly shoot up with or without data centers.

How AI usage is expected to accelerate or harm the green energy transition

and so on.

I decided that I did need some kind of basic understanding of all this stuff, so I set out to gather what I think is the important info here. I’m just a hobbyist and far from an expert on any of this. This series is more a summary of what I’ve learned after doing a bunch of deep dives on these topics rather than “This is the definitive final story of data centers and electricity.” I do think I’ve climbed to reach some vistas in this mess of a problem where I can see things more clearly, so this series will aim to get you there too.

It's going to be a rough time ahead, thanks for clearing the misinformation. Even with it being certain actors here and there, it's all rushing and having the dust settle is calming.

Made an error with Second wind, I meant Second thought, has given mixed claims too, with the same'ish info you refuted. My bad. I guess journalists are going to treat this like catnip for years to come.

This may be repeated by outlets, and the principle of nuance will have to be expressed.

the second to last paragraph is a duplicate