Do data centers only seem bad for the climate because we can see them?

Most of your climate impacts are invisible

One of the most important facts about climate change is that where emissions happen is counter-intuitive, often hidden from us. Using a computer for hours doesn’t add nearly as much to your daily carbon footprint as eating a burger, but the computer feels more energy intensive than your lunch.

The climate does not react to which industry emits or which specific buildings emit. It only reacts to the total CO2 in the air.

The national microwave

If data centers didn’t exist, we would need to rely on our personal computers to run everything we do online. When you logged into YouTube, you’d run YouTube software on your own computer like it was a video game, and save all videos you upload on your own computer. Every time someone else wanted to watch your videos, they would need to connect to your computer like other players on a video game can connect to a game you’re running. The magic of data centers is that by piling huge amounts of computing in one place, you can make all that computing more energy efficient than it would be otherwise, and more accessible for everyone involved.

Other things don’t work this way. If I want to microwave something, I have to own my own microwave. I can’t send things off to some centralized microwave somewhere else.

What if I could?

Let’s say there were a single national microwave. When you needed food heated up, you would teleport the food to the national microwave, in the same way you effectively teleport information from your computer to data centers.

This microwave would need to be massive to fit all microwaved meals Americans are making at any given time.

I estimate that all microwaves in America use ~25 GWh of electricity every day. This means that the big national microwave would be using as much electricity every day as Seattle. An entire new city’s worth of electricity demand added to the grid, just for heating food!

What about the water? Well the average water consumption per kWh in American power plants is 4.35 L, so this microwave would be consuming 110,000,000 liters of water every single day. 45 Olympic pools of water every day.

I think if the big national microwave existed, it would be drawing a lot of scorn. “This seems so wasteful. What’s wrong with just using an oven?” People would see it as sapping a whole city’s worth of energy. There would be articles about how it’s sapping the local grid and using as much energy as 800,000 households.

But this microwave does exist. It’s just hidden, broken up into hundreds of millions of little pieces of itself scattered across America. The impacts are just as real as if it existed in one place. The climate does not care about where emissions happen. It just responds to total emissions. All microwaves in America are emitting just as much as the big national microwave would. But they don’t exist in one place as a single evil building people can get mad at. The big national microwave is invisible.

Suppose someone says “Tech bros just reinvented the oven, only this time it’s destroying the planet.” Would we want people to stop using the big microwave and switch to their ovens?

Well, ovens use way more energy to cook the same food. Getting people to stop using the big microwave and switch to ovens would actually cause way more emissions in total, probably around 10 times as much. Those emissions would just be dispersed across the country, so people would feel better about them, because they couldn’t see them. People really like when they can’t actually see the effects they’re having on the climate, but those effects are still real. Shutting down the big national microwave would be a huge environmental mistake, even though it looks much more evil than everyone’s individual ovens.

These are three mistakes I think people would make if we had the big national microwave:

They would only see it as a single, inert building using a ton of energy, and wouldn’t compare its benefits per unit emissions to other buildings. They wouldn’t consider how many more people were interacting with it, or divide the energy cost by the number of people using it. It would make sense that a building managing all microwave needs for all America would be using more energy than a nearby toy store, because it would be serving a lot more people. The toy store is actually way more inefficient with its energy, but comparing it to the toy store would be ridiculous. If it sounds ridiculous to say “All American microwaves are using more energy than this one toy store, people should all throw away their microwaves!” then it should sound equally ridiculous to condemn the big national microwave for the same reason.

They would want to shut it down and have switch to things that seem more “normal” like using an oven, even though those normal things are mostly way worse for the climate. The normal things don’t have a big evil building of their own to represent how much energy they’re really using, so unlike the microwave, their emissions are invisible, even though they’re much greater in total.

They would only see the building as using a lot of energy relative to everyday people (800,000 households!) and wouldn’t consider it in the context of climate overall and how big of a problem it is compared to most other things we do. They would prioritize optimizing the microwave over much more easy climate wins, like shutting down coal plants or electrifying cars.

People also make these three mistakes when thinking about data centers. When you see climate arguments against data centers, check and see if the same arguments would apply to the national microwave, and wouldn’t apply to regular microwaves. That tells you that the other person is just mad that emissions are visible, not that they’re a lot.

Data centers as the national microwave

Data centers are weird buildings. They concentrate more power demand in a smaller space than basically any other type of building. They also, at any one moment, have hundreds of thousands of people from around the world interacting with them.

From the outside, data centers look boring and inert.

But in some sense they’re the most active physical objects we’ve ever built. They’re building-sized computers constantly running gigantic amounts of equations. Microsoft’s 2023 GPT-4 training cluster reportedly had ~25,000 A100 GPUs in a single build. This amount of chips could perform around 1018 (million trillion) addition or multiplication calculations per second. All humans who have ever lived, doing one calculation per second for 24 hours per day, could together do that many calculations in about 100 days.

Each data center is more of a massive very general tool than a normal building.

Like the national microwave, hundreds of thousands of people interact with a data center at once. People effectively teleport computer tasks away for some far off building to deal with it much more efficiently and reliably. When you read stories about data centers using huge amounts of power, you should think “This is because tens of thousands of people are interacting with the building at once and using it as a tool, like a gigantic national calculator.” You might think the way the data center’s being used is bad or wasteful, but you should still hold in your head that this is just a very very concentrated result of 10s of thousands of small individual decisions, like the microwave is.

Data centers are uniquely energy efficient. Basically all the energy they take in is delivered directly to incredibly optimized computer tasks. They’re the most energy efficient way to do a lot of computing. Since computing can give us valuable information about the world, it seems good to be able to build these huge clusters where computing can happen more efficiently than anywhere else.

Individual data centers can grow so large that they take on the energy demands of whole cities, but globally all data centers on Earth (supporting the entire internet) use 1.5% of global electricity, and only 0.23% of global energy. Data centers are managing and hosting the global internet. The average person on Earth spends 6 hours and 40 minutes every day on the internet, so they’re spending 40% of their waking lives interacting with data centers. Data center efficiency means that something we all spend almost half our lives interacting with only uses 0.23% of our global energy. I’m not aware of any other service that comes close to this.

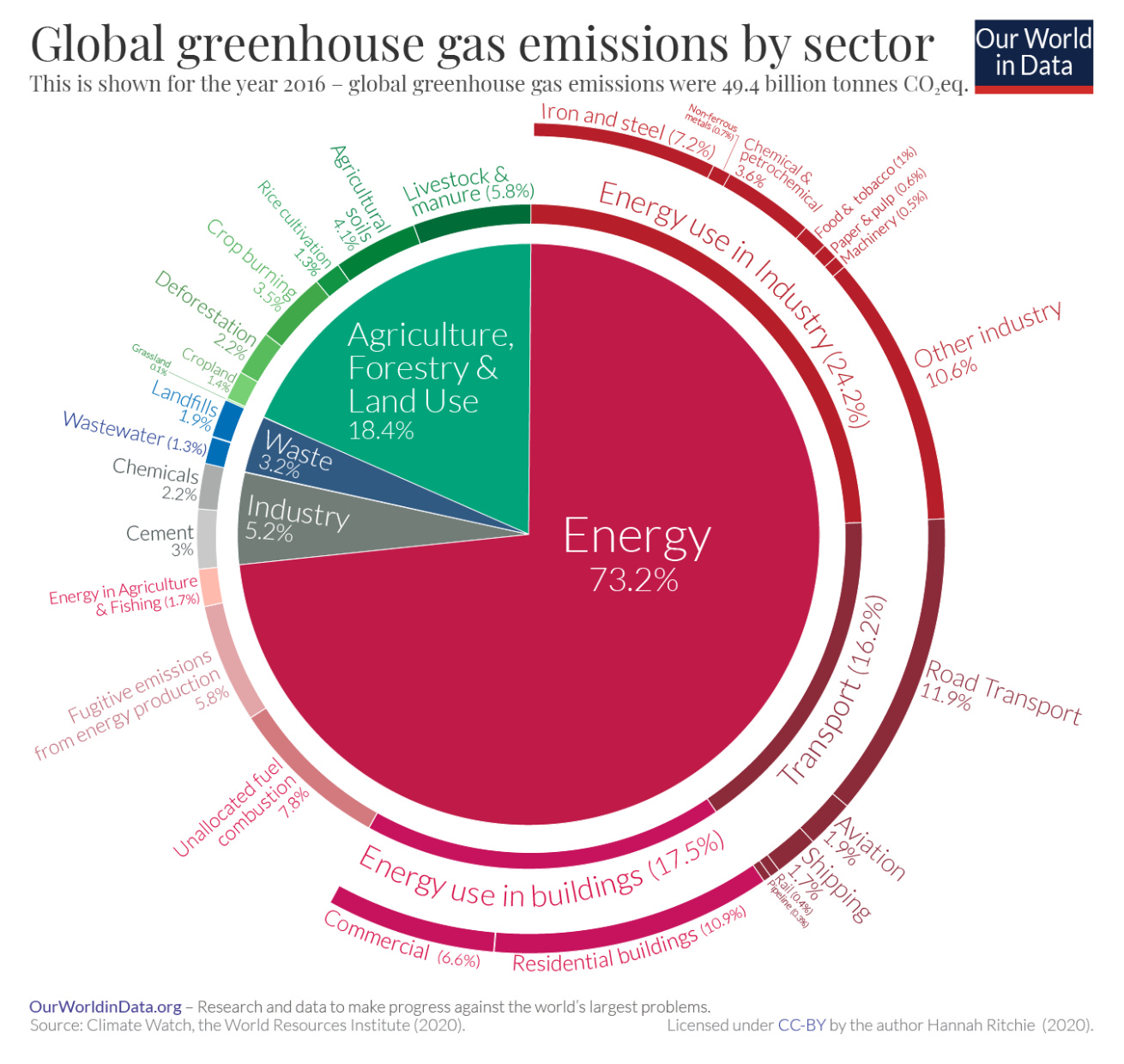

All global data centers were responsible for 0.48% of emissions in 2024. On this chart of where global emissions were happening (in 2016, more recent data’s hard to find) all data centers would be about the size of the “rail” line.

Obviously this is not nothing, but take a minute to look through everything else in the infographic. If you hadn’t heard of data centers before, and saw them listed as a tiny stripe (they would be a small sliver of the “commercial” stripe), would something emitting 0.48% of global emissions stand out to you as something that required special attention? How many conversations in the last year have you seen about the emissions of cement, or landfills, or paper & pulp production?

I think a part of the reason you haven’t seen more discussions of the latter is that they don’t have big evil buildings of their own. There’s no big centralized paper production mill that’s using huge amounts of energy and water people can get mad about, even though paper production overall is emitting significantly more than data centers right now. People are less upset about those emissions because they’re invisible.

Identifying climate bad guys by just looking at what seems like it’s a bad guy is a terrible way to think about the problem. It makes it easy to become tricked by industries hiding or normalizing their emissions.

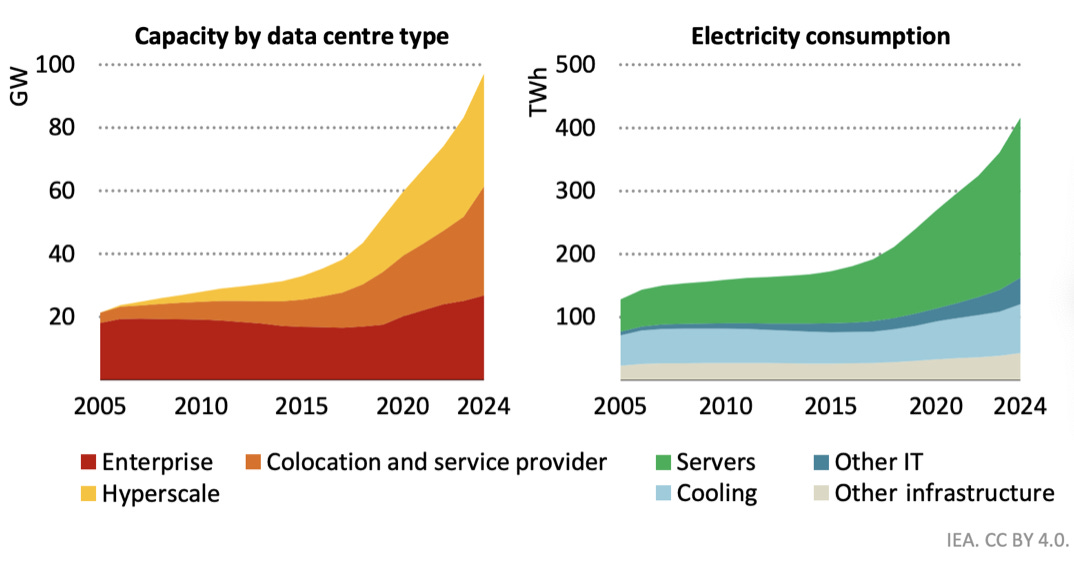

Of course, unlike other industries, data center energy use is growing.

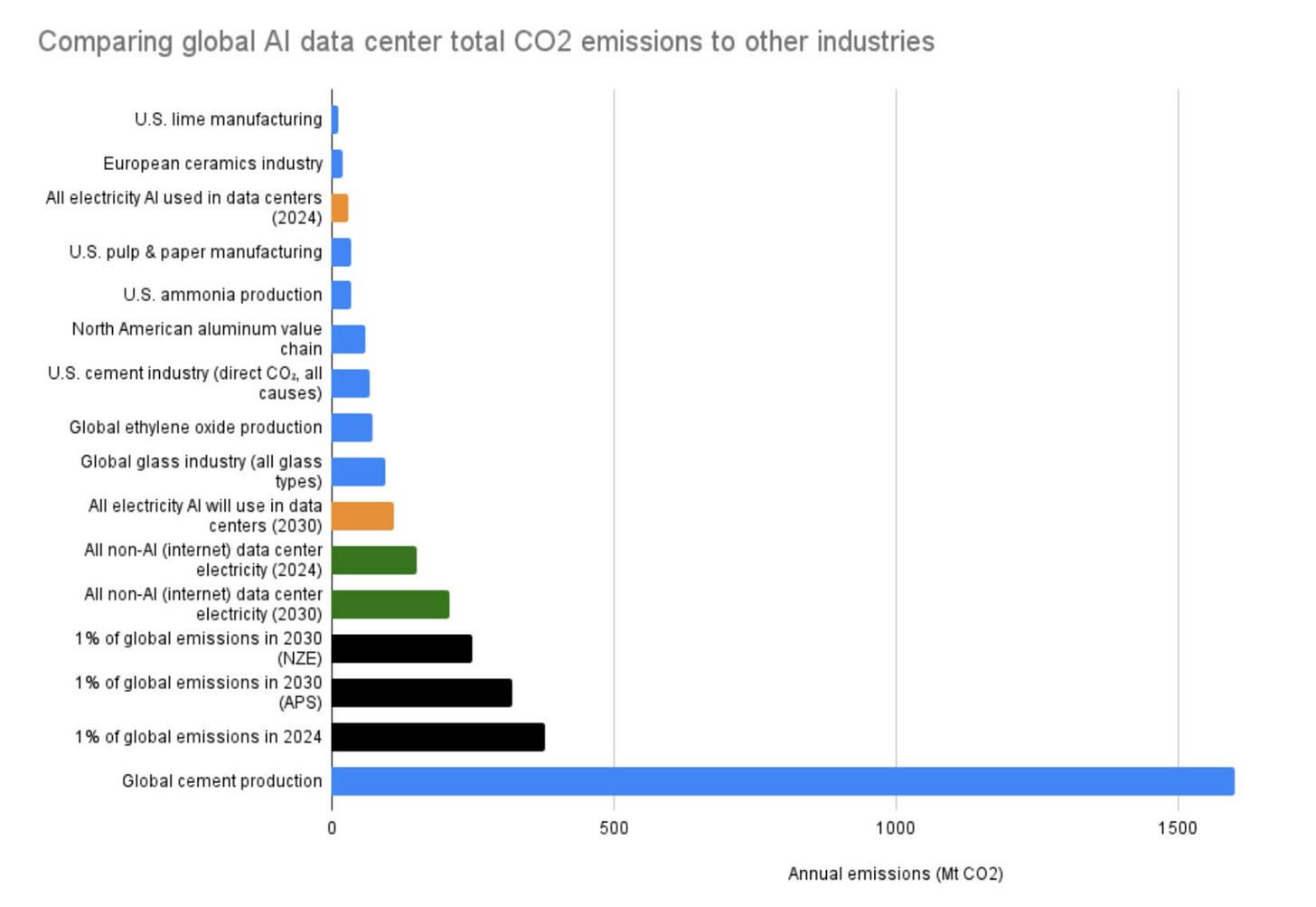

The IEA forecasts that data center emissions will peak in 2030. This is what their emissions look like now, and will look like in 2030, compared to other industries and emissions overall. I’ve split them up into the IEA’s implied forecasts for AI specifically and non-AI applications:

Again, not nothing, but the 2030 numbers are the very most emissions data centers are forecasted to ever cause in one year.

Unlike most other things on this list, data centers can help us in basically every other area of climate. Having very general tools to do immense numbers of calculations and optimization tasks is useful for tackling other problems. Of all the areas I’d want to cut for the climate, having giant warehouse-sized calculators for these tasks seems like one of the last places to cut. Even though data centers are newer, they’ll probably be much more useful for solving the climate crisis than most other industries.

But these other industries don’t have big evil buildings of their own. They have much more effectively hidden their emissions from everyday people, or normalized them so people treat them as permanent unchangeable background parts of the world. If we want to think seriously about climate, we need to be willing to slice through those illusions and think of the whole world as more malleable. When we do that, data centers stop standing out. They take their place among other very energy-optimized industries that serve a lot of people and emit relatively tiny amounts per user, and the main climate villains (things like cars, livestock, and bad energy management in buildings) become more apparent.

More than anything else, it’s the energy grid itself that needs to change, rather than the relatively small individual ways we use energy. 1.5% of electricity in the world is being used on computing in data centers. The problem isn’t that this number should move from 1.5 to 0% (computing is incredibly valuable!), it’s that 100% of electricity should be green in the first place.

None of this is to say that data center emissions don’t matter at all, only that they’re taking up a suspiciously large part of the climate conversation relative to how much they actually emit, or how beneficial it would be to stop building them.

If cars or livestock or energy waste had their own big evil buildings, it would become much more obvious how big of a climate disaster each is. It’s our job as people thinking about climate to make the invisible visible.

"...normalized them so people treat them as permanent unchangeable background parts of the world. If we want to think seriously about climate, we need to be willing to slice through those illusions and think of the whole world as more malleable"

I think this is the real point and data centers are the flavor of the month. For whatever reason people just seem bad at context and calibrating. Every endeavor we take on has pro and cons and those should be viewed against realistic alternatives and the cost of doing nothing.

IMO, it is about hating big companies. Make them the badguys. Us vs Evil Capitalism!

Etc.