If we let ourselves, we shall always be waiting for some distraction or other to end before we can really get down to our work. The only people who achieve much are those who want knowledge so badly that they seek it while the conditions are still unfavorable. Favorable conditions never come.

-C.S. Lewis

Learning a lot of actually useful information is drastically important. It’s maybe the most important thing you can do with your time to improve your life and become more able to act in the world. It’s easy to let a lot of time slip away without actually learning a lot, even if you’re at an elite school or in a cognitively demanding job. Actual consistent learning requires a lot of vigilance, self-reflection, mental fortitude, useful strategies and tools, and accountability systems.

In my experience, people everywhere are deeply excited about finding anyone who’s actually put a lot of time and thought into learning about something and thinking seriously about it, rather than just learning surface level knowledge and knowing the right “passwords” to say at the right time. I experience some people as having a uniquely warm glow of aliveness to them. A sense of presence. Just being in the room with them makes me feel like I have deep company. These people come from very different parts of my life and have very different backgrounds and beliefs. The thing they have in common is that they’ve put effort into actually learning a lot about the world, but are still radically open to new ideas and haven’t walled themselves off from unfamiliar situations and ways of thinking and living. I think putting a lot of careful effort into authentic learning can give you that same glow and can make your personal life (as well as your career) much better.

I’ve collected some useful ways of learning and thinking about learning. These mostly come from ridiculously knowledgeable friends I’ve tried to imitate, authors I like who have written about learning, and my own experiences with my own learning and as a teacher.

I’ve split the post up into Mindset and Tools. Your mindset about learning matters a lot, because what causes people to get stuck in their learning often has more to do with their internal sense of status rather than a lack of information or useful tools.

Contents

Mindset

Learning vs. pretending to learn

Memorizing passwords

Forgive me for what I’m about to type, but I enjoyed this Eliezer post on memorizing passwords vs. actually understanding something.

Children get a lot of early examples of smart people who actually just know passwords. A password is basically just a tool to say “Look! I’ve spent hours learning about a topic and have come away with this useful signal that I’ve learned it. It won’t actually help me operate in the world, but just saying it gives me a sense of status as a smart person. You’re obligated to give me status if I say it!” A lot of schooling involves learning passwords.

This can get grim if you meet someone who’s spent their whole life learning about a topic, but who has mostly been prioritizing passwords that they think will give them status instead of actually trying to understand the world. I have some memories of visiting someone’s home as a kid and seeing their walls lined with books about specific topics. This was exciting because they had clearly spent decades of their lives learning and I wanted to hear what they had to say. However, when I started to ask questions about what they had learned, they seemed much more interested in showing me that they could repeat the lines that signaled they were the type of person who had read a lot about the subject. They would always force the conversation back to opportunities to show what they knew, instead of bringing what they knew into contexts where it was useful.

Trying to hold onto the distinction between actually learning and just memorizing passwords is psychologically difficult, because we’re all driven by social status and want to be seen as smart and competent. Asking yourself “Have I actually learned something? Or have I learned a new party trick or way of showing that I’m an intellectual?” is difficult, but vital for actually understanding the world.

Pretending to learn feels good. Actual learning often feels bad.

A lot of people are just pretending to learn (memorizing passwords) when they think they’re learning.

This is a quote from the first volume of Knausgård’s autobiography where he gives my favorite description of pretending to learn and the good feelings that come with it. It’s long but worth reading:

Espen probably didn’t know this himself, since I always pretended to know most things, but he pulled me up into the world of advanced literature, where you wrote essays about a line of Dante, where nothing could be made complex enough, where art dealt with the supreme, not in a high-flown sense because it was the modernist canon with which we were engaged, but in the sense of the ungraspable, which was best illustrated by Blanchot’s description of Orpheus’s gaze, the night of the night, the negation of the negation, which of course was in some way above the trivial and in many ways wretched lives we lived, but what I learned was that also our ludicrously inconsequential lives, in which we could not attain anything of what we wanted, nothing, in which everything was beyond our abilities and power, had a part in this world, and thus also in the supreme, for books existed, you only had to read them, no one but myself could exclude me from them. You just had to reach up.

Modernist literature with all its vast apparatus was an instrument, a form of perception, and once absorbed, the insights it brought could be rejected without its essence being lost, even the form endured, and it could then be applied to your own life, your own fascinations, which could then suddenly appear in a completely new and significant light. Espen took that path, and I followed him, like a brainless puppy, it was true, but I did follow him. I leafed through Adorno, read some pages of Benjamin, sat bowed over Blanchot for a few days, had a look at Derrida and Foucault, had a go at Kristeva, Lacan, Deleuze, while poems by Ekelöf, Björling, Pound, Mallarmé, Rilke, Trakl, Ashbery, Mandelstam, Lunden, Thomsen, and Hauge floated around, on which I never spent more than a few minutes, I read them as prose, like a book by MacLean or Bagley, and learned nothing, understood nothing, but just having contact with them, having their books in the bookcase, led to a shifting of consciousness, just knowing they existed was an enrichment, and if they didn’t furnish me with insights I became all the richer for intuitions and feelings.

Now this wasn’t really anything to beat the drums with in an exam or during a discussion, but that wasn’t what I, the king of approximation, was after. I was after enrichment. And what enriched me while reading Adorno, for example, lay not in what I read but in the perception of myself while I was reading. I was someone who read Adorno!

A lot of people do the same thing as Knausgård. They read whole books just for the feeling of being the type of person who reads them, and retain no actual information about the world.

Avoiding playing pretend during your valuable learning time is important and psychologically difficult. A lot of people’s learning is limited by their insecurities and need for their social status to be reinforced. It often feels amazing to pretend to learn things, and unpleasant to actually learn. People are drawn to activities that make them feel high status, and repelled from activities that make them feel low status. Actually learning often involves wrestling with strange new ideas that make you feel stupid and that might not fit neatly into your pre-existing worldview. You might learn about whole systems of human endeavor that have nothing to do with what you’ve valued in your own life, or ways of thinking about science or philosophy or art or poetry that obviously confer a lot of status to people who spend decades thinking about them, but that you have just begun to think about. Openness to what you don’t understand is emotionally challenging, and gets harder as you age. Learning basic economics or calculus for the first time at age 15 feels exciting. Learning either for the first time at 30 makes you feel like you missed important opportunities and that you have limited time left. Most people most of the time avoid situations that are such direct reminders of their own limitations. I’ve come around to thinking that being good at powering through these hits to your ego is a core life skill, and just avoiding hits to your ego is maybe the main way you can get stuck and stagnant in life.

To avoid pretending to learn, you should focus on choosing material that will actually help you learn, setting clear specific goals for what you’re hoping to learn, build systems that test whether you’re actually learning, and try to become more psychologically resilient to feeling stupid and bad in a new subject.

This point was made well in a short simple book called Why Don’t Students Like School? which had a big influence on me as a teacher.

Psychological resilience to feeling stupid and accepting how little you know

A similar unpleasant part of learning is realizing that depth of your understanding of the world is often an illusion. You may imagine that you’ve thought about a topic for years, but when you examine what you actually know you realize that all you have is 5 or 6 simple slogans about the topic you repeat in your head a lot.

I had a reputation for knowing a lot about philosophy in college. I ran my college’s philosophy club for 3 years and did well in my philosophy courses. I put a lot of time and effort into learning about philosophy, and had a puffed up sense of status about it. Years later, I became friends with a former philosophy major who clearly knew a lot more about each area of philosophy than I did. I was excited to talk to him but was disturbed by how quickly what I thought was my deep knowledge of philosophy caved and crumbed, and turned out to be just a few slogans. I remember a conversation about philosophy of language being especially disturbing, where I realized most of my knowledge of it was basically just a few memorized thought experiments without an underlying grasp of how language worked. This was a huge status hit and felt pretty bad. I felt like I had spent a lot of time basically playing mental games with myself tricking myself into thinking I was knowledgeable about this. It feels very childish. The experience was pretty unpleasant, but necessary to help me learn more. The status hit was a necessary obstacle to overcome.

You need to build in lots of opportunities to bump into the limits of your own knowledge. Otherwise, it’s easy to pretend that you understand a subject for years without noticing how little you actually know. A good trick to discover the actual depth of your understanding of a topic is writing to learn (discussed more below). It can be disorienting to sit down to type out a simple essay about something you’ve thought about for years, and then finding you maybe have 4 or 5 sentences to type about it before hitting a wall. Another useful trick is just answering questions about the topic with other people (or LLMs).

Accepting that a lot of what you’ve learned might be a sunk cost

In college I spent a pretty ridiculous amount of time reading about Marxism. I was interested in leftist politics and could tell that a lot of leftist discussions came with the presumption that Marxism was correct. I figured that regardless of whether Marxism was correct, it would be worth understanding to swim in leftist ideological waters. I read most of Marx’s major works and learned the ins and outs of Hegel and Gramsci and Althusser and the rivalries between Rosa Luxemburg and Lenin and Mao and Zhou Enlai and Trotsky and Stalin. All of this turned out to be basically useless and a waste of time, for three reasons:

I became less interested in far-left politics and realized that the core ideas of Marxism are wrong for simple boring reasons.

The far left in America didn’t end up being nearly as important or influential as I expected it to be in 2011.

Most leftists themselves didn’t actually seem to care much about the details of Marxism and were kind of sloppy with how they applied the ideas, so knowing a lot about Marxism didn’t help much in conversations with them.

A similar problem happened with education and pedagogy. I spent a year learning about a lot of different pedagogical theories while I was training to be a teacher before realizing that almost none of them replicated and the whole field is completely awash in fake studies and vibes. Another year wasted!

I could have saved a lot of time in both cases just accepting that everything I had learned so far was a waste of time, but I powered through and kept learning about both for too long because I was irrationally hoping that they would turn out to be useful. Learning to accept and move away from sunk costs earlier would have been useful.

Some useful ideas to hold on to while you feel stupid in a new subject

These are some ways I motivate myself to power through the unpleasant feeling of learning new difficult stuff.

Feeling high status in other ways

It makes it easier for me to learn about macroeconomics knowing that I have a strong network of friends who will hang out with me even if I don’t know the deal with macroeconomics. This sounds silly, but we’re social animals and the background feeling of social stability I feel makes it much easier to take status hits in other areas.

Thinking in terms of compound interest about how much more knowledgeable you could be with effort

Day to day, I often feel pretty stupid in trying to learn new topics, but over time the compound interest of learning a lot begins to build up and I notice that I have a much deeper well of knowledge to draw from. I’ve met a lot of people in life who at first seem fundamentally much more capable than me, almost like they’re a different species. Over time and interacting with them I start to notice the rungs of the ladder they used to get to where they are, and it’s usually the result of daily diligent learning and the resulting compound interest of that. Interviews I saw as a teenager with thinkers who looked impossibly smart are funny to come back to years later with more context. A lot of them end up looking simple and even ridiculous. Compound interest reveals new vistas to you. The more you learn about a topic, the easier it is to take in new knowledge about the same topic, so an expert might be able to ingest new knowledge at something like 100x the rate of a novice. Reminding yourself that learning can turn you into a radically better version of yourself through the power of compounding returns can be incredibly motivating.

Little things add up

I listen to audiobooks on my walk to work and in the gym. My walk to work is 10 minutes there and 10 minutes back. 20 extra minutes per day of reading doesn’t seem like much, but over the course of a year that’s an additional 75 hours of reading. At the rate I listen to audiobooks that’s about 3,800 additional pages of reading. The gym is an hour, so over the course of a year that’s an additional 16,000 pages of reading per year. All because I’m making a daily decision to hit play on an audiobook instead of music. There are a lot of small pieces of low hanging fruit that yield ridiculously overpowered results like that you can find in your daily life.

Balancing the facts that a lot of people just pretend to know stuff and their knowledge about a lot is very surface level with the fact that people can and do possess deep important knowledge that it takes a lot of work to access

It is both the case that there is a lot of bullshit and a lot of deep knowledge to be had in the world. It can be demotivating to see how far you can get just bullshitting, but I’ve basically never regretted putting a lot of time into learning about subjects I was pretty sure were useful to understanding the world. For any one field, most people don’t know very much about it at all, but a few do, and the rewards for being in the select few who do are often very high.

Your time to learn is crushingly short, because life is crushingly short. Use it well.

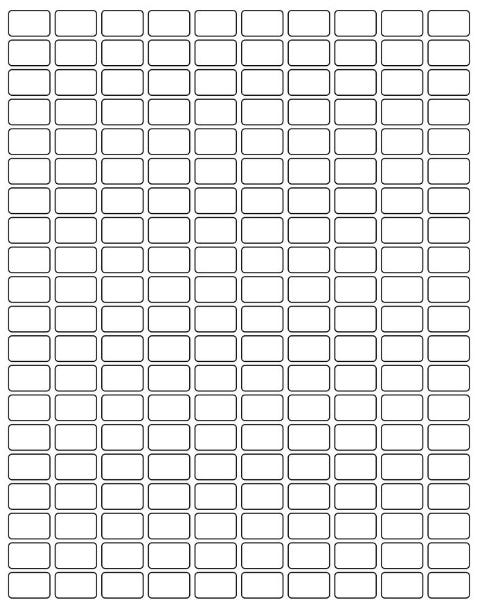

Picking up a book to read doesn’t feel like a huge decision, but unfortunately life is so short that every specific long book project you take on will be a significant chunk of your total lifetime reading. If you read 20 books per year, your entire 20’s will consist of just 200 books. Look at this image of 200 squares. Think of each one as a book you get to read in your youth. How many of these would you fill up with books that don’t matter very much to you?

There are 168 hours per week. Each hour is valuable. Choose how you use them well.

Abyss Staring as a Core Life Skill

I enjoyed this blog post on learning to face unpleasant facts as a pretty important tool for success. Building resilience to unpleasant facts might help you learn more!

Tools

Use spaced repetition

Spaced repetition is the most powerful single tool for learning you can use. There’s a lot of data backing this up. Andy Matuschak has a good summary of spaced repetition here and a good comparison between spaced repetition and just using books to learn here. I use Obsidian for notes and just use its spaced repetition plugin. I should be using it more!

Choose what to learn

Prioritizing what to learn has a ridiculous payoff. It can give you a massive leg up over people who are less disciplined about what they focus on.

A lot of the world exists in power law distribution, where effectiveness is tightly clustered at one end of an axis. Take global health interventions ranked by their cost effectiveness in DALYs per dollar spent:

Choosing what to learn has, I suspect, a similar power law distribution. It’s much much much more useful for acting in the world to have a basic grasp of mainstream economics than to learn the nitty gritty of Dune lore. Being very honest with yourself about what’s going to be worthwhile to learn about can be very difficult, but worth it for seeking out especially useful information.

A lot of things people choose to learn about are fake. I mentioned two examples I fell victim to above (Marxism and a lot of pedagogy theory). Being honest with yourself and adjusting what you learn to what you actually think is useful will go a long way.

Identify core important facts about the world to build a general worldview around

It’s helpful to have a cluster of ideas you mostly don’t have to think to question that can act as a kind of foundation you can lean up against when you’re engaging with new ideas. You should obviously still be open to questioning these, but having a short list of stuff you mostly don’t think to question can help you build a basic narrative to understand the world that you can attach new facts to. My list would include these:

Evolution is true.

Energy is conserved.

Magic isn’t real.

A lot of human civilization can be understood as a way of creating more and more incentives for more and more complex positive-sum interactions.

Start with a simple narrative you can attach facts to later

A few years ago I decided to try to learn a lot more about China. I started with a pretty simple book called Wealth and Power that gave simple biographical sketches of important people in modern Chinese history. Having major figures in Chinese history in my head as simple characters was actually pretty useful, even though it drastically simplified reality. The actual history is incredibly complicated, but having a basic story I could make more complicated over time made it much easier to learn than diving into more nuanced reading at the start. Don’t be afraid of starting off with an incredibly simplistic narrative of the world. You just need to add complexity to it later.

Commit to strong beliefs when you’re first learning about a new subject and then adjust them over time, instead of staying uncertain the whole time

A surprisingly powerful trick when you’re learning about a new field is to start off by committing to strong beliefs about core facts and adjusting that belief over time based on evidence, instead of going in with an open mind. This is counter-intuitive, but has worked for me in a lot of fields.

I used this trick to learn more about philosophy of mind. There’s a core debate in philosophy of mind about whether qualia exist. I could have read a lot of papers while maintaining total uncertainty about qualia (which is rational, since I don’t have nearly enough of a background to have a strong opinion) but if I did that a lot of the ideas wouldn’t stand out as much. With a strong belief about qualia, I’d bump into facts and say “Wow, this sticks out a lot as challenging my view, it seems pretty important!” Pre-committing to a strong belief and then adjusting it can be surprisingly powerful as a mental trick to retain more information.

Choose material that will actually help you learn

I feel great whenever I listen to a podcast about something I already understand or agree with. It’s nice to hear confident-sounding people say things that I can predict and understand but that I know a lot of people don’t know about. I could spend days doing this, but it’s a clear example of pretending to learn. It’s a game I’m playing with myself to feel smart. I know that if I swapped a podcast with a dry audiobook on a subject I don’t understand well I won’t be having as much fun, but I’m likely to learn a lot more. Making the decision every morning on my walk to work to listen to a drier but more informative audiobook feels meaningless in the moment, but it adds up to an additional 75 hours of reading time over a year. Making a list of types of material that help you actually learn vs. material that just makes you feel smart is useful as a first step to learning more. This will be different for each person. Experiment and try to figure out what works best for you and then prioritize that!

Build systems to test yourself

Spaced repetition, diligent note taking, and writing to learn are the three systems I use that help me test my learning. There are probably lots of other things you can be doing to test yourself. Try to find systems that work for you in examining your own learning.

Take lots of notes

Having a good note taking system is surprisingly powerful on its own for retaining information. I use Obsidian for notes and try to mimic Andy Matchusek’s system of taking evergreen notes. I think of Obsidian as building my own personal Wikipedia of information about the world relevant to me specifically.

Talk to knowledgeable friends

If you have a friend who’s knowledgeable about a topic you’re trying to learn about, just meeting with them and bouncing ideas back and forth can be ridiculously overpowered. 1-on-1 meetings for learning about a field are just incredibly useful. Among other things, an expert in a subject is much better at detecting small subtle mistakes you might be making and directing you toward the most important material and ways of thinking in the field. The social ritual of signifying what’s most important in a field can also be really useful to help you intuit what to prioritize.

Use LLMs

I try to spend at least half an hour a day writing back and forth with an LLM about something I’m trying to learn about. If you haven’t played with Claude or ChatGPT yet you’re missing out on one of the most useful new learning opportunities that exists right now. LLMs are like a much more responsive Wikipedia that can understand even vague questions or uncertainties you have about a topic.

Write to learn

If writing down your ideas always makes them more precise and more complete, then no one who hasn't written about a topic has fully formed ideas about it. And someone who never writes has no fully formed ideas about anything nontrivial.

It feels to them as if they do, especially if they're not in the habit of critically examining their own thinking. Ideas can feel complete. It's only when you try to put them into words that you discover they're not. So if you never subject your ideas to that test, you'll not only never have fully formed ideas, but also never realize it. - Paul Graham, in Putting Ideas into Words

That Paul Graham piece and this Holden Karnofsky piece are useful summaries of how and why to write to learn. In the same way that you need a pencil and paper to do math, you arguably also need writing to do complex thinking. I sometimes like to think about my writing as a part of my extended mind. A lot of my thinking has happened outside of my brain. I’ve found that I’m ridiculously more articulate in conversations about topics I’ve taken some time to write about. It feels like magic.

Wikipedia & similar

Wikipedia is underrated as a learning resource. The writing is direct and comprehensive. Setting a goal of reading x number of Wikipedia articles each day on a relevant topic and taking notes might give you more useful knowledge than most other ways of learning about it.

The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy is a similar resource. It’s ridiculously underrated for learning about philosophy. Reading articles there can give you a more comprehensive understanding of a philosophy topic than a majority of the individual philosophy books I’ve read.

Rituals that help you focus on learning

I have three tools for reading a lot that have helped me get a lot more learning time in.

A nice e-reader (I have a Kobo Libra Color) that doesn’t let you browse the internet. It’s very calming to just sit back without the ability to scroll and focus entirely on a book for long periods of time.

A text-to-speech app for listening to articles and books. I use this to get a lot of additional reading in during the day. text-to-speech apps have become much better in the last few years thanks to AI. Basically anything you want to read can now be uploaded and turned into a decent audiobook. I use Speechify.

Hanging out with friends who are also reading. I have a few friends I’ll meet to read with at a cafe or library. This hacks my social brain and helps me focus for much longer periods of time.

Finding rituals like this that guide you to learn more can make your learning feel more relaxing and less forced.

Recommended Resources

Andy Matuschak’s website has a lot of great resources on learning to learn

The Obsidian subreddit has useful tips on note taking

I’ve heard good things about this book but haven’t explored it as much

Great article. Two minor quibbles. I'm not sure learning through Audiobooks is actually effective. Retention seems to be much lower than actual reading. Secondly, I'm not sure that economics is any more "real" than Marxism. We just live in a society that has bought into the collective delusion of classical economics, which makes it more useful than Marxism, at least in the West, but doesn't make it any more true. There are just too many contradictions between economics and ecology for it to really hold up.

Wonderful read! I would just like to add few things. One should read to just read too. Read because you enjoy reading not always because you have some goal or some intention to get out of that read/book/article. Let yourself wander in new territories just because you like to read.

And fiction is as important as non fiction maybe sometimes more too, as C.S Lewis also said :

"Some day you will be old enough to start reading fairy tales again"