Ideas from philosophy I use to think about AI

Physicalism, functionalism, and lots of Quine

Contents

Goals for this series

Share useful ideas and heuristics

In this post series I’ll write about ideas and heuristics I use to think about AI. They range from “seems right” to “core part of my belief system.” Each of them seems sufficiently non-obvious in broader discussions about AI that I want to articulate them in one place. I’ve tried to make these posts fun and include links to some of my favorite essays, books, and videos. AI touches on so many other interesting subjects that it becomes a fun lens through which to think about the world in general.

AI looks like it’s going to be a big deal. It’s suddenly coming up in conversations a lot more among friends and in the news. Even friends who previously showed no interest in it now bring it up early in conversations. I’ve been lucky to have conversations with brilliant people with wildly different beliefs about AI and the future, and have a decade and a half under my belt of learning about topics that have turned out to matter a lot for AI, especially philosophy of mind, ethics, physics, computer science, economics, and climate change. I have a degree in philosophy and physics, but besides that all my takes here are amateur level. Even amateur-level takes can be useful in learning about AI, because right now the topic rewards knowing a little about a lot of different stuff.

Normalize my beliefs in conversations about AI

A lot of the rules I consider pretty fundamental to how I think about the world are sometimes dismissed out of hand in popular conversations about AI. I don’t expect everyone to agree with me, but most of my takes are within the range of reasonable opinions held by experts, so I do expect people to take them seriously as one of many debatable positions rather than dismissing them. I’d go so far as to say that refusing to engage with any of these rules is a sign of deep incuriosity that is bad for thinking and talking about the world. I’m putting them forward in this post and asking you to consider and respect them as one of many reasonable options, not to assume they all must be true.

One obvious example: many people confidently say that AI can never do what the human brain can do, because AI is a machine. I’m a physicalist and think that every aspect of the human brain that has any causal power on anything else must be a physical process. If we define a machine as any physical system that processes information, follows deterministic or probabilistic rules, and produces outputs based on inputs, then under physicalism, the human brain is just a very complex machine. Thus, a machine that can do everything the human brain can do is possible in principle, because the human brain itself is a machine. 52% of professional philosophers accept or lean towards physicalism, and that number rises to 60% when you specifically poll philosophers of mind, so this isn’t a fringe belief among experts (it’s the majority view!), but in popular conversations about AI the idea that the human brain is a machine is sometimes treated as a crazed tech-bro belief that misses vital parts of the human experience. This seems like an immature and incurious dismissal of serious philosophy. There are plenty of great arguments against physicalism, but I don’t know of any philosopher who goes around saying physicalism is only for crazy stupid people. I do bump into people saying that regularly in conversations about AI. I don’t expect everyone to agree with physicalism, but I do expect them to treat physicalism as one serious possibility that enough experts believe in to give it serious consideration. This applies to the rest of these ideas as well.

Sharing useful fields to read more about

I wish I could go back in time to tell past me to read a lot about growth models or Quine or climate economics or biology. Even if your thinking about AI doesn’t change after reading this, I hope I can give you some fun rabbit holes to go down. In some ways I’m writing this as the guide I wish my 18-year-old self had—an introduction to what I consider the most compelling ways of thinking about the world.

Ideas from philosophy I use to think about AI

There is nothing fundamentally magical happening in the human brain

Physicalism is the idea that everything that exists (or at least everything that has causal power over physical entities) is physical (either described by or used by the laws of physics). I’m a physicalist. My argument for physicalism is simple:

Our current understanding of physics is almost certainly correct or at least very close to it. Future refinements will likely involve minor adjustments to physical properties, not the discovery of an entirely new non-physical realm interacting with the physical world.

The laws of physics state that only physical entities—those governed by or described within these laws—can causally affect other physical entities. If non-physical entities could causally influence physical entities, this would violate the known laws of physics.

Therefore, non-physical entities cannot have causal power over physical entities. For practical purposes it is as if they don’t exist.

52% of professional philosophers accept or lean towards physicalism, and that number rises to 60% when we specifically poll philosophers of mind. You can read some of the best arguments for and against physicalism in this article.

As a good physicalist, I assume that everything happening in the human brain ultimately has to be reducible to physics. This means that a machine that can do everything the brain can do is possible in principle, because the brain is a machine. This doesn’t mean that the brain is a computer. It might be that we’re thousands of years away from completely mimicking the human brain in a machine and would need an entirely different paradigm of science we can’t imagine yet to do it, or it will happen tomorrow under the current AI paradigm. Either way, it’s at least possible in principle.

Physicalism is surprisingly unpopular in mainstream conversations about AI. The reason might be that most Americans are religious and believe in souls, but the assumption that the human mind is magic often shows up even among nonreligious people. The mind is obviously special. Nothing in the universe is more complex, interesting, or poorly understood relative to its importance to us. However, many conversations go beyond this to say that there is something so fundamentally transcendent about the human mind that it can never be fully replicated by a machine, and to believe otherwise is a ridiculous oversimplification of human experience. Some authors use more ominous language to describe people who believe that AI might someday be able to do everything humans can do. They accuse them of wanting to steamroll human experience or contort people into unnatural/hyper-capitalist/emotionless robots to meet the demands of the market. If you’re familiar with the current debates in philosophy of mind, this quick dismissal of the idea that the mind is fundamentally physical in nature seems very strange. It’s fine to disagree with physicalism, but to not even entertain the idea or anyone who believes it shows a lack of curiosity about the current state of philosophy of mind.

If physicalism is true, then functionalism is likely true as well—implying that mental states can arise in machines very different from the human brain.

Functionalism is a theory about the nature of mental states in philosophy of mind. Before we talk about it, we need to explore the question it’s trying to answer.

What is a mental state?

One of the core debates in philosophy of mind is about what makes something a mental state. For example, what causes the actual mental state of pain to occur, rather than just the outer appearance of pain? If a doll is programmed to say “ouch” when you press a button, this has the outer appearance of pain, but we know there’s no actual inner mental state that’s anything like the human experience of pain. What is it about a human that causes them to experience the mental state of pain that’s different from the doll? Also, what do we mean when we call pain a mental state?

This debate matters for AI because our answer will tell us whether specific mental states can occur in AI systems, aliens, animals, or other non-human entities.

One possible answer is that specific mental states only occur in ethereal souls completely disconnected from physical reality. The doll doesn’t have a soul, so it can’t feel pain, whereas humans do have souls that can be in specific states, like pain. This view would say that because AI does not have an ethereal soul disconnected from physical reality, it can never be in the mental state of pain.

Another answer (the mind/brain identity theory) says that mental states are identical to very specific physical processes in brains. For example, C-fibers are a type of nerve fiber responsible for transmitting pain signals in humans. Under the mind/brain identity theory, saying “I’m in pain” is identical to saying “My nervous system’s C-fibers are firing.” Pain is just the physical process of C-fiber firing. The doll does not have C-fibers, but humans do, so the doll cannot experience the mental state of pain because it does not have the thing that pain is: firing C-fibers. An AI could never feel pain unless we somehow gave it real C-fibers.

Both of these above theories are popular in everyday conversations about how the mind works, but deeply unpopular among philosophers of mind.

The soul theory is unpopular because many philosophers of mind are physicalists, and even if you’re not a physicalist there is a noticeable deep association between brain states and mental states. It would be surprising if they were entirely separate from each other.

The mind/brain identity theory is unpopular for more complicated reasons:

Multiple realizability

Hilary Putnam argued that if pain were strictly identical to C-fiber firing, then only beings with C-fibers could feel pain. But many creatures—like octopuses, which lack C-fibers—clearly feel pain. This suggests that pain must be defined functionally, not as a specific brain process, because it can be realized in different biological or even artificial systems. Even within humans, pain does not correspond neatly to just C-fiber firing—there are other pathways and neurological structures involved. This weakens the idea that there is a single physical correlate for every mental state.

Qualia

Some philosophers argue that pain is not just neural activity because it has a subjective quality, or qualia: the “what it feels like” aspect of experience. Thomas Nagel’s What Is It Like to Be a Bat and Frank Jackson’s knowledge argument both push against the idea that mental states are reducible to specific physical events.

The other competing accounts of mental states include dualism (mental states are not purely physical) and functionalism. Because we’re assuming physicalism, we can ignore dualism for now (you can read a lot more about it here).

What is functionalism?

From the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy:

Functionalism in the philosophy of mind is the doctrine that what makes something a mental state of a particular type does not depend on its internal constitution, but rather on the way it functions, or the role it plays, in the system of which it is a part.

Functionalism’s main claim is that mental states are defined by what they do, not what they’re made of.

Among professional philosophers, functionalism is the most popular account of mental states.

A mathematical function takes an input and produces an output. Functionalists imagine mental states as being in some sense very complex mental functions that take specific inputs and give outputs. The thing that makes something physical pain is that it has the same effects on my broader mental system given the same inputs, not that its cause is a very specific physical part of my brain made of a specific substance.

An argument for functionalism, presuming physicalism

Suppose that we were able to replace exactly one neuron in my brain with a silicon chip that could send and receive exactly the same electrical impulses at exactly the same times as the neuron. Maybe there’s something about the substrate of silicon that prevents it from replacing all the functionality of a neuron, but let’s presume for now that it can send and receive all information the neuron receives. What would happen?

Importantly, if physicalism is true, nothing about my behavior would change. There wouldn’t be some immaterial soul or something similar swooping in to say “Hey, Andy’s brain has something strange in it. Something’s off!” The same electrical impulses would happen in my brain either way and cause me to behave in the same way. The same inputs would lead to the same outputs. If I looked at a tree and said, “I see a tree” before replacing a neuron with a chip, I would say the same afterward.

So if physicalism is true, my behavior would stay the same after my neuron is replaced with a chip. What would happen to my conscious experience of the world? Let’s imagine I’m staring at a tree (I’m using an example of my conscious experience of my field of vision because it’s easier to make an image). It seems like there are maybe 4 options, shown below:

Option 1: No change - My conscious experience of the world doesn’t change.

Option 2: A little missing - Maybe some small specific part of my field of vision or something similar goes blank.

Option 3: Less consciousness - There’s less conscious experience in general. Maybe my experiences are more blurry or dim, like I’m in a dark room.

Option 4: No consciousness - I no longer have conscious experiences.

We’ve established that my behavior wouldn’t change. Physicalism implies that the same inputs would lead to exactly the same outputs. This would make option 2, 3, and 4 very strange, because I wouldn’t react to my conscious experience changing, because my outward behavior would be exactly identical to the before case. If I looked out at a tree, and my conscious experience included a small piece of the picture missing, I would notice that and comment on it: “What’s going on? There’s a black dot in my field of vision.” If there were less conscious experience in general, I’d probably say “My vision is suddenly very blurry.” If there were no conscious experience, I’d say “Aaaah! I can’t see!” Because my behavior doesn’t change, I don’t say any of these things, I say “Look! A tree!” This would be very strange behavior if 2, 3, or 4 were true.

I trust my current self’s reports about his conscious experiences. My speech about my conscious experience matches the experiences I’m having. I should probably trust silicon neuron brain Andy’s reports as well.

Maybe it’s possible that my conscious experience would be disconnected somehow from my physical behavior, where I’d be helplessly losing consciousness as my physical body behaved normally as if it were a robot. Unconscious silicon brain Andy would take over as normal brain Andy helplessly lost consciousness and died. This would be very strange, because most of my day to day behavior is responding to my conscious experience. If you somehow removed my conscious experience’s ability to affect my physical behavior, I’d behave in very physically different ways, because I’d be missing a lot of important information. I wouldn’t react to heat or cold or anything in my field of vision. I might behave as if I were dead. It seems like it’s very likely that my conscious experience wouldn’t be affected by replacing 1 neuron with a silicon chip.

We could then go ahead and replace a second neuron with a silicon chip. For the same reason, my conscious experience wouldn’t change. We could build special chemical receptors and signals to replace other parts of my brain. As long as they had the same inputs and outputs on my behavior, I wouldn’t expect my conscious experience to change. At the end, I’d have the same mental states as before, but my brain would now be made mostly of silicon and other materials. This thought experiment is evidence that functionalism is correct: what makes something a mental state depends on its inputs and outputs, not on the specific physical material the system creating that mental state is made of.

So we’ve established that if physicalism is true, it seems likely whether my mind is in a certain conscious state is that the same inputs lead to the same outputs, not the internal constitution of what’s creating those inputs and outputs (a neuron vs. a silicon chip). Physicalism seems to imply functionalism.

Functionalism implies that mental states can exist in material and systems very different to the human brain

Human-like mental states might only arise in brain-like material, as it uniquely processes information in specific ways to generate the required inputs and outputs. A brain composed entirely of hydrogen atoms is implausible, as hydrogen alone cannot facilitate complex information processing. However, if a system is able to reproduce all the same inputs and outputs as mental states as they occur in human minds, and is just made of different physical material, we should probably assume that it also has the same mental states as the human brain. I don’t think current AI as it exists is conscious, but it is possible in principle for a machine made of silicon to be conscious like humans if it can reproduce the same inputs and outputs of our relevant mental states. It might be that at a certain level of complexity AI could also have mental states vastly alien to what humans can experience, but that we would still consider conscious experience.

When I started studying philosophy the idea that only carbon-based life could have conscious experience seemed kind of obvious to me, but looking back it seems incredibly goofy. "For a being to have first-person experience, the atoms that make it up need to have exactly 6 protons."

Introspection is a bad way to understand our minds

A lot of the assumption that the human mind is special and not replicable by a machine comes from our strong sense that our minds contain depths of magic and mystery that we can tap into through introspection. While I think introspection has value, we shouldn’t overestimate what it can actually tell us. I think any claim based on first-person introspection about what AI will be able to do in the future is suspicious.

When we look out at the world, we impose pre-existing mental categories on our constant rush of experiences to try to make sense. I have pre-existing mental categories for “tree” and “my friend Paul” and “supply and demand.” Losing those would make reality hard to navigate. These mental categories don’t actually match anything fundamental about the world. As a good physicalist, I know that behind the veneer of my interpretations, reality is only the universal wave function. My mind is basically running a simulation of a much weirder and more complex reality, and giving me a lot of useful fictions and simplifications to get by. Most people believe this is true about our understanding of the external world, but they have very different beliefs about how we understand our internal world.

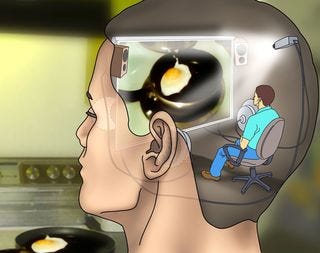

There’s a popular image of our inner mental self as a little version of us who lives in our heads observing our conscious experience directly. The windows to the outside might be blurry and full of distortions and useful fictions, but there’s nothing we have more direct familiar contact with than the inside of our own minds. Daniel Dennett calls this the “Cartesian Theater Theory of Mind” after Descartes, whose model of the mind centered the self as a background observer without qualities experiencing all our thoughts, feelings, and sense data. The Cartesian Theater is like a little person in our heads who can see the inner contents of our minds clearly, but who is watching the outside world like it’s a movie (with all the simplifications and distortions that a movie can have).

This doesn’t make sense from a physicalist perspective. There’s no little movie theater in our heads or inner room where pure ideas float before a Cartesian observer. If you’re a physicalist, you assume that the mind isn’t made of pictures floating in an ethereal realm of pure consciousness, it’s made of the flow of information through incredibly complex inputs and outputs. We use the same cognitive architecture to think about the inside of our minds as we do to think about the external world. In thinking about both, our brains come up with useful stories and generalizations to make sense of a much stranger and more complex underlying reality. We should have the same level of confidence in the stories we tell about our own inner experiences as we do about the stories we tell about the outside world. They’re distorted simplifications that help us get by, not fundamental reality presented perfectly clearly to us.

In some ways we’re probably much more deluded about the inside of our minds than the outside world, because our minds come prepackaged with an illusory sense of deep familiarity to us. We’ve evolved to actively deceive ourselves about our own motives and come up with post-hoc justifications for what we do. There are very good arguments for the idea that our sense of the present, our sense of ourselves as unified entities, and even our first-person conscious experience are complex illusions. None of this feels correct to me internally, but the arguments for each are so strong that it’s hard to deny them. These are each an area where I’m willing to override my first-person direct experience and assume the third-person arguments are correct.

It makes sense that we feel a deep personal sense of infinite importance and mental power, and in some ways that’s correct. The human mind is the only entity we know that can discover fundamental particles. But we shouldn’t assume that we can use introspection to detect a deep underlying magic to the human mind inaccessible to AI.

Two especially good texts on trusting our first-person intuitions about our own minds less are the opening of the essay Some Consequences of Four Incapacities by CS Pierce (up to the four denials) and the book Consciousness Explained by Daniel Dennett.

To predict the next word, it’s helpful to actually understand the world

LLMs are trained to predict the next word (or more precisely, the next token, which may not be a full word) in a string of text. The feedback they receive during training compares their guesses at the next token to actual next tokens.

A common criticism of LLMs is that they’re “just glorified auto-complete” because they are trained to predict the next word. I think a lot of people who say this don’t understand that next-token-prediction is just the part of the model that receives feedback about whether it’s getting the word right. It takes this feedback and sends it back through over 1 trillion parameters to adjust its intuitions, eventually detecting extremely subtle patterns that mimic what looks a lot like a model of the world. This and this video are great explanations of how this feedback happens and how an LLM might come to build a model of the world using that feedback.

Next-token prediction is similar to evolutionary natural selection. Both appear to be extremely simple algorithms and provide simple outputs to the system. Next-token prediction says “This word is more likely to be correct, that one is less likely to be correct” and tells the trillions of parameters of the AI to adjust accordingly. Natural selection says “This gene survived and reproduced, that one didn’t” and tells the animal’s DNA to adjust accordingly. However, these simple inputs are both acted on by an unbelievably complex reality. For words, all language and written knowledge of the world. For genes, all the complexities of nature, specific environments, and group competition. We can think of both simple algorithms as doors that allow the complexity of the world to enter and be used by the internal system of the AI/animal in a simple language its system can understand and respond to. Just as evolution has been able to build us unbelievably sophisticated bodies that can react to the world using the simple algorithm of natural selection, AI can be trained to build extremely complex internal systems to understand the world using the simple algorithm of next-token prediction.

To build your intuition about how AI is trained to predict the next token and how that can build an inner world of associations and understanding, I’d strongly recommend the full 3Blue1Brown video series on neural networks.

Ilya Sutskever gave a really brilliant example of why an AI given the simple reward function of predicting the next word will be incentivized to develop a world model and methods of reasoning:

So, I’d like to take a small detour and to give an analogy that will hopefully clarify why more accurate prediction of the next word leads to more understanding, real understanding. Let’s consider an example. Say you read a detective novel. It’s like complicated plot, a storyline, different characters, lots of events, mysteries like clues, it’s unclear. Then, let’s say that at the last page of the book, the detective has gathered all the clues, gathered all the people and saying, “okay, I’m going to reveal the identity of whoever committed the crime and that person’s name is”. Predict that word. Predict that word, exactly. My goodness. Right? Yeah, right. Now, there are many different words. But predicting those words better and better and better, the understanding of the text keeps on increasing. GPT-4 predicts the next word better.

Predicting the detective’s next word here clearly requires some kind of ability to model what is happening in the rest of the book. That model could be very different from how human minds work, but some kind of model would be necessary. If AI is able to correctly predict meaningful tokens for any and every question we ask it, the question starts to become why it matters whether it “understands” what it’s dealing with, and what we even mean when we say it understands in the first place.

Some people think that AI only memorizes canned responses to possible questions. This is not true. We can test this by asking AI some radically new question that it could not possibly have been trained to recognize, and see what happens. If you don’t think that AI “truly understands” the language it’s working with, it should be easy to come up with questions like this that clearly demonstrate that it’s just parroting words. Here’s a prompt I used to see if it can pick up on a lot of context

Prompt: Can you write me a broadway musical (with clearly labeled verses, choruses, bridges, etc.) number about Donald Rumsfeld preparing to invade Iraq while keeping it hidden that he's secretly Scooby-Doo? Please don't use any overly general language and add a lot of extremely specific references to both his life at the time, America and Iraq, and Scooby-Doo. Make the rhyme schemes complex.

If AI can give a good answer to literally any question humans throw at it, it starts to seem pointless to debate whether it “really, truly understands” the words we’re asking it to generate. Even if it doesn’t, it’s perfectly mimicking a system that does, so we’re getting the same value of it anyway. The next section cover whether humans even understand words at some deeper level beyond associations with other words and ideas. We might not!

Words don’t have clear meanings we deeply understand

A common critique of large language models is that they do not actually “understand” the language they’re working with in a deep sense. LLMs construct an incredibly complex vector space that encodes statistical relationships between words and ideas, allowing them to generate coherent text by predicting contextually appropriate continuations, but this is different from “truly understanding” language. If you’re not clear on what it means to encode statistical relationships in a complex vector space, I’d strongly recommend watching this and then this video.

I’m much more willing to assume that large language models actually “understand” language in the same way we do, because I suspect human language use is actually also just extremely complex pattern-matching and associations. One specific 20th century philosopher agrees.

Quine

Quine has maybe the widest gap I know between how important he was in his field relative to how well known he is to the general public. He was one of if not the most important of the 20th century analytic philosophers. I think that if you care about epistemology, language, or the mind, you should spend at least a few hours making sure you have a clear understanding of Quine’s project. Word and Object is one of only a few books I consider kind of holy. Sitting down to read it with an LLM to help you can be magic. Quine is so relevant to the current conversation about whether LLMs understand words that I’m going to use this section to run through his arguments in detail.

Two Dogmas of Empiricism

Until the mid 20th century, philosophers believed in a fundamental difference between analytic truths, certain knowable through pure reason and definition (“If someone is a bachelor, they are unmarried”), and synthetic truths, uncertain beliefs discoverable only through empirical investigation (“Tom is a bachelor”). This distinction paints a picture of language learning where we first learn fixed deep meanings of words, and then apply our understanding of language to our sense data to understand and try to predict reality. Before you label the person you’re experiencing a bachelor, you need to have a deep clear understanding of what the word bachelor means. Under this view, large language models skip the important step of grasping the deeper meaning of words before using them and comparing them to reality, so they do not truly understand the words they work with. One of Quine’s central projects was disproving this picture of language as divided between analytic truths of pure definition and synthetic truths about the real world. Quine’s image of language is more of a “web of belief” with stronger and weaker associations between different ideas, words, and experiences, and no firm ground on which to base absolute certain beliefs.

In "Two Dogmas of Empiricism" (one of the most important philosophy papers of the 20th century, you should take the time to read it if you haven’t! Here’s a good podcast episode about it) Quine shows that what we typically call "analytic truths" (truths that seem to come purely from the meanings of words) are actually grounded in the same kind of empirical observation as any other truth about the world.

When we try to justify why "bachelor" and "unmarried man" mean the same thing, we ultimately have to point to how people use these words. We observe that people use them interchangeably in similar situations. This is an empirical observation about behavior, not a logical discovery about the inherent nature of the words themselves. This can seem so obvious as to not be worth pointing out, but it highlights a way our sense of deep understanding the fundamental identity of “bachelor” and “unmarried man” is actually just a strong association between words, concepts, and experiences learned empirically through our sense data.

We can't justify analytic truths by appealing to synonyms, because our knowledge of synonyms comes from observing how words are used in the world. And we can't justify synonyms by appealing to definitions, because definitions are just more words whose meanings we learn through use.

One way of reframing what Quine is trying to say: philosophers have liked to imagine that there are specific types of beliefs we can be completely certain of (assign 100% probability to) because we learn them through pure logic rather than through experience. So it might be tempting to say that given that Tom is a bachelor, it is 100% likely that Tom is an unmarried male. This is an analytic truth, we can be 100% certain about it. The odds of Tom being a bachelor in the first place can never be 100% certain (he could be lying, we could be dreaming, etc.). This is a synthetic truth. We access it through unreliable sense data. Quine wants to show that our understanding of “bachelor” = “unmarried male” is learned via experience of the specific practices of people rather than a raw pure truth directly accessible in an ethereal realm, so we cannot assign 100% certainty to it. Saying “bachelor” = “unmarried male” is another way of saying “I have noticed that in this time and place, the situations people understand warrant saying “bachelor” always also warrant saying “unmarried male.” This is one observation in a web of belief of different observations and connected implications with different probabilities of being true that never hit 100%. Just like our other beliefs about the world, “bachelor” = “unmarried male” could theoretically be revised if patterns of word usage changed dramatically enough or if we are mistaken about reality in some other way.

For example, there are some males who are not legally married but who live with a lifelong committed monogamous partner (probably many more than when Quine was writing in the 50’s). Would you say one of these men is a “bachelor?” If not, “bachelor” no longer means “unmarried male” and that 100% reliable analytic truth turns out to be just another fallible belief constructed using sense data about the world: a synthetic truth. There is no strong difference between analytic and synthetic statements.

There are two related important points to draw from this:

The meanings of words do not exist in an ethereal realm of pure logic separate from our empirical observations and associations about the world. The analytic/synthetic distinction does not exist.

The meanings of words depend on how they are used, and are extremely ambiguous and can be updated by changes in behavior rather than changes in the deep understanding of meaning users of language have. The word “bachelor” has changed its meaning since the 1950s. This change did not come about by sending every English speaker a memo about the updated meaning of the word so they could think about and update their deep understanding of that meaning. It came about by the complex play of using the word at slightly different times in our social interactions with each other. The word’s strong associations with some experiences weakened, and other associations grew stronger. Like an LLM updating its weights to adjust when a word is likely to be correct based on subtle inputs rather than top-down rules, we adjusted our senses of when a word is appropriate to say and use based on subtle inputs from our social environments rather than a top down announcement from our fellow speakers. Quine will go further later and claim that words do not carry deep clear meanings that speakers need to grasp to use them correctly; their meanings are based on stronger and weaker associations between other words, experiences, and concepts.

A fun example of a word we use without deeply understanding its meaning is “game.” It is likely that you have never used the word “game” incorrectly and you’re good at identifying what is and is not a game. Do you have a deep understanding of the meaning of the word “game?” If you sit down and try to define what a game is, it turns out to be surprisingly hard.

Is a game something you play for fun? If so, professional football players never play games. They’re doing they jobs and aren’t on the field for fun. This definition is incomplete.

Is a game something you play with other people? Solitaire and a lot of video games wouldn’t count as games.

Maybe the unifying thing that a game is is that it’s something you “play,” but what does “play” mean? It seems like the one thing we know about it is that it’s often correct to say you’re “playing” when you’re participating in some kind of game. This seems more like a strong association between related words (something an LLM is good at) and not so much like we have some deep transcendent understanding of exactly what “play” and “game” refer to and how they fit together.

Quine would say that it makes sense that you can use “game” extremely competently without having a deep coherent idea of what it’s logically supposed to mean. When to use “game” is a complex subtle pattern you’ve empirically picked up through trial and error in the real world, not an absolute meaning you were given to use and apply. You see how other people use it, and you imitate them. Our acquisition of language seems to work more like this than the analytic/synthetic distinction suggested, and this implies that words might not have deeper meanings to understand beyond the complex webs of associations and social practices of which they are a part.

Radical indeterminacy of translation

In Word and Object, Quine developed his most famous thought experiment to show that words do not have fixed clear final meanings, but instead exist in a web of associations and practices. Meaning is not a simple matter of attaching words to things in the world but instead depends on broader interpretive frameworks.

Imagine a linguist trying to learn the language of a newly encountered community. A native speaker points at a rabbit and says “gavagai.” The linguist might reasonably assume this word means “rabbit.” But does it?

Quine points out that there is no definitive fact of the matter about what “gavagai” refers to. It could mean:

“Rabbit” (the whole animal, as we might assume)

“Undetached rabbit parts” (all the parts that currently make up the rabbit)

“Rabbit-stage” (a temporary phase in a rabbit’s existence, like “childhood” for a person)

“The spirit of a rabbit” (if the native culture has such a concept)

“Running creature” (if the speaker only uses the word for live, moving rabbits)

No amount of observation or experience can settle this question with certainty. The linguist can watch many more instances of people saying “gavagai” when rabbits are present, but this won’t eliminate the alternative interpretations. Even pointing at a rabbit repeatedly and saying “gavagai” won’t help—because what we see depends on the conceptual categories we already use.

At first, this argument seems like an issue of translation between different languages. But Quine goes much further: he claims that the same kind of indeterminacy exists within our own language. Even in English, when I say the word “rabbit,” what exactly am I referring to? Is it:

A specific animal in front of me?

The general category of rabbits?

The temporal stages of a rabbit (baby, adult, etc.)?

The matter that makes up the rabbit at this moment?

Most of the time, we don’t notice these ambiguities because we operate within a shared linguistic framework. But Quine’s point is that reference is never determined by the word alone—it always depends on a complex web of background assumptions, learned conventions, and shared interpretive strategies.

Quine is trying to challenge two common philosophical positions:

Meaning Empiricism: The idea that we learn word meanings purely by observing the world. (the thought experiment shows that observation alone is never enough to determine meaning.)

Meaning Realism: The idea that words have fixed, objective meanings independent of how we use them. (Quine shows that meanings shift depending on our theoretical perspective.)

Speakers of the same language can leave massive ambiguities about what objects they are attempting to refer to with their language unresolved, both with each other and even in their own thinking. This is a sign that words do not carry fixed deep meanings. There is no ultimate, fact-based answer to the question, “What does this word really mean?” Different frameworks can assign different meanings to the same linguistic behavior, and no external reality can dictate a single correct interpretation.

This conclusion applies not just to exotic languages or difficult cases but to ordinary language use in everyday life. When you speak, your words do not have fixed, intrinsic meanings—they are shaped by the assumptions, conventions, and interpretive frameworks of your community. Words do not point to fixed meanings in the world; instead, meaning emerges only within a broader system of use and interpretation.

Naturalism, physicalism, and the Cartesian theater

One thing that attracts me to Quine’s way of thinking is that it fits well with physicalism. Humans are not angelic beings with access to a transcendent realm of the pure logical meaning of words. We evolved via natural processes and are physical machines, and we should expect that our processes for understanding the world are evolved tools rather than direct access to realms of pure thought. Quine himself referred to his project as “naturalized epistemology” where he aimed to bring philosophy in line with and submit it to scrutiny by the natural sciences. We should assume that when we think, we are doing complex pattern-matching in similar ways to other animals. This deflationary view of meaning and language’s relationship to the world makes me suspect that LLMs as they exist are much farther along in mimicking the human brain than some might expect, because merely building lots of intuitions about how words associate with each other might be most of what we humans do to understand language.

Listening to people say that LLMs don’t “understand” the language they’re working with sometimes makes me suspect that they believe in the Cartesian Theater. The only way for an entity to understand something is if there’s a little guy sitting in its brain capable of understanding, like a soul. Because LLMs are just weights and nodes, that little guy can’t be in there. There are better criticisms of the idea that LLMs can truly understand the world, but if you find yourself in a conversation about whether LLMs “truly” understand language, it might be helpful to check to see if the person you’re talking to believes the human mind is transcendent and magical and understands all the words it uses in a deep powerful way because there’s a Cartesian theater in our heads. You can then introduce them to the good word of Quine.

There are probably ways of thinking and experiencing the world so alien to our brains that humans can never access them, but AI could

Ants have some forms of intelligence, but they can’t think about integrals or experience music or analyze poetry in the way we can. It seems unlikely that human cognition represents the final frontier of conscious experience. Just as listening to music is something humans can do that ants cannot, it is likely that there are similar step-changes that AI could experience in the future, because its cognitive architecture is so much less limited than humans.

If intelligence is a vast landscape, humans may occupy only a small, narrow ridge—an evolutionary compromise between problem-solving ability, energy efficiency, and social constraints. AI, free from those restrictions, could traverse cognitive terrain we can’t even imagine, accessing thoughts and experiences we can’t ever hope to understand, in the same ways ants can’t understand music. This seems very likely to be correct if humans are just one specific animal line that evolved via natural selection, rather than transcendent beings who the universe was made for.

It’s okay to put probabilities on speculative future events, but they often smuggle in a lot of unstated assumptions

Is a statement like “There’s a 70% chance that AI will surpass human intelligence by 2050” meaningful? This depends on what you think “a 70% chance” actually means.

The two most popular definitions of what probability means are frequentism and Bayesianism:

Frequentism: Probability is defined as the long-run frequency of an event occurring in repeated trials. For frequentists, “the probability of a coin landing heads is 50%” means that if you flip the coin an infinite number of times, about half of the flips will be heads. This definition works well for things that can be repeated many times under identical conditions, but can’t make sense of statements like “What’s the probability that AI surpasses human intelligence by 2050?” Since we can’t rerun history multiple times, frequentists would say this is a meaningless statement.

Bayesianism: Probability represents how rational it is for an observer to believe something. A probability of 50% for AI surpassing human intelligence by 2050 means that, given everything we know right now, believing that AI will surpass human intelligence by 2050 is exactly as rational as believing that a fair coin will land heads-up. Bayesians can put probabilities on any belief, because it’s a measurement of how rational it is to believe it based on the evidence you have, not on how many times an event would occur in a lot of repeated trials. “I think the odds of God existing are 10%” is something a Bayesian can say, but not a frequentist.

Bayesianism seems correct to me, and under Bayesianism, you can put a probability on anything, even things that are impossible to repeat. Instead of treating probability as an objective fact about the world, Bayesianism treats it as a measure of uncertainty, which makes it much more flexible.

So it’s okay in principle to put a probability on a speculative future event. I put the odds of nuclear war in 2025 as below 1%. This means I think it is more rational to expect a 100-sided die to land on 1 than it would be to expect nuclear war between now and December 31st, 2025. I think this makes sense and is defensible as a belief, in the same way I think it’s defensible to say that it seems more likely than within my lifetime AI will surpass humans at all economically useful cognitive tasks.

Working out very specific probabilities of future events can lead to a lot of unwarranted confidence, so I try to avoid making anything I believe about AI too specific. I could put specific numbers on different wild claims about AI. This would be allowed under Bayesianism, because probabilities just express your personal beliefs and uncertainties and how rational you think something is likely to be to believe.

AI that can do all human cognitive labor developed in my lifetime: 50%

Most or all of humanity experiencing permanent technological unemployment due to AI in my lifetime: 40%

Human extinction due to AI: 1-5%

These numbers feel cool and neat to write, but I’m just some guy. I don’t know a lot about what I’m describing here. Under Bayesianism, it’s fine to assign probabilities to things I know very little about, as long as I update them when new evidence emerges. These numbers simply reflect my current vague expectations. Given the many unknown unknowns, I expect my estimates to shift significantly over time. Because they’re so fluid, it wouldn’t make sense to base important decisions on them right now. I’ve noticed that people sometimes assign precise probabilities to future events, then forget how uncertain those estimates are—treating them as definitive rather than rough guesses with large error bars. This can lead to an unjustifiable level of certainty about something I don’t think it makes sense to be certain about. I disagreed with some points made in this post by AI Snake Oil on putting probabilities on speculative events, but I agree with the overall takeaway that most very specific probabilities people give to massively speculative AI risks are too specific and are smuggling in unjustified levels of certainty. If your range of AI causing permanent technological unemployment is between 20% - 99%, I think that’s reasonable and high enough to act, but if your probability is specifically 67.253% I suspect you’re just playing pretend and imagining you can have a clearer understanding of the future than is actually possible.

A note to people who know a lot about Bayesian epistemology, who I know are reading: I know there’s a lot more to this! I’m writing this for a general audience. This is more of a general warning against using numbers to trick yourself into certainty rather than a deeper claim about how probability works. I’m aware of what I’m getting wrong. For anyone who does want the full deep-dive, you should start here.

We shouldn’t rely too much on philosophical arguments to predict specifics about the future

Philosophy has been somewhat bad in the past at predicting what is going to happen in the future. In the 19th century there were extremely convincing philosophical arguments for the idea that the universe was determinate and that truly random events didn’t happen. In the 20th century, Bell’s Theorem demonstrated that at the quantum level true randomness does in fact occur.

Very specific thought experiments that claim to discover universal laws of history are pretty suspect and haven’t done a great job. I once had someone tell me that we should trust the average philosophical argument less than a one-off randomized control trial in developmental economics. It’s hard not to agree.

Philosophical anti-humanism is underrated

Critical theory at its best is the examination of unquestioned social, material, and ideological forces which are painted as natural backdrops to our day to day lives, with the goal of providing some means of collective liberation from oppressive assumptions and structures. While there’s a lot of critical theory I like, I’ve been disappointed with how theorists have approached AI. There are a lot of valid reasons to criticize AI’s current and future impact on people, but a lot of theorists go farther than this and paint all possible uses of AI as somehow lacking something fundamental that humans provide. A useful way to articulate my problem with this is describing humanism and anti-humanism in continental philosophy.

In continental philosophy, anti-humanism is the idea that humans are not the central reference point for knowledge, ethics, and social organization. The human subject is not a stable entity but is shaped, constrained, and constituted by language, social structures, history, and power relations. More simply: If you want to understand society and individuals, it is often a bad idea to defer to those specific individuals and their own first-person accounts that place themselves as rational actors creating their realities. The real “actors” in history might be ideology, or material flows, or class struggle, or markets, or natural processes, or complex interactions between all of them. Members of the anti-humanist canon would include Spinoza, Marx, Heidegger, Braudel, Foucault, Deleuze & Guattari, Latour, and Haraway.

I’m not really convinced by either humanism or anti-humanism, but I find that in a lot of conversations about AI a lot of people who spend time in the (in my opinion noble) attempt to deconstruct narratives of the human subject suddenly get extremely defensive of the human subject when AI shows up. If you read long critical theory texts on AI (a lot of what’s called AI ethics is often specifically critical theory) you immediately notice that AI is almost always framed as something incomplete, empty, or some generalized will to power, while the people interacting with it are infinite, deeply important, and have access to social and spiritual realms that the AI cannot ever access. This smells a lot like simple humanism to me. It makes sense to criticize specific aspects and uses of AI, but I’d like it if people were more open to ways that future AI tech could act as more of a neutral or even positive historical force complicating our sense of self and status in the world as free rational agents.

One of my favorite anti-humanists texts on technology is Donna Haraway’s A Cyborg Manifesto, on how human interaction with technology will over time rupture long-held illusions and false dichotomies of culture and nature, alienated and unalienated labor, and men and women. In some ways it evaporates into goofiness and becomes poetry, but it’s poetry I enjoy:

The cyborg is resolutely committed to partiality, irony, intimacy, and perversity. It is oppositional, utopian, and completely without innocence. No longer structured by the polarity of public and private, the cyborg defines a technological polis based partly on a revolution of social relations in the oikos, the household. Nature and culture are reworked; the one can no longer be the resource for appropriation or incorporation by the other. The relationships for forming wholes from parts, including those of polarity and hierarchical domination, are at issue in the cyborg world. Unlike the hopes of Frankenstein’s monster, the cyborg does not expect its father to save it through a restoration of the garden—that is, through the fabrication of a heterosexual mate, through its completion in a finished whole, a city and cosmos. The cyborg does not dream of community on the model of the organic family, this time without the oedipal project. The cyborg would not recognize the Garden of Eden; it is not made of mud and cannot dream of returning to dust. Perhaps that is why I want to see if cyborgs can subvert the apocalypse of returning to nuclear dust in the manic compulsion to name the Enemy. Cyborgs are not reverent; they do not re-member the cosmos. They are wary of holism, but needy for connection—they seem to have a natural feel for united-front politics, but without the vanguard party. The main trouble with cyborgs, of course, is that they are the illegitimate offspring of militarism and patriarchal capitalism, not to mention state socialism. But illegitimate offspring are often exceedingly unfaithful to their origins.

Another especially fun anti-humanist text is Spinoza Contra Phenomenology. This is like if Dennett wrote continental philosophy. The main theme of the book is a line of 20th rationalist continental philosophers who adopted a hyper-rational third-person perspective and opposed the more popular irrational first-person introspection of phenomenology. It’s goofy, but it could give you some useful language if you find yourself in conversations about AI where the other person is deploying a lot of simplistic continental humanist language and you’d like to complicate the conversation.

You don't need to assume physicalism for any of this. Epiphenomenalist dualists are obviously going to agree with physicalists about the the causal powers of artificial brains, and have good reason to also accept functionalism as a view of the "physical correlates of consciousness". (Plausibly even interactionist dualists should. There's just no obvious reason for *anyone* to endorse the parochial view on which only neurons can do the requisite generative work -- unless they hold a non-generative view of the mind, on which it doesn't even *come from* the brain, but is bestowed by God or something.)

Beneficentrism : Utilitarianism :: Non-parochialism : Physicalism

This is really great Andy. On a lot of this you're preaching to the choir with me, but even as a fan of functionalism/phil of language/bayesianism there was some new insight for me. I endorse Richard's point that you can get a lot of the first section without necessarily requiring physicalism.