AI and Folk Cartesianism - Part 1: Defining the Problem

Why I'm scared of linear algebra

“Let me see if I understand your thesis. You think we shouldn’t anthropomorphize people?” -Sidney Morgenbesser to BF Skinner

The 2020s have made my philosophy degree feel more worthwhile. Not only has social media made a ton of new people interested in philosophy, but the real world has also made many of the main questions in philosophy more relevant. AI especially has brought many philosophy topics into the mainstream, but it’s also polarized a lot of the debates. Back in 2011, I could say things like “The human mind is composed of natural processes, like everything else in the world, and therefore it could probably eventually be replicated by a machine, because in some sense it itself is a machine” and people would have long drawn-out conversations with me about whether that’s true or what that implies about language or experience or society. Now, when I say the same thing, it’s much more likely that I’ll get accused of “just buying into the recent AI hype” or that I’ve been tricked by secularism or capitalism or worse to deny the fundamental transcendent character of human minds. This issue used to be a pretty marginal question, but now it’s entered mainstream partisan debate. Sides have been taken.

What’s odd is that a lot of critics of the “minds are machines” view used to implicitly defend it. Back in the 2010s, there was a general worry about anthropocentrism. The belief that humans were in some way unique or separate from the natural world was regularly sneered at as “naive humanism” at best and a method of justifying exploitation of the natural world at worst. There was also a lot of talk about Cartesianism (the philosophy of René Descartes) as the origin of many of society’s problems. Specifically, mind-body dualism was accused of denigrating embodiment and elevating technocratic authoritarian reason. I always thought both criticisms went too far, but analytic philosophy had turned me into an anti-Cartesian naturalist, so I was able to nod along and contribute to these conversations where I could. Since then, attitudes toward Cartesianism have flipped. Many of the same people are now saying that AI cannot, by definition, ever have knowledge, because it does not have subjective first-person experience, or that it’s lacking some transcendent non-physical characteristic the human mind has; both implicitly Cartesian takes. Accusations of anthropocentrism have also been replaced with accusations of anthropomorphizing. A common line is that “everyone who actually knows how this technology works knows that it’s just linear algebra.1 The only people who believe it’s thinking are dummies who anthropomorphize it because it seems human.” I long for the 2010s when it was more common to hear people talk about a lot of different systems exhibiting some basic qualities of mind. I think back then people would be less likely to assume linear algebra couldn’t mimic some basic mental processes.

There’s a cluster of beliefs I associate with “folk Cartesianism” that even critics of Descartes often fall into. It’s incredibly common, to the point that people talk as if its implications are obvious without ever having directly thought about them before. I think this cluster of beliefs falls apart when you poke at it, and the fact that it’s implicit in so many debates about AI shows that it’s not being poked at enough. This post will be me poking at folk Cartesianism, and arguing for “anti-Cartesian naturalism” which is a widely-shared view among analytic philosophers of mind. Nothing I write here will be new or surprising to people knowledgeable about analytic philosophy. But I’ve been feeling the gulf between academic philosophy and mainstream discourse and want to contribute to building a bridge. This will be a long collection of the most popular and effective arguments for why folk Cartesianism is wrong, and how I think it’s harming the AI debate.

I have three goals here:

You can identify what folk Cartesianism is, and when people are thinking like folk Cartesians.

You come away no longer viewing folk Cartesianism as the obvious, common-sense view of the mind. You have a better understanding of the anti-Cartesian naturalist view, and philosophy of mind in general.

You are more open to the idea that machines can replicate what happens in human minds. That minds are not magical, inexplicable substances separate from nature.

I’ve written this partly as an instruction manual to my past self I wish I had when I was younger, as my personal crash course in philosophy of mind 101 as it relates to AI.

Some of these points will be taken from my other posts on the same ideas. The “Naturalism” section will be repetitive for people who have read those already.

Contents

I define folk Cartesianism as consisting of three common intuitions:

Part 2: Problems for Cartesianism

“There is a unified self that floats above mental processes and observes them”

“We know our own internal experience with complete certainty”

“The basis of all knowledge lies in our first-person subjective experience”

Part 3: Implications for AI

Definitions

Folk Cartesianism

René Descartes inaugurated modern philosophy by attempting to establish a way to reach ultimate truth completely dependent on reason alone (rather than religious revelation). To do this, he looked for a solid, undeniable foundational fact he could start at. Everything that followed would be equally certain. He famously attempted to doubt all his beliefs, and found that the one belief he couldn’t doubt is that he himself existed. “I think, therefore I am.” From here he reconstructs all his other beliefs by building an intellectual ladder, with his belief in himself as the foundation. The next step is a pretty weird proof of God, followed by concluding that God wouldn’t deceive us about the external world.

Descartes’ explicitly and implicitly put forward many more specific claims about the mind, and his overall account matches how many everyday people imagine their minds working. “Folk Cartesians” mostly haven’t read Descartes, but have been influenced by how he and the broader culture talk about mind. So when I talk about “Cartesianism” here, I mean a cluster of concepts that are popular in everyday folk theories of the mind, not necessarily what literal Cartesian philosophers believe.

There are three key features of Cartesianism that I want to deny, and that are relevant for current conversations about AI.

1. There is a unified self that floats above mental processes and observes them

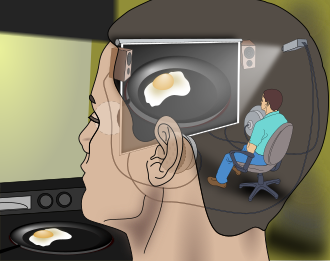

A “Cartesian ego” is a featureless observer hiding in the mind. This is the “I” in Descartes’ “I think therefore I am.” Cartesians imagine the mind as something like a movie on a screen, with the ego the silent observer. Critics call this the “Cartesian theater” model of the mind.

2. We know our own internal experience with complete certainty

Cartesians would say that we ourselves are egos. We observe our first-person experiences and thoughts. We have direct, clear access to them, in the way someone at a movie theater has access to the picture on the screen. The Cartesian ego also has direct, unmediated access to thought processes. We can turn our inner eye toward our thoughts in the way we would a piece of paper that lays out a step-by-step argument. We can observe the mental moves we’ve made and introspect on these thought patterns by just observing them directly. When we introspect, what’s happening is that we’re stepping back and observing the overall shape of our thought processes as they happen, like watching a line of dominos fall while standing above them.

3. The basis of all knowledge lies in our first-person subjective experience

Anything we could call real knowledge of the world has to come from the Cartesian ego observing and experiencing the world, or introspecting on its thought processes. A machine cannot have knowledge, for the same reason a line of dominos cannot have knowledge: there’s no Cartesian ego behind the scenes experiencing and judging the world. Thus, true artificial intelligence is impossible by definition, and many go farther and say AI is useless at what it’s trying to do. It can only ever imitate and copy knowledge. It cannot have knowledge of its own. It will always and only be glorified auto-complete. Even a machine that can handle and process large quantities of information cannot have knowledge, because the mind does more than information processing.

Many people apply this to our understanding of language as well. We only access the meaning of words via our first person subjective experience. I only know what “blue” or “tree” means because I have had subjective, first-person experiences of blue things and trees, and have learned to associate the words with those experiences. More complex concepts like “the national debt” are made up of simple concepts I’ve experienced like “money.” Any entity without a Cartesian ego cannot actually understand the meaning of words, because it cannot have these foundational experiences where it learns what words really mean.

Together, these three beliefs guide how many people think about their own minds, and how they think about AI. I will argue that they are incorrect.

The Cartesian view of the mind

The three of these paint an overall picture of the mind: a rich, internal theater where our egos live and experience things. Most of the important stuff that we consider “mind” happens here. Mathematical functions performed on our experiences and ideas happen a little behind the scenes, and we can perform those functions in our little theater as well (like when we hold numbers in our head while adding them together). Computers can replicate these mathematical functions, but they cannot replicate the internal theater. My goal for this post is to build some intuitions for the idea that this theater doesn’t exist. That we are not egos perceiving clear, unambiguous experiences, and that the mind is actually functions all the way down, where “function” is defined as any process that takes in inputs, performs computations on them, and gives an output.

Naturalism

Definition

I’m arguing for “anti-Cartesian naturalism.” Philosophical naturalism is a loose concept. It basically means “the world follows the laws of science, there is nothing magical happening.” Most analytic philosophers are naturalists, they just have strong disagreements about what counts as part of the natural world. There are three concepts associated with naturalism I adhere to in philosophy of mind:

Physicalism

Functionalism

Evolution

I’ll summarize and give some basic arguments for each.

Physicalism

Physicalism is the view that the only things that have causal effect on physical objects are other things described or used by the laws of physics. Physicalism could be said to mean “Ultimately, what exists is the universal wave function.”

For something nonphysical to have causal effect on physical entities would violate our current best theories of physics. Anything new that has causal effects is likely to be an entity similar to what physics is already describing. Physics has been remarkably successful at describing the world, and physicists operate under the assumption that anything influence physical objects will itself also be governed by physical law.

These are some qualities that all physical entities seem to share, and that differentiates them from supernatural entities:

Spatiotemporal location: Physical things exist in space and time. They have locations, durations, and can be detected at specific coordinates. Supernatural entities are often conceived as existing “outside” space and time.

Causal structure and lawfulness: Physical things behave according to regular, mathematical laws that describe their interactions. These laws are:

Discoverable through observation and experiment

Consistent and predictable

Expressible mathematically

Supernatural things are often defined by their ability to violate or transcend these laws.

Detectability/measurability: Physical things can be measured, either directly or through their causal effects. They leave empirical traces. Dark matter counts as physical even though we don’t know what it is, because we detect its gravitational effects.

Public accessibility: Physical phenomena are intersubjectively observable. Multiple people can measure and verify them using instruments. They’re not private or accessible only to special individuals.

There are entities in the universe we don’t understand, like dark matter and energy, but we should still expect those entities to conform to these 4 patterns when we eventually learn more about them. While physicalists believe that many more things “exist” besides fundamental particles and fields, those things are ultimately just names for those fundamental particles and fields interacting in some way. Even something as abstract as “the national debt” can in some sense be reduced to the incredibly complex behavior of the physical particles that make up people on Earth.

Functionalism

From the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy:

Functionalism in the philosophy of mind is the doctrine that what makes something a mental state of a particular type does not depend on its internal constitution, but rather on the way it functions, or the role it plays, in the system of which it is a part

Functionalism’s main claim is that mental states are defined by what they do, not what they’re made of. Among professional philosophers, functionalism is the most popular account of mental states.

A mathematical function takes an input and produces an output. Functionalists imagine mental states as being functions that take specific inputs and give outputs. A good example of something else like this is monetary value. “Twenty five cents’ worth of value” can exist in a quarter or a digital bank record of $0.25. What makes it the same monetary value is the function it plays in our broader system of exchange. When you transfer it to someone else, you can expect their behavior to be the same regardless of whether it’s delivered as a physical object or a digital exchange.

Similarly, the state of being in physical pain can happen in different animals with different physical brain structures, or even brains made of different physical substances, provided that their mental architecture reacts similarly (gives different outputs) to the same inputs. Just like the monetary value of twenty five cents can be instantiated in different physical systems (a metal coin or a computer), mental states as functions can also be instantiated in different physical objects.

If a system is able to reproduce all the same inputs and outputs as mental states as they occur in human minds, and is just made of different physical material, we should probably assume that it also has the same mental states as the human brain.

I don’t think current AI as it exists is conscious, but it is possible in principle for a machine made of silicon to be conscious like humans if it can reproduce the same inputs and outputs of our relevant mental states. It might be that at a certain level of complexity AI could also have mental states vastly alien to what humans can experience, but that we would still consider conscious experience.

An argument for functionalism, presuming physicalism

Suppose that we were able to replace exactly one neuron in my brain with a silicon chip that could send and receive exactly the same electrical impulses at exactly the same times as the neuron. Maybe there’s something about the substrate of silicon that prevents it from replacing all the functionality of a neuron, but let’s presume for now that it can send and receive all information the neuron receives. What would happen?

Importantly, if physicalism is true, nothing about my behavior would change. There wouldn’t be some immaterial soul or something similar swooping in to say “Hey, Andy’s brain has something strange in it. Something’s off!” The same electrical impulses would happen in my brain either way and cause me to behave in the same way. The same inputs would lead to the same outputs. If I looked at a tree and said, “I see a tree” before replacing a neuron with a chip, I would say the same afterward.

So if physicalism is true, my behavior would stay the same after my neuron is replaced with a chip. What would happen to my conscious experience of the world? Let’s imagine I’m staring at a tree (I’m using an example of my conscious experience of my field of vision because it’s easier to make an image). It seems like there are maybe 4 options, shown below:

Option 1: No change - My conscious experience of the world doesn’t change.

Option 2: A little missing - Maybe some small specific part of my field of vision or something similar goes blank.

Option 3: Less consciousness - There’s less conscious experience in general. Maybe my experiences are more blurry or dim, like I’m in a dark room.

Option 4: No consciousness - I no longer have conscious experiences.

We’ve established that my behavior wouldn’t change. Physicalism implies that the same inputs would lead to exactly the same outputs. This would make option 2, 3, and 4 very strange, because I wouldn’t react to my conscious experience changing, because my outward behavior would be exactly identical to the before case. If I looked out at a tree, and my conscious experience included a small piece of the picture missing, I would notice that and comment on it: “What’s going on? There’s a black dot in my field of vision.” If there were less conscious experience in general, I’d probably say “My vision is suddenly very blurry.” If there were no conscious experience, I’d say “Aaaah! I can’t see!” Because my behavior doesn’t change, I don’t say any of these things, I say “Look! A tree!” This would be very strange behavior if 2, 3, or 4 were true.

I trust my current self’s reports about his conscious experiences. My speech about my conscious experience matches the experiences I’m having. I should probably trust silicon neuron brain Andy’s reports as well.

Maybe it’s possible that my conscious experience would be disconnected somehow from my physical behavior, where I’d be helplessly losing consciousness as my physical body behaved normally as if it were a robot. Unconscious silicon brain Andy would take over as normal brain Andy helplessly lost consciousness and died. This would be very strange, because most of my day to day behavior is responding to my conscious experience. If you somehow removed my conscious experience’s ability to affect my physical behavior, I’d behave in very physically different ways, because I’d be missing a lot of important information. I wouldn’t react to heat or cold or anything in my field of vision. I might behave as if I were dead. It seems like it’s very likely that my conscious experience wouldn’t be affected by replacing 1 neuron with a silicon chip.

We could then go ahead and replace a second neuron with a silicon chip. For the same reason, my conscious experience wouldn’t change. We could build special chemical receptors and signals to replace other parts of my brain. As long as they had the same inputs and outputs on my behavior, I wouldn’t expect my conscious experience to change. At the end, I’d have the same mental states as before, but my brain would now be made mostly of silicon and other materials. This thought experiment is evidence that functionalism is correct: what makes something a mental state depends on its inputs and outputs, not on the specific physical material the system creating that mental state is made of.

So we’ve established that if physicalism is true, it seems likely whether my mind is in a certain conscious state is that the same inputs lead to the same outputs, not the internal constitution of what’s creating those inputs and outputs (a neuron vs. a silicon chip). Physicalism seems to imply functionalism.

Two other key ideas that together seem to imply functionalism:

The Neuron Doctrine: The idea that the brain is made of discrete cells (neurons) that communicate through connections. This supports functionalism because it suggests the brain works through information processing between units, not through some special physical substance. This is a central tenet of modern neuroscience.

The Church-Turing thesis: Any function that can be computed by any possible mechanical process can also be computed by a Turing machine. In other words, there’s a fundamental equivalence to all forms of computation. They’re all doing the “same thing” at a deep level.

If the mind is instantiated by a system of neurons taking inputs and sending outputs to each other (performing specific functions), and that this exact same type of thing can be instantiated in many different mediums, this seems to imply that everything we think of as mental can in principle happen in other systems that can perform computations.

It’s important to note that many non-physicalists are also functionalists, David Chalmers being the most famous example.

Evolution

If naturalism is true, the mind is a product of evolution. Like all other parts of all animals, the mind was subject to evolutionary pressures and natural selection. We should not expect that the mind came pre-made to access abstract truths about the world. Instead, for most of life’s history, minds mainly operated as machines to predict very local environments and specific situations, help the animal survive and reproduce, and (in more advanced brains) achieve and compete for social status (social status here being very broad, and including things like friendship and belonging). Given our evolutionary history, the real question is “Why do people believe true things?”

Dan Dennett had a great line about how “conscious human minds are more-or-less serial virtual machines implemented inefficiently on the parallel hardware that evolution has provided for us.” Put in more everyday language, our ability to do abstract reasoning, to follow a logical argument from premise to conclusion, to work through a math problem step-by-step, or to carefully consider the pros and cons of a decision, runs on top of brain hardware that wasn’t really designed for this kind of thinking.

Our brains evolved to handle dozens of things simultaneously: monitoring our surroundings for threats, maintaining balance, regulating body temperature, processing faces and voices, coordinating movement. This massively parallel processing is what kept our ancestors alive. In comparison, conscious, deliberate reasoning was rarely useful in the ancestral environment.

This helps explain why certain mental tasks feel so effortful. When you’re trying to hold multiple abstract ideas in your head at once, or forcing yourself to focus on something boring, you’re essentially running software that’s fighting against the grain of the hardware. Recognizing a friend’s face in a crowd or catching a ball requires vastly more computation, but feels effortless, because that’s what the parallel hardware excels at.

We shouldn’t expect our conscious minds to be perfectly rational machines, or to have some kind of magical access to higher realms of truth than what is available to other complex physical systems. We can obviously access truths that other systems can’t, but our access to these truths demands physical and evolutionary explanation.

I am aware that it is, crucially, not just linear algebra, and will talk about this more in part 3

I think articles like this are really important. Personally, I take a tack more akin to Schwitzgebel's, but maybe extended even a little further - I think our epistemic fog runs so deep, including in the present moment, that saying we "think" ai is or isn't conscious one way or another risks being an unacceptable smuggling in of our own conclusions - strongly risking a circularity that fails to do productive work, in order to stand as an alternative to what acts we might be beholden to under situations of full epistemic uncertainty.

Intriguingly, Dennett by the end of his career (and posthumously) warned harshly against AI as a profound epistemic threat that would establish "counterfeit" people. This has been completely perplexing to me - doesn't his own illusionism and framing of the intentional stance mean that marking "counterfeit" from "real" persons would imply the same metaphysics he'd reject? If the functional behavior already drives people to finding meaning, attachment, and value in ways that map anthropomorphically, if people can be driven to "AI psychosis" (I've read that clinicians are pushing back against this as a specific diagnosis), what is there to distinguish already?

It's becoming clear that with all the brain and consciousness theories out there, the proof will be in the pudding. By this I mean, can any particular theory be used to create a human adult level conscious machine. My bet is on the late Gerald Edelman's Extended Theory of Neuronal Group Selection. The lead group in robotics based on this theory is the Neurorobotics Lab at UC at Irvine. Dr. Edelman distinguished between primary consciousness, which came first in evolution, and that humans share with other conscious animals, and higher order consciousness, which came to only humans with the acquisition of language. A machine with only primary consciousness will probably have to come first.

What I find special about the TNGS is the Darwin series of automata created at the Neurosciences Institute by Dr. Edelman and his colleagues in the 1990's and 2000's. These machines perform in the real world, not in a restricted simulated world, and display convincing physical behavior indicative of higher psychological functions necessary for consciousness, such as perceptual categorization, memory, and learning. They are based on realistic models of the parts of the biological brain that the theory claims subserve these functions. The extended TNGS allows for the emergence of consciousness based only on further evolutionary development of the brain areas responsible for these functions, in a parsimonious way. No other research I've encountered is anywhere near as convincing.

I post because on almost every video and article about the brain and consciousness that I encounter, the attitude seems to be that we still know next to nothing about how the brain and consciousness work; that there's lots of data but no unifying theory. I believe the extended TNGS is that theory. My motivation is to keep that theory in front of the public. And obviously, I consider it the route to a truly conscious machine, primary and higher-order.

My advice to people who want to create a conscious machine is to seriously ground themselves in the extended TNGS and the Darwin automata first, and proceed from there, by applying to Jeff Krichmar's lab at UC Irvine, possibly. Dr. Edelman's roadmap to a conscious machine is at https://arxiv.org/abs/2105.10461, and here is a video of Jeff Krichmar talking about some of the Darwin automata, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=J7Uh9phc1Ow