More Perfect Union videos are wildly deceptive on data center water use

They're misinforming their huge audience and making the data center debate much worse

More Perfect Union (MPU) has become an influential voice in the data center debate. They have over 2 million subscribers and their videos get shared widely. Some even show local anti data center activists quoting other MPU videos in government meetings.

Unfortunately, MPU’s presentation of a few key data center issues is wildly deceptive. Viewers are left with a much worse understanding of the issue. Many millions of viewers are being tricked.

Here I’ll focus on a core false claim they reinforce over and over again: normal data center operations use so much water that they limit water access for regular people. They very regularly present locals saying this, here are some examples I gathered from different videos:

There is never any indication from MPU that American data center water usage has not raised the household cost of water at all anywhere, limited household water access in any way, or depleted local water supplies. Data centers aren’t using that much water. They behave like any other normal industry, and America overall is relatively good at water economics. In many areas, they actually significantly improve local water access by giving the utility enough revenue to make necessary upgrades. If you’re skeptical, you can read my deep dive on this here. The numbers are clear and straightforward.

I’ll run through a ton of examples of MPU being wildly deceptive on this. This is not just a selection of the worst clips, it’s almost all their presentations of data center water usage. I link to each full video so you can see if I’m taking anything out of context.

They key confusion MPU often relies on is that there have been a few places where the construction (not the operation) of new data centers has polluted local groundwater. The most prominent example is Meta’s large data center in Georgia, which seems to have added sediment to local groundwater and caused neighborhood wells to try up. This was the subject of this New York Times story, which many misunderstood to mean the data center itself used up water. These issues were all caused during construction. The data center hadn’t begun operations, and doesn’t draw groundwater. I have a breakdown here of ways the piece implied (incorrectly) that data center operations have raised water costs elsewhere. To be clear, Meta wronged these people, and stricter regulations should have prevented this, but it’s entirely a construction issue that could happen with any large building. It’s not an issue unique to data centers. There are very few other cases where water was polluted at all of the ~5,400 data centers in the US.

MPU videos edit together extreme false claims from locals about far-off data centers using water. This gives MPU themselves cover to push false ideas. They get to say “We’re just sharing what everyday people on the ground believe!” even though these people don’t have any experience with data centers themselves. At the end of this post, I share a long interaction I had with the head of MPU which seems to confirm this strategy.

Examples

A first example with a long deep dive on the claim

Take this clip from MPU’s coverage of a proposed AWS data center in Arizona:

This implies the Meta data center in Georgia didn’t just add sediment to nearby groundwater during its construction, its operational water use “bled the state dry.” The lead up to this clip is entirely about how much water the data center will use, not construction. This leaves the viewer with the impression that Georgia’s water access has been harmed by the normal operation of the data center.

But this is wrong! The data center in Georgia began operating in 2021. Since then, rates in the county have risen twice, both for unrelated reasons. In 2022, they rose due to economic issues caused by the pandemic making electricity and other inputs more expensive. Rates rose again in 2025, and again there are strong reasons to think this had nothing to do with Meta’s data centers:

Newton County expects an industrial wastewater reclamation facility to come online in 2026 which will on net reduce total industrial use of freshwater in the county. The county’s anticipating needing to provide less, not more, water to data centers, and yet the rate increased anyway.

There are no public connections anywhere between the rising rates and data center demand.

Most importantly, Meta’s data centers are only using ~2% of the county’s water. For comparison, a pharmaceutical manufacturing plant is using ~4% of the county’s water. A construction plant for Rivian cars is using about the same amount of water as Meta’s data center. In general, all counties in the US aim to keep industrial and household water markets separate from each other. Just like Rivian or the pharmaceutical plant only compete against other industrial buildings for water, the Meta data center is also only competing against other private businesses for water access.

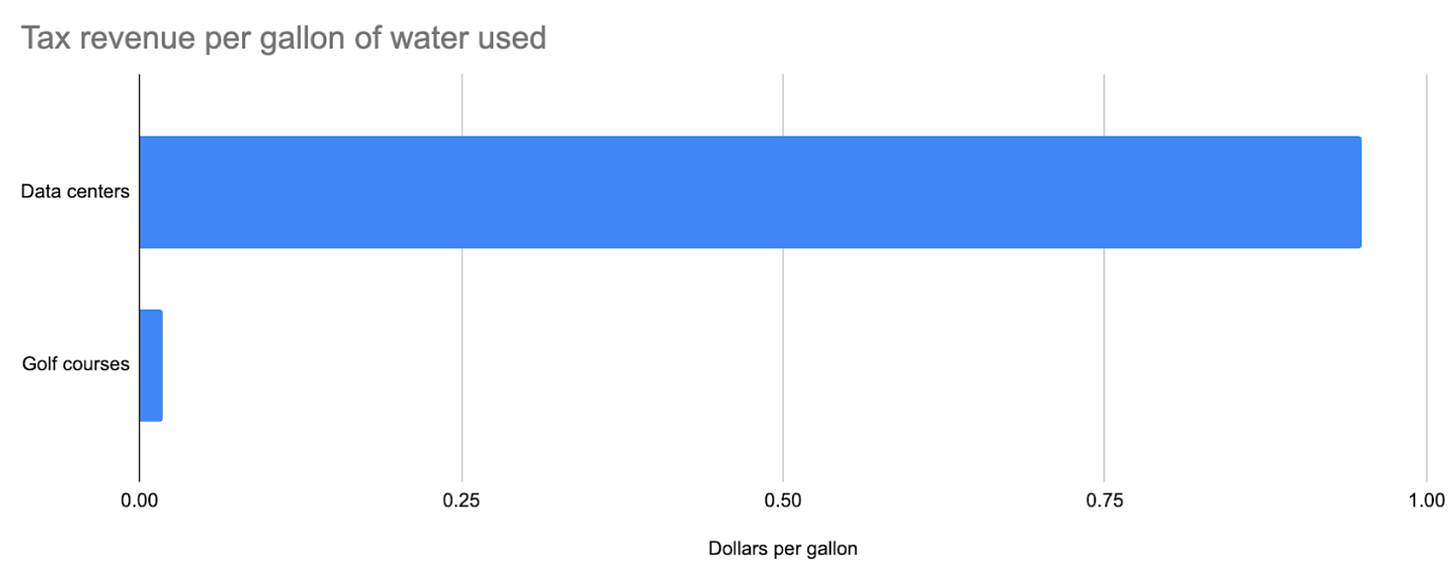

Of the main industries using water in Georgia, Meta’s data centers are providing way more tax revenue per unit water back to the local county. The county received ~$1,900,000 from Meta, ~$520,000 from Rivian, and ~$2,400,000 from the pharmaceutical factory1. Dividing by the water each industry uses, Meta provides $0.01 of tax revenue per gallon used, Rivian provides $0.005, and the pharmaceutical factory provides $0.009. In terms of tax revenue provided to the community, the data centers are the most water-efficient! You would not know this from watching this video.

This claim that the Meta data center “bled Georgia dry” is wildly false. Not only has Meta’s normal water use (or any other data center’s use) not harmed Georgia’s access to water, it’s actually given way more back in tax revenue per unit of water compared to most other industries. It’s the single most water efficient industry in the area if we just look at its tax revenue per gallon!

This claim is presented in this video without any question or pushback, and the activists saying it are very clearly framed as the good guys. The subtitles make sure to grab a “Busted!” jeer at the AWS representative from someone in the crowd. The viewer is left to conclude there’s some truth to the claim that the normal operation of the Meta data center harmed Georgia’s water access.

With this context, circle back and watch this full clip of the hearing (I’ve had this video skip to the hearing section). Think about what image this video paints in viewer’s minds about what’s happening in Georgia:

Let’s expand out to the general claim that data center operations harm local water access. Here are a bunch of individual places where MPU strongly implies data centers tend to harm local water access where they are built.

Many more examples

Keep in mind throughout all of these that there are no instances anywhere of data center operations raising water costs or limiting residents’ access to groundwater. Try to ask yourself what message viewers are taking from these videos, and whether they will leave open to the truth that data centers haven’t harmed water access. I’ve tried to be comprehensive and select most parts of their videos where they explicitly mention water usage, and what they say.

A common move is to share a contextless large number. For example, this tweet makes this sound like a huge amount of water:

7.2 million gallons per year! Sounds like a ton. How much is that? About as much as a small craft brewery. How worried should local residents of a county be about water use if they found out a new craft brewery were opening nearby? Probably not nearly as much as this tweet is trying to get across. This data center would represent about 0.02% of nearby El Paso’s water usage. MPU videos also regularly share large numbers like this to shock viewers who don’t know how much water everyday industries use.

This video description seems to strongly imply that the normal operation of the data center is causing water issues for a local community:

In the video itself, it’s made clear that this is another example of data center construction altering the water in a very specific community, not the normal operation of a data center. The company is not “using up the drinking water.” Throughout the whole video, the data center is still being constructed and not using water at all!

Next, this title:

For context, a million gallons of water per day is exactly as much water as the maximum normal demand of that pharmaceutical plant in Georgia. A single large Anheuser-Busch brewery in Fort Collins uses 2.5x as much water. The title frames this as if it would be a problem for the county’s water access, but it’s comparable to other normal industries’ water use.

In the video itself, a farmer worries about data centers using up all the local water, something that hasn’t happened anywhere in the country:

And later in the same video, the claim is made that this data center threatens the community’s water supply:

This is an odd framing. “Threatening a local community’s water supply” sounds like AI data centers are somehow more harmful than any other normal private industry. It’s hard to imagine the host saying something about a brewery or electric car factory “threatening community water.”

It may be that both of these examples actually exclusively mean “The construction of the data center might contaminate very local groundwater” but this is never made clear to the viewer, who is left to infer from the title that the main problem with the data center will be its “1 million gallons of water per day.” In reality, the normal operation of data centers has not “threatened community water supplies” anywhere.

The thumbnail on this next video definitely implies that data centers are limiting everyday people’s water access:

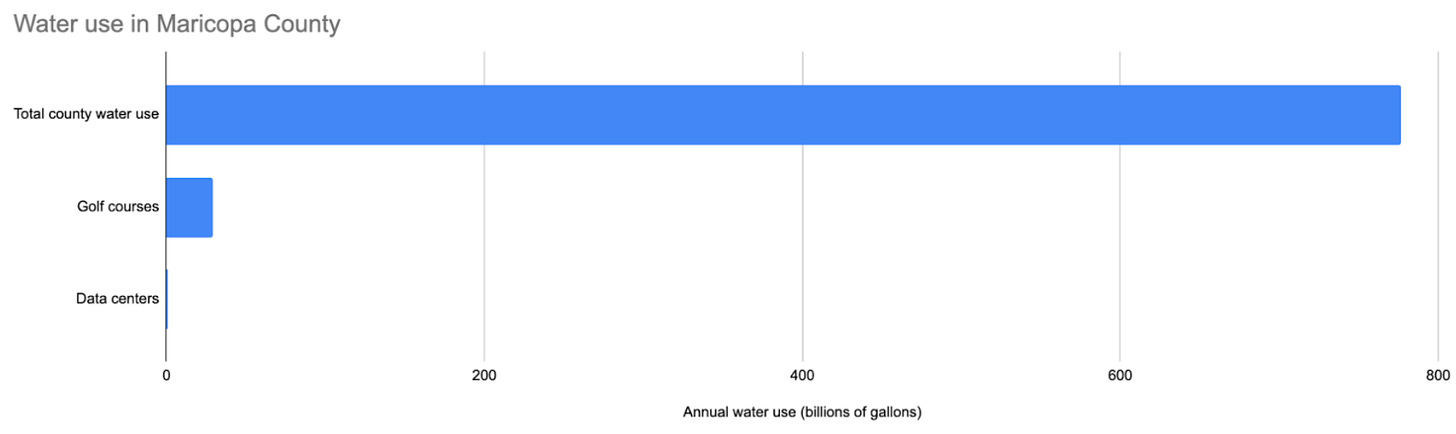

The title of this video is “Amazon’s Secret Plot to Build a Data Center in the Desert.” This seems to imply that data centers in deserts are shockingly bad. In reality, Arizona already has large numbers of data centers throughout the state. They collectively use about 1/50th as much water as just the golf courses in Arizona, but generate more tax revenue than the golf industry. Building data centers in the desert has been normal for a while and doesn’t harm water access. Here’s a comparison2 of water usage for data centers and golf courses in the county in Arizona with the most data water draw:

The introduction to this video (up to 0:25) implies that this will threaten water access:

And the longer interview with Victoria here does too:

The full video’s worth watching, it’s very deceptive throughout. It leaves you without an understanding that

Arizona already has a large booming data center industry.

All data centers in Arizona are using a tiny fraction of the state’s water use.

Water costs in Arizona haven’t risen at all due to data center demand.

Golf is using 50 times as much water as all data centers in Arizona, and providing way less local tax revenue.

Here’s a clip from a short here where they announce that a community won against big tech “trying to tap into the community’s water” as if this poses a problem, or is somehow different from all the other normal industries using way more water in Arizona:

Here’s a more blatant example of the interviewer fishing for an interviewee to share the water use angle. There are almost no examples of data centers polluting water at all, except for a few bad cases, one in Georgia and another in Indiana:

Here’s an example from this video where they have a local farmer share a concern about something that hasn’t happened anywhere, with zero pushback:

Here’s a six minute video called “Google threatens the water supplies of a drought stricken town"

The town this video is focused on, The Dalles in Oregon, is already the location with the highest percentage of water going to a local data center. 29% of all city water goes to a local Google data center. Water costs stayed flat until 2025, then rose a bit to fund a general upgrade to the water system. Some assumed this upgrade was purely to support the data center, but the city government responded to the question of whether the upgrade was motived by the data center with this:

No. The replacement of the water treatment plant and water transmission lines, the two largest and most expensive projects, are needed because the existing facilities are at the end of their useful life. It is now more expensive to rehabilitate and expand these facilities than it is to replace them. The water treatment plant is 75 years old and has experienced significant deterioration of its concrete structures. The water transmission pipelines, which are about 80 years old and made of unlined steel, are deteriorated and leaking. These projects would be needed even if the City did not have Google as a water customer.

The county used tax revenue from Google to fund the majority of the upgrade. They estimated that without the revenue from the data center, the cost of the upgrade would raise local water bills by 23%. Instead, households only paid 7.3% more for the upgrade. So in the place with the highest percentage of water going to data centers, the data center slightly lowered water bills.

You would not know any of this from watching this video. There’s a strong implication throughout that the data center is merely extracting water that people could otherwise use.

At one point in the video, one of the interviewees says “These corporations are the ones that need to pay something because they’re utilizing a resource and they’re not paying. But they’re keeping profits for their shareholders and themselves.” Google’s data centers in The Dalles provide more than 15% of the entire county’s tax revenue. The idea that they’re “not paying for the resources they’re using” is a lie.Separate from taxes, the Google data centers still pay normal utility bills for the water. If the local water utility decides that they are using too much, they can raise commercial water rates to reflect the scarcity of the resource. This is a common strange move in MPU presentation of data centers’ relationships to local governments. They talk as if the data center is not providing anything to the area, and the government has decided to allow it to come in and make everyone’s lives worse for no reason. In reality, there are usually a lot of benefits to a town’s public services in having a data center built, for the same reason towns are benefited by the presence of any other well-functioning private industry: they pay a lot in taxes, and the water utility gets a lot of additional revenue to fund upgrades.

The main water issue in American small towns isn’t the supply of water, it’s aging water infrastructure that doesn’t serve a large or rich enough tax base to get the money to upgrade. Old infrastructure makes water more expensive. It can also be dangerous (lead pipes etc.). Small town water costs are often higher, not lower, than cities, due to economies of scale. This wouldn’t happen if water costs simply rose when more water is used. Data centers moving into small towns often provide utilities with enough revenue to upgrade their old systems and make water more, not less, accessible for everyone else. The Dalles is a classic example of this dynamic playing out. Here are a few others:

Council Bluffs, Iowa: Google pays for expanded water treatment plant.

Quincy, Washington: Quincy and Microsoft built the Quincy Water Reuse Utility (QWRU) to recycle cooling water, reducing reliance on local potable groundwater; Microsoft contributed major funding (about $31 million) and guaranteed project financing via loans/bonds repaid through rates.

Goodyear, Arizona: In siting its data centers, Microsoft agreed to invest roughly $40–42 million to expand the city’s wastewater capacity.

Umatilla/Hermiston, Oregon:Working with local leaders, AWS helped set up pipelines and practices to reuse data-center cooling water for agriculture, returning up to ~96% of cooling water to local farmers at no charge.

What’s happening in a lot of areas like The Dalles is an otherwise poor community is having a very rich, well-run private industry move in, pay a ton of taxes, buy a lot from local water utilities. Not only can I not find any places where data centers raised water prices at all, there are lots of places where having a new big customer revitalized a poor community’s water delivery system. MPU leaves viewers with the sense that the opposite is happening.

There are no examples of MPU presenting the “data centers don’t harm local water access” side fairly

Every now and then MPU interviews someone who supports a data center build, but the editing makes it clear that they’re the bad guy in the video.

Here’s an example where the camera focuses a lot on a pro data center council member’s lavish house and personal water pool. The interviewer says among other things “This is a battle between tech billionaires and people - working class folks, who want to protect their water. Do you see this as a fair fight?” and later says “Supervisor Scott says he doesn’t think the people should be allowed to vote on this” and then the camera pans back to a chanting crowd. Funny enough, the clip opens with another org denying MPU an interview because they’re worried about biased media coverage. They’re right to be! MPU seems pretty biased here! It’s very funny that they cut straight from this note to a wildly biased interview where they make it clear to frame their subject as the bad guy.

Conclusion

It’s pretty easy to find a lot of examples where a viewer will leave an MPU video with a strong sense that data centers are limiting everyday people’s access to water, and that anyone saying otherwise is a shill for the AI companies, is actively lying to you, and ignoring the voices of everyday people on the ground. This sense of harm and guilt really cements the idea in viewers’ minds. In reality, this has not happened anywhere. One of the most popular sources of information about data centers online is giving people straightforwardly false ideas about how they work and affect local water supplies. Regardless of your opinions about other issues with data centers (pollution, electricity costs, or issues with AI more broadly) we should all agree that this is unacceptable for an outlet with such a large audience.

My run-in with the head of MPU

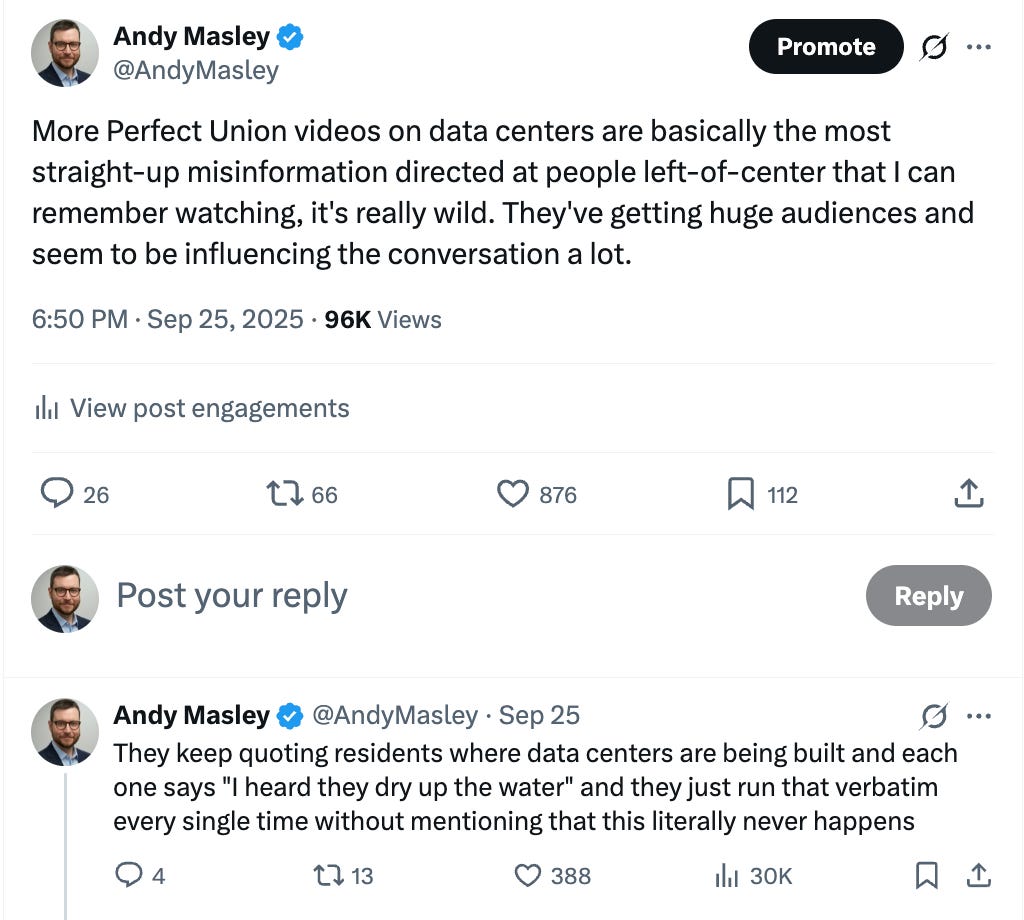

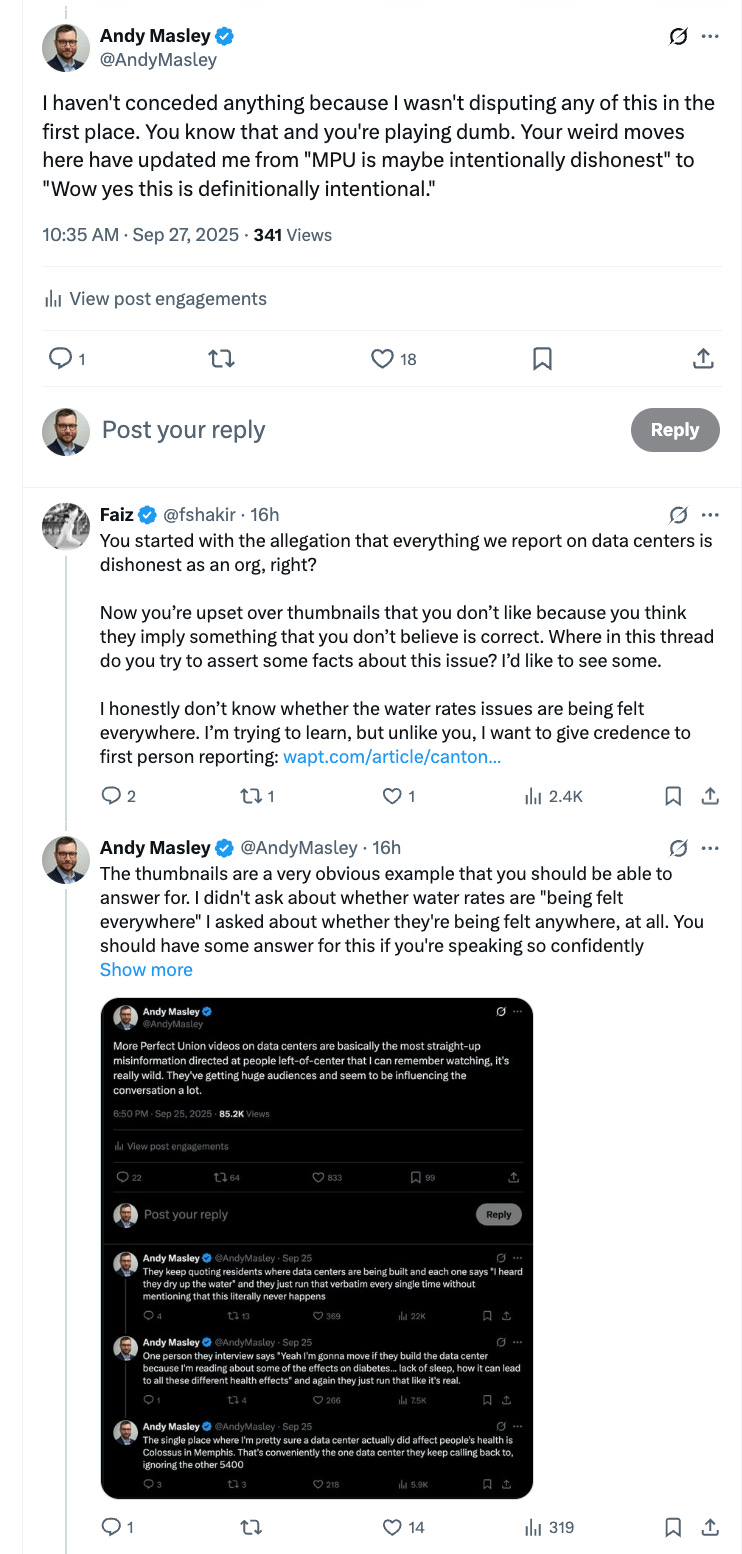

This will be a long account of a twitter spat I had with the director of MPU. I’m normally don’t want to mix Twitter drama with my blog, but MPU’s director’s bad behavior here led me to update pretty negatively on how MPU approaches simple facts. Most importantly, neither he, his staff, or any of his 100,000 followers could provide me with an example of where normal data center operations limited water access at all.

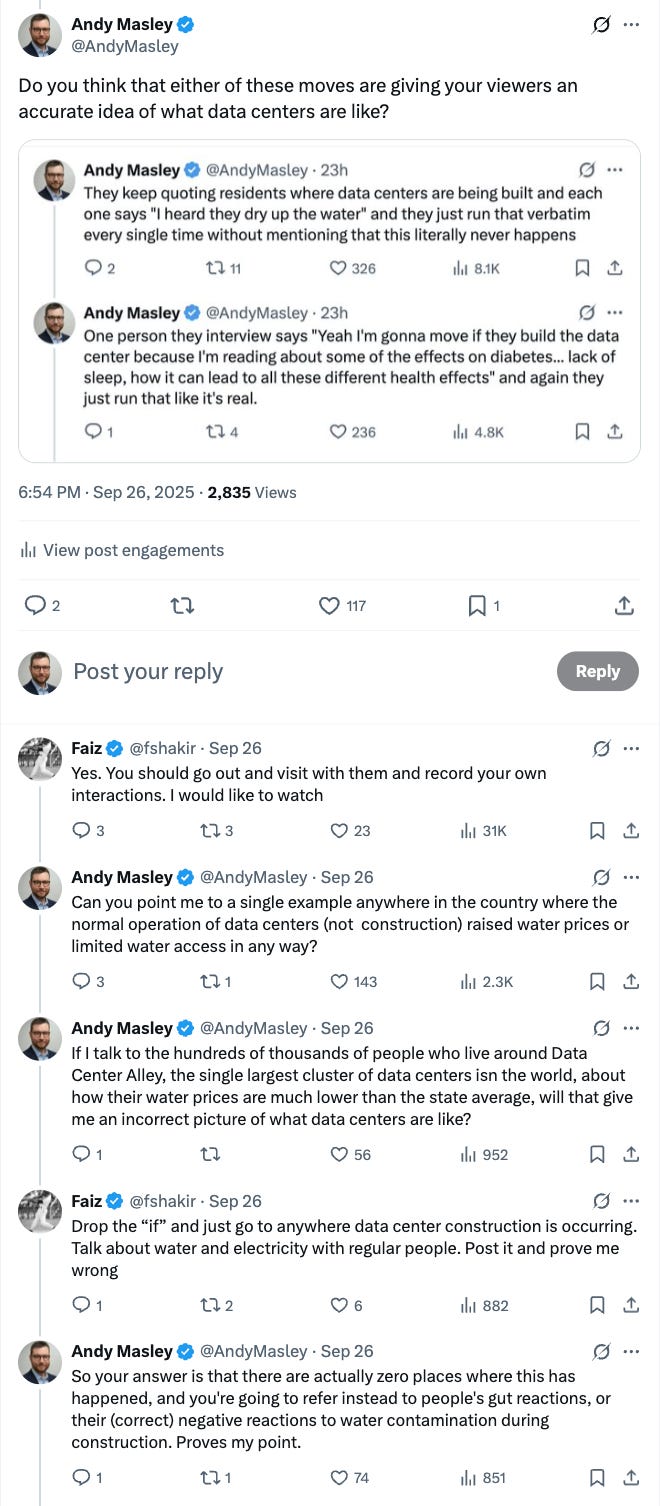

It started when I posted this:

The director of MPU quoted it with this:

I felt pretty confident that I was correct here, so I replied, and it led to this exchange:

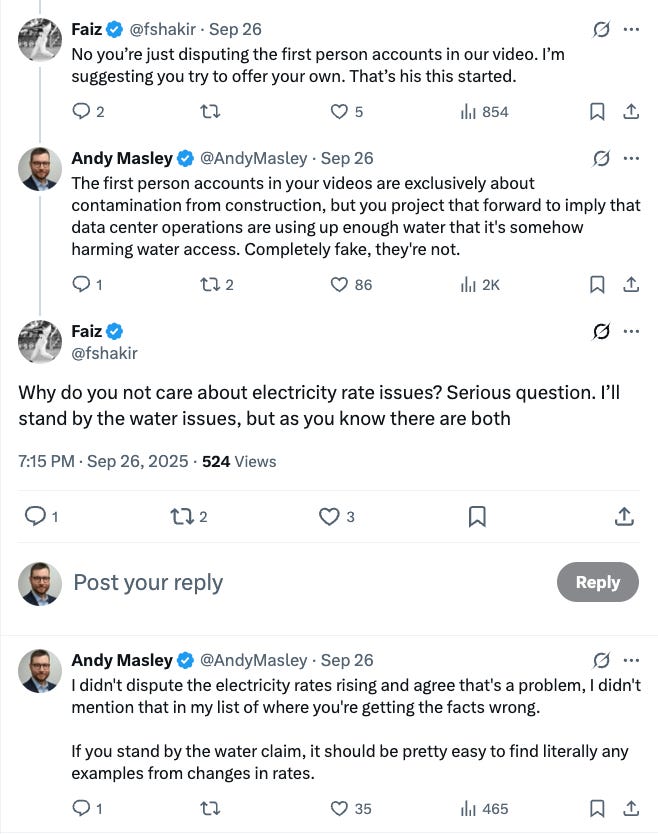

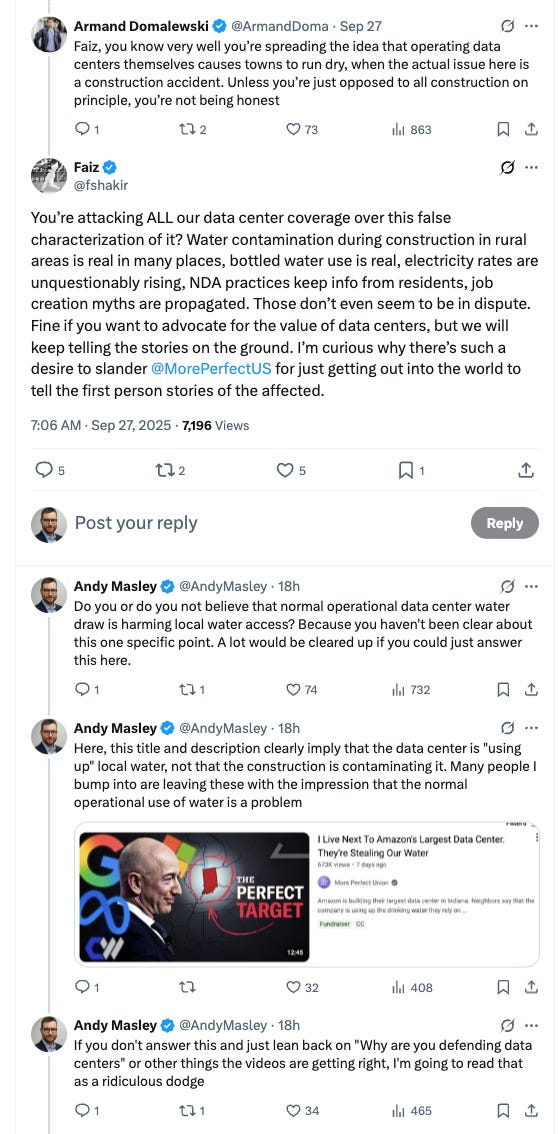

This was the end of this thread. Faiz and I had a few other interactions, but he could never justify the widespread implications throughout MPU videos that data centers harm local water access. Here are a few other interactions we had:

Didn’t get an answer on that one. Faiz’s strategy here seems to be interviewing locals about their opinions of far-off data centers they’ve been misinformed about. The magic here is that MPU isn’t factually responsible for what locals say, so they can film people saying and implying anything that fits their narrative, and then get away with filling videos with false claims. MPU then gets to declare “Hey, we’re just showing what people are saying.” Further, they get to cast these false beliefs as coming from the voices of the oppressed, not their own directors and editors trying to push a very specific story.

Here’s an instance where he swooped in later, still dodging the central question of whether data centers have raised water prices at all, anywhere:

I’ve unfortunately come to the conclusion that MPU does not seem interested in the facts of this question, and are more excited about running with a general anti data center line that gets views, even if they actively mislead viewers about pretty important information. I think it’s a shame that they’re having such a big effect on the data center debate and would encourage people to look elsewhere for news and resources on AI data centers.

Two PILOT distributions in 2024: Newton got $1.125M (Apr) and $750k (Oct), each explicitly broken out by the county BOE/BOC/Fire. That totals $1.875M for 2024. The share formula here is Newton 37.5% of Meta’s PILOTs at Stanton Springs (South). In Q1-2025, JDA recorded $5M from Meta again, which would imply another ~$1.875M to Newton if the same split applies.

Rivian is paying $1.5M per year in PILOTs in the initial years. Stanton Springs North uses a different revenue-sharing: 5% to Social Circle, and the remaining 95% split Newton 36.625%, Walton 36.625%, Morgan 14.25%, Jasper 9.5%. Newton’s take = 0.95 × $1.5M × 36.625% = ~$521,906 each year at this stage. (Rivian’s payment schedule escalates in later years (e.g., a jump beginning year 7) so Newton’s share will grow accordingly.)

Walton County (the collecting county for Takeda) distributed $6,337,630.31 in 2024 taxes in March 2025 under the Stanton Springs South revenue-sharing (Newton 37.5%). Newton’s combined share = 37.5% × $6,337,630.31 = ~$2,376,611. For context, the prior year’s Takeda distribution (Mar-2024) totaled $5,494,412.55, which implied ~$2.06M to Newton. (Within Newton, money is split between the BOE and the County by their millage-rate proportions.)

Thank you for standing up for sanity and honesty. I'm really sorry you have to deal with dishonest fanatics

I tend to default to "mistake theory", or blame good ol' cognitive bias, but this is clearly just incredibly deceitful on the part of MPU.

I'm sure some of it is clicks-driven, but I'm also getting a sense of otherwise intelligent people gradually drifting into a parallel reality - one where all of AI is completely useless, always wrong, always lying, only has negative impacts, is morally compromised in every aspect, and not worth any amount of money or power, let alone precious water. To them, it's all bad, it all needs to go, and everything needs to reset to 2022.

And then they act like that goal is almost within reach, if only they can find one more magic argument that puts them over the top. And for some reason, they've settled on water (which, where I'm from, is managed more as a nuisance than a scarce resource, so I'm doubly confused why they'd pick this as their spearpoint argument).