Data centers don't harm water access at all anywhere in America

A lot of journalism on AI's water impacts is misleading

There has been a lot of concern about the environmental impacts of data centers on local communities. In the last year, you may have seen headlines like these:

Surely, this means data centers are a significant water issue for local communities?

To see if this is real, I’ll focus on a specific claim: data centers’ water demands raise the household costs of water where they are built. I won’t focus on commercial or industrial water prices1. I also won’t focus on electric costs, which sometimes do seem to rise, though not as much as people think, or pollution, which in specific cases seems pretty bad.

After investigating this a lot, I’ve come to the conclusion that data centers have not raised household water bills at all, anywhere. They are consuming a ridiculously tiny amount of the nation’s water. The evidence is surprisingly clear and simple, the whole story of how America deals with water is ridiculously interesting, and each headline above is wrong for simple, obvious reasons that I’ll explain. First I’ll go over the situation with AI and water, and then go into why these headlines are either drastically misleading or (in the case of the New York Times) a pretty straightforward lie. Stories like this are everywhere: a headline with a framing that makes it seem like AI is causing a water shortage, but when you look closer, the shortage always turns out to be caused by something else.

No city or town governments have reported that any residential increases in water prices have been caused by data centers. Obviously government reports may not tell the whole story. But no matter where I look for plausible places data centers would have raised residential water prices, I cannot find anything. Nowhere in the articles I screenshotted above is any evidence provided at all, either.

Contents

Assumptions

First, I’m going to assume the main reason people are worried about AI’s water use is its consumptive use of freshwater. “Consumptive use” = the total water it withdraws form a local ecosystem that it causes to leave that ecosystem, via evaporation. Water simply moving through the data center and being reused doesn’t count as “consumed” until it’s evaporated and creates demand to withdraw more water from a local system.

Some assumptions about numbers I’m making here:

The total consumptive use of freshwater in America every day is ~132 billion gallons.

The total consumptive use of freshwater from all America from data centers, with both the onsite and offsite (nearby power plant) use of water was 200-250 million gallons per day in 2023.2 This is 0.15-0.19% of America’s daily water consumption. We don’t have more updated numbers.

The total consumptive freshwater use for the average American lifestyle is ~420 gallons per day.3

I’ve had to really dig for a lot of the water statistics I’ve found here. There’s a good chance some of them are wrong. If you think they are, and have good sources with updated numbers, please let me know. I’ve tried my best to piece the picture together, but it remains pretty unclear.

Likely places data centers would have increased costs

Here are a few places I looked:

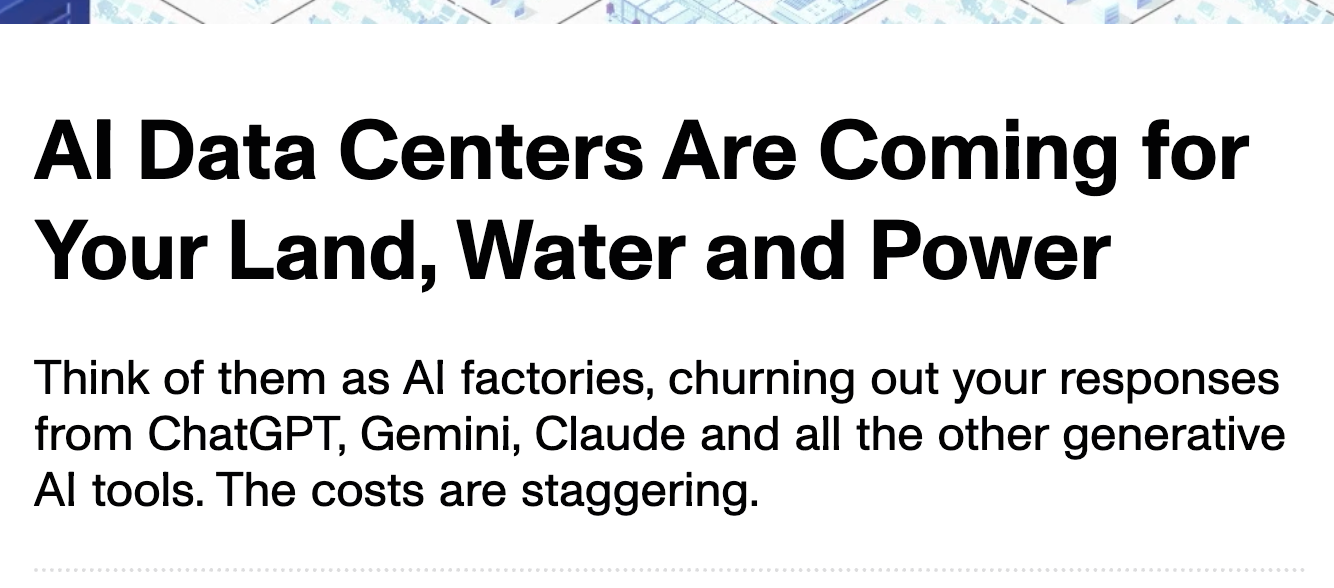

The county with the most data centers in the country

is Loudoun County, Virginia. It’s the home of “data center alley”: the largest concentration of data centers in the world. This link4 has the household water rates of every county in Virginia as of 2024. Loudoun’s water costs are pretty low by Virginia’s standards. It’s currently expecting a slight rate increase, but will still keep it low by state standards.

The city lists the causes of the rate increase:

A key element of providing clean drinking water and protecting the environment is ensuring that Loudoun Water’s infrastructure is maintained and in good working condition. This requires a significant capital investment every year. The proposed rate increases are primarily driven by:

Significant capital program (system replacement and expansion)

Actual cost escalation (ex., power and chemicals) is considerably higher than prior forecasting

Recent rate increases have been well below the cost increases mentioned above (rate increase for 2021, 2022 and 2023 were 3% annually)

Funding the repair and replacement reserve

Increases in purchased water, purchased sewer services and other operating costs.

It seems like a large part of the cost increase is coming from an infrastructure upgrade, but the county does also seem to be using more water. Is this because of the data centers, and is this causing part of the rise in household water costs?

Water for commercial vs. residential use is priced differently to keep markets separate, so while data centers could have indirectly contributed to the household cost, it’s likely that if the system wasn’t able to pump enough water, and household rates went up, water being more scarce for household use would have mainly been caused by other household water demand rising. From 2020-2025, Loudoun County’s population increased by 8%.

Loudoun County has a much more detailed report on rate increases. It lists the following reasons the rates have gone up:

Rising wholesale water purchase costs from nearby Fairfax County(+42% since 2021). Those increases are due to Fairfax Water’s own operating and capital expenses (PFAS treatment upgrades, chemical costs, inflation).

Rising wastewater treatment charges from DC Water (+36% since 2021). Driven by DC Water’s systemwide costs, not Loudoun’s data centers.

Spikes in power costs (+50%) and chemical costs (+40%). These are costs of running Loudoun’s plants. They rise with inflation, not with who’s buying the water.

Ongoing repair and replacement of aging infrastructure. This is the closest link to growth. Loudoun expands its system to meet all new demand: homes, businesses, and data centers. But the study is clear: growth-related expansion is funded through availability charges on new connections, not by existing household customers (“growth pays for growth”).

Capital improvements.

None of those listed drivers are attributed to data centers specifically. Data centers do appear in the report (as big reclaimed water users and as non-residential customers) but their costs are largely handled in separate rate categories and availability charges.

So this first one doesn’t really look like data centers made water costs go up. It makes sense. “Data center alley” has existed for a while, so the county’s already thought a lot about how to govern them.

The place where data centers use the highest percentage of local water

is Dalles City, Oregon, where 29% of all city water goes to a local Google data center. Water costs stayed flat until 2025, then rose a bit to fund a general upgrade to the water system. Some assumed this upgrade was purely to support the data center, but the city government responded to the question of whether the upgrade was motived by the data center with this:

No. The replacement of the water treatment plant and water transmission lines, the two largest and most expensive projects, are needed because the existing facilities are at the end of their useful life. It is now more expensive to rehabilitate and expand these facilities than it is to replace them. The water treatment plant is 75 years old and has experienced significant deterioration of its concrete structures. The water transmission pipelines, which are about 80 years old and made of unlined steel, are deteriorated and leaking. These projects would be needed even if the City did not have Google as a water customer.

The county used tax revenue from Google to fund the majority of the upgrade. They estimated that without the revenue from the data center, the cost of the upgrade would raise local water bills by 23%. Instead, households only paid 7.3% more for the upgrade. So in the place with the highest percentage of water going to data centers, the data center slightly lowered water bills.

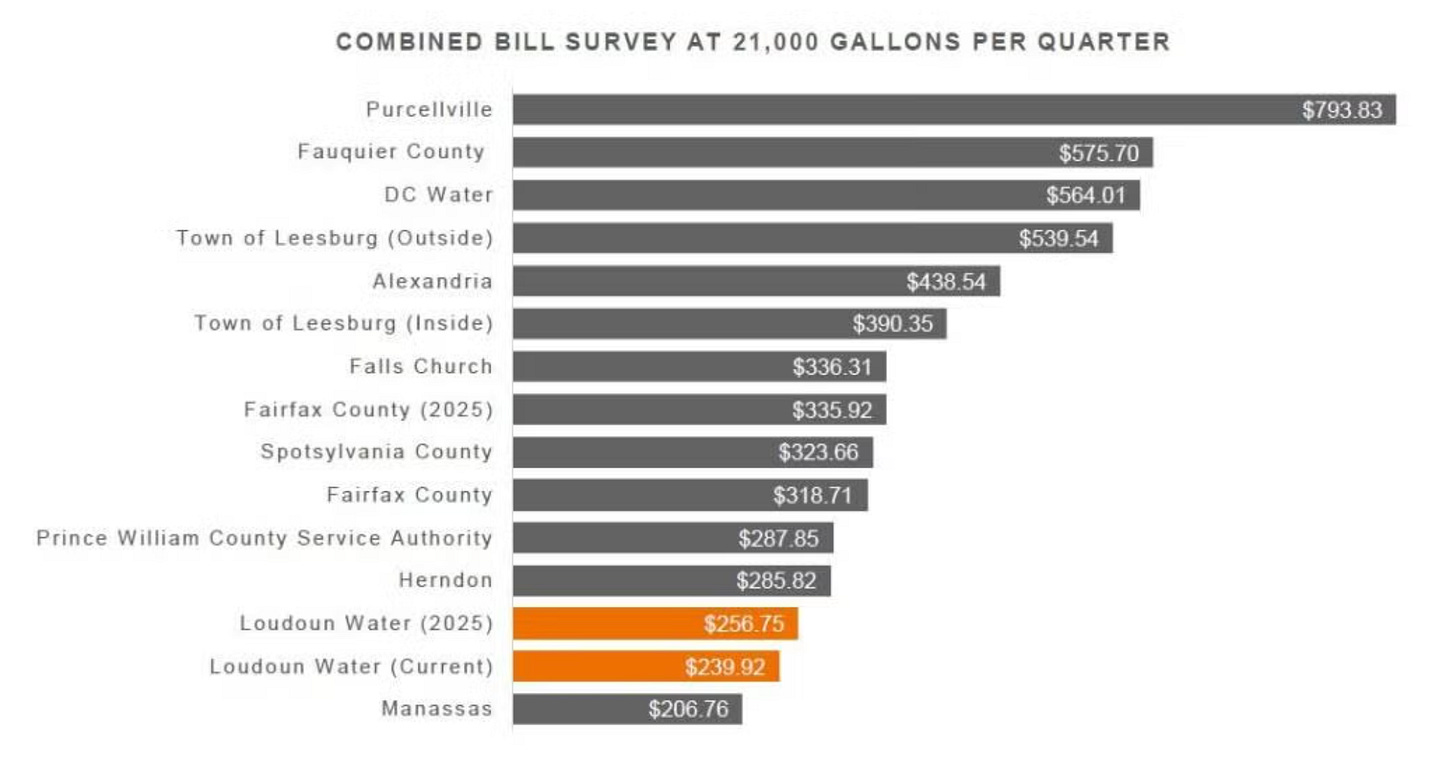

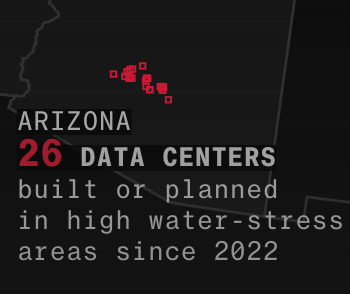

The county with the most water stress where data centers have been built

is Maricopa County in Arizona (home to Phoenix). The county is in extremely high baseline water stress (one of the highest in America), and has major data center builds (Google in Mesa; Microsoft in Goodyear).

Circle of Blue, a nonprofit research organization that seems generally trusted, estimates that data cneters in Maricopa County will use 905 million gallons of water in 2025. For context, Maricopa County golf courses use 29 billion gallons of water each year. In total, the county uses 2.13 billion gallons of water every day, or 777 billion gallons every year. Data centers make up 0.12% of the county’s water use. Golf courses make up 3.8%.

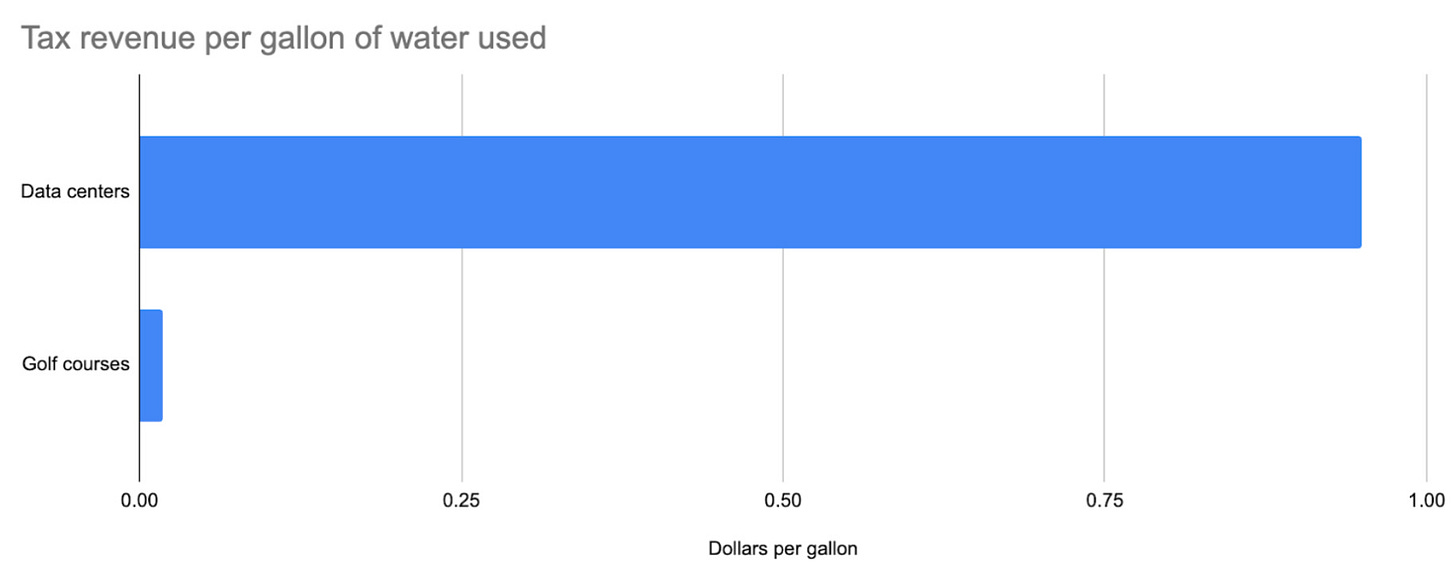

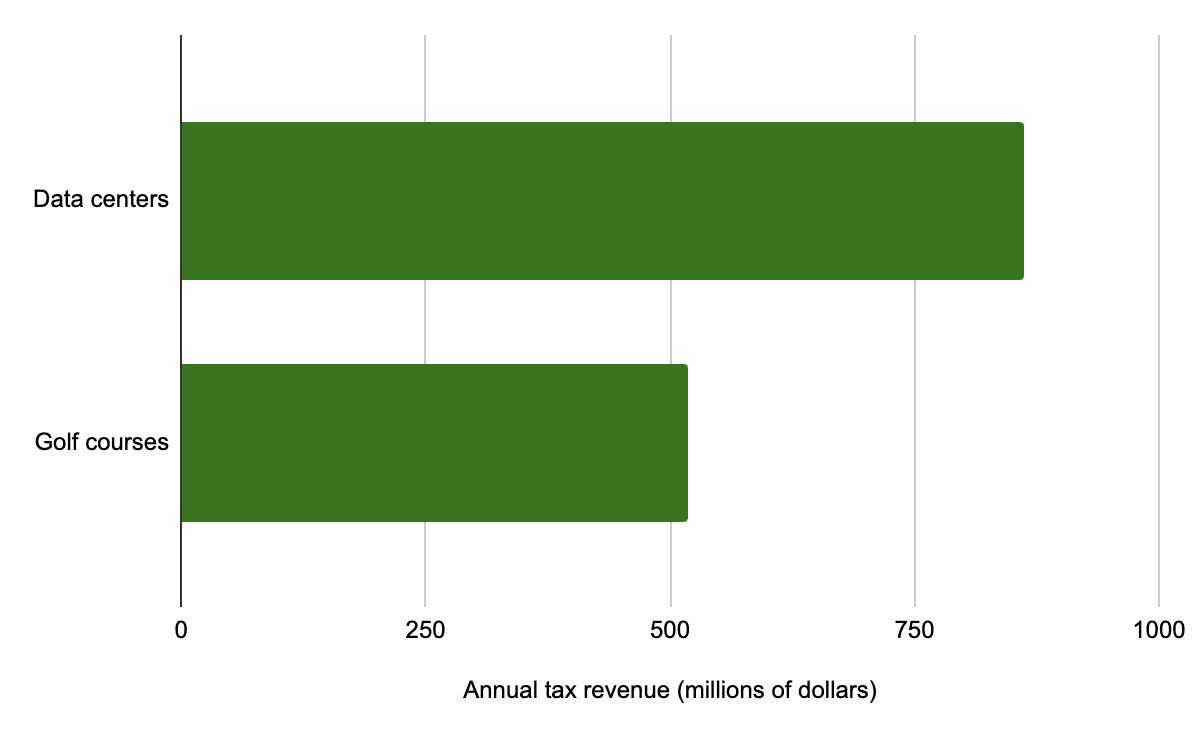

Data centers are so much more efficient with their water that they generate 50x as much tax revenue per unit of water used than golf courses in the county:

So even though data centers are using 30x less water than golf courses, they bring in more total tax revenue:3

Some people see this, and react with something like “Well I don’t think golf courses OR data centers should be built in the desert.” At some point this becomes an argument against anyone living in deserts in the first place. If you want to have a gigantic city in the desert, like Phoenix, that city needs some way of supporting itself with taxes, and giving jobs to the people who live there. Most industries use significant amounts of water. If Phoenix is going to exist, it’s going to need private industries built around it that are using some water. We have two options here:

Build industries that generate huge amounts of tax revenue relative to the water they use. Data centers fall into this category (though they don’t provide many jobs).

Do not build cities in the desert in the first place.

Arguments against data centers existing in the desert because they harm water systems there also often apply to building cities in the desert in the first place. It’s fine and consistent to say that Phoenix shouldn’t exist because it’s unnaturally pumping water from hundreds of miles away, but it’s inconsistent to say that Phoenix should exist, that its water bills should be kept as low as possible, but also that no industries that use any water should be built there.

Each year, it looks like water bills will become more expensive by an additional ~$180 over the full year. News organizations listed causes include inflation, infrastructure improvements, and the continuing drought as the main reason for rising water costs there. Technically, if the drought is responsible for higher water costs, then the data centers are responsible for some proportion of that, since they’re competing for the scarce resource of water. But because commercial and residential rates are different, data centers should only be raising the water costs of other businesses in the area.

Commercial buildings pay significantly higher rates for water in Maricopa County (and basically everywhere). Politicians in general know that voters get really really mad upset when costs rise, and so they want the markets for commercial vs. household water to be separate.

Let’s forget the commercial/residential split and assume all water use in the county is equally responsible for the cost increases, and there are no other causes of the cost increases at all (ignoring inflation and infrastructure projects).

If data centers are as responsible as their proportion of the grid, they be responsible for 20 cents of that increase over the year, or about 1.6 cents per month. This is the absolute worst increase that’s possible, assuming no rising water costs are due to infrastructure maintenance or upgrades, and the household/commercial split doesn’t exist.

Taxes on data centers raised $863 million each year for the state and local government in Arizona, so for every $0.20 cost all data centers impose on the county residents each year, they give back $115 to the state and local government in tax revenue. This seems like on net it’s definitely not sapping resources from the local community.

This is the most extreme example I can come up with, and it still seems to round to zero. I will concede that 20 cents per year for one of the most lucrative sources of tax revenue is technically a “nonzero” increase in household water costs. The numbers here are uncertain enough that this seems like it could be a place where data centers are impacting local water access, but with what we have right now seems like it rounds to zero.

Maricopa County noticeably has giant water parks:

This makes me think their water situation isn’t so dire that they need to be really careful with water rationing, and can probably afford a few more businesses using water.

The place with the highest concentration of very new data centers

… is Loudoun County again. There’s been a common framing that data centers are being built in poorer communities that don’t have the resources to resist them. This seems to be true in some places (xAI’s Colossus especially seems to be causing air pollution near poor communities in Memphis, but also isn’t affecting local water costs), but Loudoun County is the richest county per capita in the United States. I think that if the residents had significant objections to data centers being built nearby, they have the resources to coordinate stop them. The county government has an interesting FAQ on how they manage data centers.

So why aren’t household water costs rising anywhere?

Data centers are not using that much water

All U.S. data centers had a combined consumptive use of approximately 200–250 million gallons of freshwater daily in 2023. The U.S. withdraws approximately 132 billion gallons of freshwater daily. Data centers in the U.S. consumed approximately 0.2% of the nation’s freshwater in 2023. I repeat this point a lot, but Americans spend half their waking lives online. Everything we do online interacts with and uses energy and water in data centers. It’s kind of a miracle that something we spend 50% of our time using only consumes 0.2% of our water.

However, the water that was actually used onsite in data centers was only 50 million gallons per day, the rest was used to generate electricity offsite. Only 0.04% of America’s freshwater in 2023 was consumed inside data centers themselves. This is 3% of the water consumed by the American golf industry. Forecasts imply that American data center electricity usage could triple by 2030. Because water use is approximately proportionate to electricity usage, this implies data centers themselves may consume 150 million gallons of water per day onsite, 0.12% of America’s current freshwater use.

So the water all American data centers will consume onsite in 2030 is equivalent to:

The water usage of 260 square miles of irrigated corn farms, equivalent to 1% of America’s total irrigated corn.

The total projected onsite water consumption of all American data centers is incredibly small by the standards of other ways water is used.

In 2023 all data centers in America collectively consumed as much water as the lifestyles of the residents of Paterson, New Jersey. AI uses ~15% of energy in data centers globally. It seems unlikely AI in America specifically is even half of the water footprint of Paterson. If we just include the water used in data centers themselves, this drops to the water footprint of the population of Albany, New York.

Water economics

America is good at water economics. Our water management has a lot of ways to keep rates low for consumers. This (and AI’s very low total use of water) is the main reason it hasn’t affected water prices at all.

Household and commercial water prices are different everywhere to keep the markets separate so commercial buildings aren’t competing with homeowners. Data centers only compete with other businesses for water, like any other industry.

In low water scarcity areas, water isn’t zero sum. More people buying water doesn’t lead to higher prices, it gives the utility more money to spend on drawing more water and improve infrastructure. It’s the same reason grocery prices don’t go up when more people move to a town. More people shop at the grocery store, which allows the grocery store to invest more in getting food, and they make a profit they can use to upgrade other services, so on net more people buying from a store often makes food prices fall, not rise. Studies have found that utilities pumping more water, on average, causes prices to fall, not rise.

The only times water costs rise in low water stress areas when a large new consumer arrives is when the consumer demands so much water that utilities are forced to do major rapid upgrades to their systems, and the consumer doesn’t pay for those upgrades. In every example I can find of data centers requiring water system upgrades, the companies that own the data centers are the main source of revenue for the system upgrade.

The main water issue in American small towns isn’t the supply of water, it’s aging water infrastructure that doesn’t serve a large or rich enough tax base to get the money to upgrade. Old infrastructure makes water more expensive. It can also be dangerous (lead pipes etc.). Small town water costs are often higher, not lower, than cities, due to economies of scale. This wouldn’t happen if water costs simply rose when more water is used. Data centers moving into small towns often provide utilities with enough revenue to upgrade their old systems and make water more, not less, accessible for everyone else.

In high water scarcity areas, city and state leaders have already thought a lot about water management. They can regulate data centers the same ways they regulate any other industries. Here water is more zero sum, but data centers just end up raising the cost of water for other private businesses, not for homes. Data centers are subject to the economics of water in high scarcity areas, and often rely more on air cooling rather than water cooling because the ratio of electric costs to water costs is lower.

This seems fine if we think of data centers as any other industry. Lots of industries in America use water. AI is using a tiny fraction compared to most, and generating way, way more revenue per gallon of water consumed than most. Where water is scarce, AI data centers should be able to bid against other commercial and industrial businesses for it.

In general, if there’s a public resource like water, it’s considered the job of the utility and government to set rates to reflect its scarcity. Blaming a private business like a data center for using too much water seems kind of like blaming private customers for buying too much food from a grocery store. It’s the grocery store’s responsibility to set prices to reflect the relative scarcity of and demand for different products. If people are buying too much food from the store and there’s not enough money to restock, that’s the fault of the store, not the individuals. Private businesses shouldn’t be expected to monitor the exact state of local water to decide how much is ethical to buy from the utility. It’s the utility’s job to limit demand by setting prices higher if they actually think the company is going to harm the local water system. If utilities set prices high enough, data centers adjust by switching to different types of cooling systems that use less or no water. The market is (like in most places) the way that data centers receive information about the relative scarcity of water. In most conversations about AI and water, the responsibility for water management is oddly shifted to the private company in a way we don’t do for any other industry.

Politicians especially have strong motivations to keep household water prices low. Voters get mad when utility costs rise.

There are many cases of data centers being built, providing lots of tax revenue for the town and water utility, and the locals benefiting from improved water systems. Critics often read this as “buying off” local communities, but there are many instances where these water upgrades just would not have happened otherwise. It’s hard not to see it as a net improvement for the community. If you believe it’s possible for large companies using water to just make reasonable deals with local governments to mutually benefit, these all look like positive-sum trades for everyone involved.

Here are specific examples:

The Dalles, Oregon - Fees paid by Google fund essential upgrades to water system.

Council Bluffs, Iowa - Google pays for expanded water treatment plant.

Quincy, Washington - Quincy and Microsoft built the Quincy Water Reuse Utility (QWRU) to recycle cooling water, reducing reliance on local potable groundwater; Microsoft contributed major funding (about $31 million) and guaranteed project financing via loans/bonds repaid through rates. These improvements increase regional water resilience beyond the data center itself.

Goodyear, Arizona - In siting its data centers, Microsoft agreed to invest roughly $40–42 million to expand the city’s wastewater capacity—utility infrastructure the city highlights as part of the development agreement and that increases system capacity for the community.

Umatilla/Hermiston, Oregon - Working with local leaders, AWS helped stand up pipelines and practices to reuse data-center cooling water for agriculture, returning up to ~96% of cooling water to local farmers at no charge. That 96% is from AWS itself, not sure if it’s correct.

I could go on like this for a while. Maybe you think every one of these is some trick by big tech to buy off communities, but all I’m seeing here is an improvement in local water systems without any examples of equivalent harm elsewhere

In general, the US has a lot of freshwater.

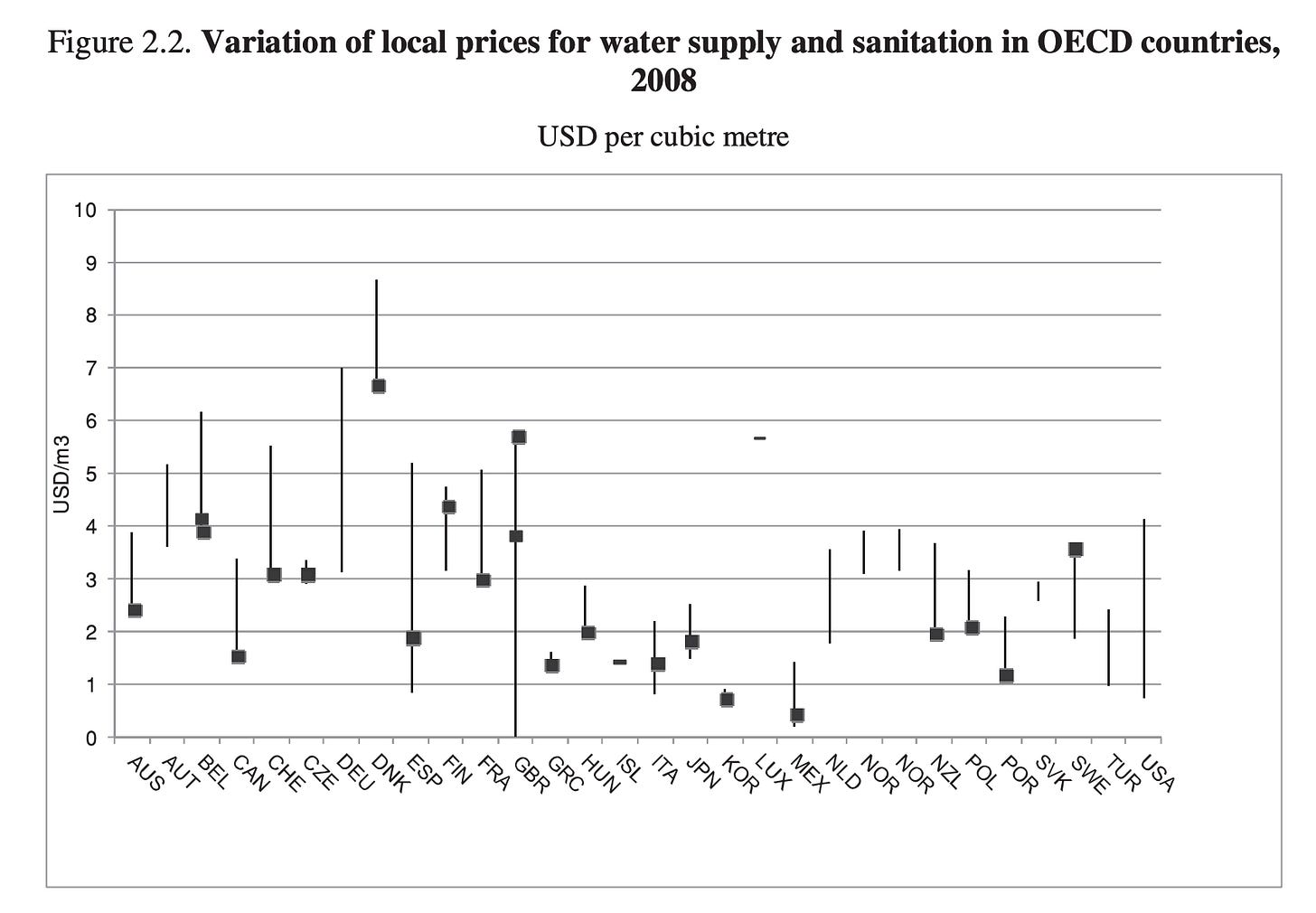

America has among the cheapest water costs of any nation in the world.

Because we’re also the richest nation in the world, our water costs are incredibly low as a percentage of per capita income.

It’s not that big of a deal that data centers require potable water

One concern about AI is that unlike a lot of the other industries I listed, it’s using potable water: water treated to reach specific quality standards, to the point that among other things it’s safe for people to drink. Crops basically never use potable water, in comparison. Maybe potable water is so much more valuable and rare that, even though AI isn’t using much, there’s not too much potable water anyway, so AI can still create a significant problem for water?

America’s total freshwater withdrawals are around 322 billion, of which 281 billion are freshwater. Of that, 40 billion is treated by water utilities until it’s at potable standards. That 40 billion is what consumers buy from local water utilities.

How difficult is it to turn those 241 billion gallons of non-potable freshwater potable? If it’s extremely easy, the difference doesn’t matter so much. It would be kind of like having money in two different checking accounts where it’s easy to move it back and forth, but saying we should worry a lot about one checking account being small regardless of the size of the other.

After looking into this, I’ve found that not only is it very easy to turn freshwater into potable drinking water, but also that a new large, consistent demand for treating freshwater into potable water drops the cost per unit of treating it, due to economies of scale. If any region has a lot of freshwater and little potable water, the best way to make potable water more available and cheaper is to introduce a new large buyer, which will give the local utility enough revenue to upgrade and expand their treatment facilities. Saying that my data is misleading because AI “only uses valuable potable water” actually gets the issue backwards: adding demand for more potable water in regions with lots of freshwater makes potable water cheaper and more abundant for everyone else per unit. The only place where it harms water access is where freshwater itself is scarce. The fact that AI only uses potable water actually helps my case that it’s not an issue for water access. The badness of AI water use is determined entirely by freshwater availability, not potable water availability, and in places where freshwater is plentiful, it usually makes potable water more available to everyone else.

To use a metaphor, imagine that freshwater supply in a region is like jewels in a mine, and potable water is like polished, carved jewels. We can imagine two cases:

There is a near infinite amount of jewels in the mine, but very few are being mined, polished, and carved.

There are not many jewels in the mine.

Imagine that demand for polished jewels suddenly skyrockets in each case.

In the first case, companies realize they can make a lot of money if they send a lot more miners in and build a lot of infrastructure to polish and carve the jewels. After a year, 100 times as many miners, carvers, and polishers are working to produce jewels. In this situation, would you expect the price of polished carved jewels to rise or fall? It seems obvious that here the price would fall, due to economies of scale. There are enough jewels in the mine that their supply doesn’t affect price, and all the revenue from jewel sales can be invested in more efficient systems of producing them. You would expect as a buyer to have to pay less and less for a jewel. In the same way, where freshwater is plentiful, treated water becomes less expensive as more people buy it.

In the second case, the supply of jewels in the mine drops off quickly. Raw, uncarved jewels become more and more expensive to obtain. Even if the cost of carving them is low, the total cost of the jewels will rise more and more due to the supply going down. Here, more demand for jewels causes the price to go up, but only because the raw jewels themselves are getting more expensive. In the same way, where freshwater is scarce, treated water becomes more expensive as more people buy it, but only because the freshwater itself is becoming more expensive and scarce.

So even before looking at the numbers, people complaining that AI requires precious rare drinking water are actually getting the issue completely backwards. This comes up very often. Karen Hao, who recently wrote Empire of AI, regularly emphases in interviews (and the book itself) that data centers are not just using water, but are “tapping directly into cities’ drinking water supplies.” Here’s a quote from a Democracy Now interview:

From a freshwater perspective, these data centers need to be trained on freshwater. They cannot be trained on any other type of water, because it can corrode the equipment, it can lead to bacterial growth. And most of the time, it actually taps directly into a public drinking water supply, because that is the infrastructure that has been laid to deliver this clean freshwater to different businesses, to different homes. And Bloomberg recently had an analysis where they looked at the expansion of these data centers around the world, and two-thirds of them are being placed in water-scarce areas. So they’re being placed in communities that do not have access to freshwater. So, it’s not just the total amount of freshwater that we need to be concerned about, but actually the distribution of this infrastructure around the world.

But it’s actually preferable for data centers to buy water from municipal water systems, because that means they’re paying into the system itself and providing utility revenue that on net benefit other buyers. It would be much worse if they weren’t using the municipal water system, because that would mean they would still be taking freshwater and competing with the municipal water system if the water were limited, but not providing any revenue to the utility.

So I think this on its own makes my case extremely strong that we need to look exclusively at the freshwater withdrawals being used on AI, not the potable water. The fact that data centers exclusively use potable water either doesn’t matter or helps my case. But let’s say this effect of economies of scale somehow doesn’t happen. What would this mean for AI?

How much do we actually pay to make water potable?

In the U.S., “potable” basically means “meets EPA’s National Primary Drinking Water Regulations”: a set of contaminant limits and required treatment techniques for things like microbes, nitrates, arsenic, and so on. EPA’s NPDWR table spells out the specific numerical limits. There’s nothing metaphysically special about this water. It’s normal freshwater that has gone through coagulation, filtration, disinfection, and sometimes a few extra polishing steps to hit those standards. EPA’s Surface Water Treatment Rules are written on the assumption that your source is an ordinary river, lake, or reservoir.

One way to see how cheap this conversion is is to look at what utilities already charge. EPA’s WaterSense program compiles national rate data and estimates that, in 2023, the average U.S. residential water price was about $6.64 per 1,000 gallons, with wastewater service adding another $8.57 per 1,000 gallons. Commercial customers paid about $5.56 for water and $6.86 for wastewater per 1,000 gallons. EPA summarizes these averages here.

That combined ~$15 per 1,000 gallons is not just the cost to flip freshwater into potable water. It also includes:

Treatment

Distribution pumping and storage

Maintaining and replacing pipes

Billing, customer service, and regulatory compliance

If you look at simpler wholesale or regional numbers, you get a cleaner sense of the underlying production cost. For example:

Ottawa County, Ohio reports that its regional water plant charges about $2.77 per 1,000 gallons to its distribution customers to pump raw lake water, treat it, and deliver finished water to local systems. That figure explicitly includes operations, maintenance, debt service, and admin. The county posts the breakdown on its FAQ page.

A Texas feasibility study for Brownsville’s conventional water treatment plant (separate from a proposed desal project) uses an internal treatment cost of about $1.34 per 1,000 gallons of potable water as the baseline. That appears in the Texas Water Development Board’s report tables.

These are “all-in” utility costs to take raw freshwater, treat it to drinking standards, and push it into the local system. They’re on the order of a couple of dollars per 1,000 gallons.

Nationally, EPA’s own example water bill assumes a retail volumetric charge of about $0.00295 per gallon, which is $2.95 per 1,000 gallons, for a typical surface-water system, and that again includes treatment plus distribution and overhead. EPA walks through that math in its “Understanding your water bill” example.

So as a very rough rule of thumb:

Turning raw freshwater into potable water plus delivering it is usually in the $2–$7 per 1,000 gallons range, depending on the city.

The incremental treatment-only cost (before pipes and billing) is typically well under a couple of dollars per 1,000 gallons, and often closer to $1.

How much potable water specifically will AI use? How much would it cost to make all that water potable?

The US public water supply uses ~40 billion gallons per day, all of this is potable. Data centers used 50 million gallons per day onsite in 2023. So their potable water usage was 0.13% of the public water supply. I want to beat the drum again that data centers more broadly are being used by all Americans for half their waking lives (because they support the internet), so the fact that as an industry they’re using a little bit of the total potable drinkable water in the country shouldn’t surprise us on its own. Assuming again that AI is ~20% of what happens in data centers (10 million gallons per day), AI in 2023 used ~0.03% of all drinkable water in America. If we assume an aggressive 10x growth of AI in data centers by 2030, and no changes to how it uses water, this will rise to 0.3%: 100 million gallons per day.

What about the water used offsite for power generation? This is often brought up as a “hidden” water cost of AI, and many estimates of AI’s total water use include it. This estimates often make AI’s total water use 5-10x bigger. However, effectively none of the water power plants use is potable. If you see an estimate of AI’s total water use, don’t immediately assume that all that water is drinkable. Check and see if the study is including the offsite water (they often do). If you’re worried about potable water specifically, only look at the water the data center itself is using.

Taking our estimate that making freshwater potable usually costs about $1 per thousand gallons, this implies that the US would be spending an additional $100,000 per day to generate enough potable water for AI data centers. If water markets and policies are working well, this cost should mainly be born by the AI companies themselves. This cost is about 0.01% of Google’s revenue alone. But let’s say that this doesn’t happen, and somehow the normal split between commercial and household rates breaks, and the cost is instead exclusively borne by American household consumers. How much would this increase water bills?

The average American family of four’s water bill is $2.60 per day. This implies American households spend in total $221,000,000 per day on water. The total increase in demand for potable water from data centers in the extreme case where they grow 10x by 2030, source all their water from municipal water systems, and the cost is somehow exclusively borne by households rather than AI companies and other commercial buyers, would together increase total American household spending on drinkable water by 0.04%.

Okay, well we know data centers aren’t evenly spread around the country. What if instead that 10x increase in water use happens exclusively in top 4 counties in the US with the most data centers are:

Loudoun County Virginia - population 446,530

Prince William County Virginia - population 484,625

Maricopa County Arizona - population 4,726,247

Licking County Ohio - population 180,311

The cost of turning enough additional water potable for data centers, if it were borne exclusively by the people living in these four counties, would increase their total spending on water by roughly 3% by 2030. This is the absolute most the cost of making freshwater potable could contribute people’s difficulty of accessing freshwater, under the insane assumptions that:

The 10x growth in AI activity will happen exclusively in 4 of America’s 3000 counties.

All costs of making more water potable are somehow only borne by households rather than companies.

The fact that AI requires potable water just isn’t an issue. The shocking headlines about AI “using up our precious drinking water” get the problem backwards. It’s good that we have new large buyers paying utilities to upgrade their water systems, because the main issue with water costs in America comes from the maintenance of old treatment and delivery systems that don’t have enough revenue to upgrade. People sometimes talk as if drinkable water is this incredibly rare naturally occurring thing that we stumble on, rather than something that we make. I blame Poland Spring ads.

AI as a normal industry

If a steel plant or college or amusement park were built in a small town, it would be normal for it to use a lot of the town’s water. We wouldn’t be shocked if the main industry in the town were using a sizable amount of the water there. If it provided a lot of tax revenue for the town and was not otherwise harming it, I think we would see this as a positive, and wouldn’t talk in an alarmed way about the specific percentages of the town’s water the industry was using. We should think of AI like we do any other industry. A data center drops into a town, draws water in the same way a factory or college would, the local system adapts to it quickly, and residents benefit from the tax revenue. The industry could provide enough water payments or tax revenue to improve the town’s water supplies in the first place.

In Texas, data centers paid an estimated $3.21 billion in taxes to state and local governments in 2024. There is no exact figure on total data center water use in Texas in 2024, but there are forecasts that they will use ~50 billion gallons of water in 2025. So excluding the price data centers pay for the water and energy they use, data centers are paying about $0.064 in tax revenue per gallon of water they use. The cost of water in Texas varies between $0.005 and $0.015 per gallon. Even if data centers caused water prices to quadruple, they would still ultimately be paying more back to local communities than the communities lost in additional water prices. This pattern holds everywhere data centers are built. They add huge amounts of tax revenue to local and state economies that seem to more than balance out any negative water externalities.

Many people have a strong aversion to use physical resource on digital systems, and think of any water spent on digital stuff as a waste. I think if we just looked passed the question of whether something is physical or digital and otherwise treated it as a normal industry, AI actually uses the least amount of water per dollar of revenue it generates.

Here are some other industries that use a lot of water, and their total revenue vs. how much water they use. I’ll measure this in dollars earned in revenue per thousands of gallons of water consumed. Here “onsite” means the water used in the data center itself, and “offsite” means the water used to generate the electricity at nearby power plants.5

Agriculture - $19.35/1000 gal

Electric power – $312.35/1000 gal

Data centers (onsite + offsite water) - $1,579/1000 gal

Bottled water - $1,703/1000 gal

Data centers (onsite water only) - $20,722/1000 gal

Why is journalism on AI water impacts so consistently bad?

Many negative news stories of AI’s water use are wildly misleading in very simple ways

I was motivated to write this after noticing that many long ominous articles on AI impacts on water never actually gave any evidence that local household water costs had risen anywhere. They were making a few other misleading choices as well.

Every popular article about how AI’s water use is bad for the environment in the last year has had a wildly misleading framing.

The Washington Post: Every email written using ChatGPT uses a whole bottle of water

This is the single most influential article ever written about ChatGPT and the environment. I still to this day regularly bump into people who think that ChatGPT uses a whole bottle of water every time you prompt it.

Friend of the blog SE Gyges has written the best thorough explanation of why this article looks likely to be an intentional lie. I’d recommend the entire thing. The article concludes that the only way this number could possibly be real is if you make every one of the following assumptions:

For a worst-case estimate using the paper’s assumptions, if

you query ChatGPT 10 times per email,

you include water used to generate electricity,

the datacenter hosting it is in the state of Washington,

the datacenter uses the public power grid or something close to it,

water evaporated from hydroelectric power reservoirs could otherwise have been used productively for something other than power generation,

and LLMs were not more efficient when they were being sold for profit in 2024 than they were in 2020 when they had never been used by the public

then it is true that an LLM uses up 500 or more milliliters of water per email.

You can reach a similar estimate by different methods, since they break out the water use per state differently. For example, if the datacenter hosting ChatGPT is not in Washington, it will have a higher carbon footprint but a lower water footprint and you will have to query it 30 or 50 times to use up an entire bottle of water. This is not what anyone imagines when they hear “write a 100-word email”.

That study’s authors are well aware that none of these assumptions are realistic. Information about how efficient LLMs are when they are served to users is publicly available. People do not generally query an LLM fifty times to write a one hundred word email.

It is completely normal to publish, in an academic context, a worst-case estimate based on limited information or to pick assumptions which make it easy to form an estimate. In this setting your audience has all the detail necessary to determine if your worst-case guess seems accurate, and how to use it well.

Publishing a pessimistic estimate that makes this many incorrect assumptions in a newspaper of record with no further detail is just lying to readers.

The Economic Times: Texans are showering less because of AI

Take this one from the Economic Times, it circulated a lot:

The article clarifies that this is 463 million gallons of water spread over 2 years, or 640,000 gallons of water per day. Texas consumes 13 billion gallons of waters per day. So all data centers added 0.005% to Texas’s water demands.

0.005% of Texas’s population is 1,600. Imagine a headline that said “1,600 people moved to Texas. Now, residents are being asked to take shorter showers.”

Many iterations of the same article appeared:

San Antonio data centers guzzled 463 million gallons of water as area faced drought

Data Centers in Texas Used 463 Million Gallons of Water, Residents Told to Take Shorter Showers

One article corrected for the much larger uptick of data centers in 2025:

50 billion gallons per year is a lot more! That’s more like 1.1% of Texas’s water use. Nowhere in this article does it share that proportion. It seems pretty normal for a state as large as Texas to have a 1% fluctuation in its water demand.

The New York Times: Data centers are guzzling up water and preventing home building

From the New York Times:

The subtitle says: “In the race to develop artificial intelligence, tech giants are building data centers that guzzle up water. That has led to problems for people who live nearby.”

Reading it, you would have to assume that the main data center in the story is guzzling up the local water in the way other data centers use water.

In the article, residents describe how their wells dried up because residue from the construction of the data center added sediment to the local water system. The data center had not been turned on yet. Water was not being used to cool the chips. This was a construction problem that could have happened with any large building. It had nothing to do with the data center draining the water to cool its chips. The data center was not even built to draw groundwater at all, it relies on the local municipal water system.

The residents were clearly wronged by Meta here and deserve compensation. But this is not an example of a data center’s water demand harming a local population. While the article itself is relatively clear on this, the subtitle says otherwise!

The rest of the article is also full of statistics that seem somewhat misleading when you look at them closely.

Water troubles similar to Newton County’s are also playing out in other data center hot spots, including Texas, Arizona, Louisiana and the United Arab Emirates. Around Phoenix, some homebuilders have paused construction because of droughts exacerbated by data centers.

The term “exacerbated” is doing a lot of work here. If there is a drought happening, and a data center is using literally any water, then in some very technical sense that data center is “exacerbating” the drought. But in no single one of these cases did data centers seem to actually raise the local cost of water at all. We already saw in Phoenix that data centers were only using 0.12% of the county water. It would be odd if that was what caused home builders to pause.

The article goes on with some ominous predictions about Georgia’s water use around the data center, but so far residents have not seen their water bills rise at all. We’re good at water economics! You wouldn’t know that at all from reading this article.

I think the main story being an issue with construction, but the title associating it with some issue specific to data centers, seems pretty similar to a news story reporting on loud sounds from construction of a building that happens to be a bank, and the title saying “Many banks are known for their incredible noise pollution. Some residents found out the hard way.” This would leave you with an incorrect understanding of banks.

Contra the subtitle, data centers “guzzling up water” in the sense of “using the water for cooling” has not led to any problems, anywhere, for the people who live nearby. The subtitle is a lie.

CNET’s long very vague report on AI and water

This same story was later referenced by a long article on AI water use at CNET, here with a wildly misleading framing:

The developer, 1778 Rich Pike, is hoping to build a 34-building data center campus on 1,000 acres that spans Clifton and Covington townships, according to Ejk and local reports. That 1,000 acres includes two watersheds, the Lehigh River and the Roaring Brook, Ejk says, adding that the developer’s attorney has said each building would have its own well to supply the water neededEverybody in Clifton is on a well, so the concern was the drain of their water aquifers, because if there’s that kind of demand for 34 more wells, you’re going to drain everybody’s wells,” Ejk says. “And then what do they do?”

Ejk, a retired school principal and former Clifton Township supervisor, says her top concerns regarding the data center campus include environmental factors, impacts on water quality or water depletion in the area, and negative effects on the residents who live there.

Her fears are in line with what others who live near data centers have reported experiencing. According to a New York Times article in July, after construction kicked off on a Meta data center in Social Circle, Georgia, neighbors said wells began to dry up, disrupting their water source.

There’s no mention anywhere in the article that the data center in Georgia was not using the well water for normal operations.

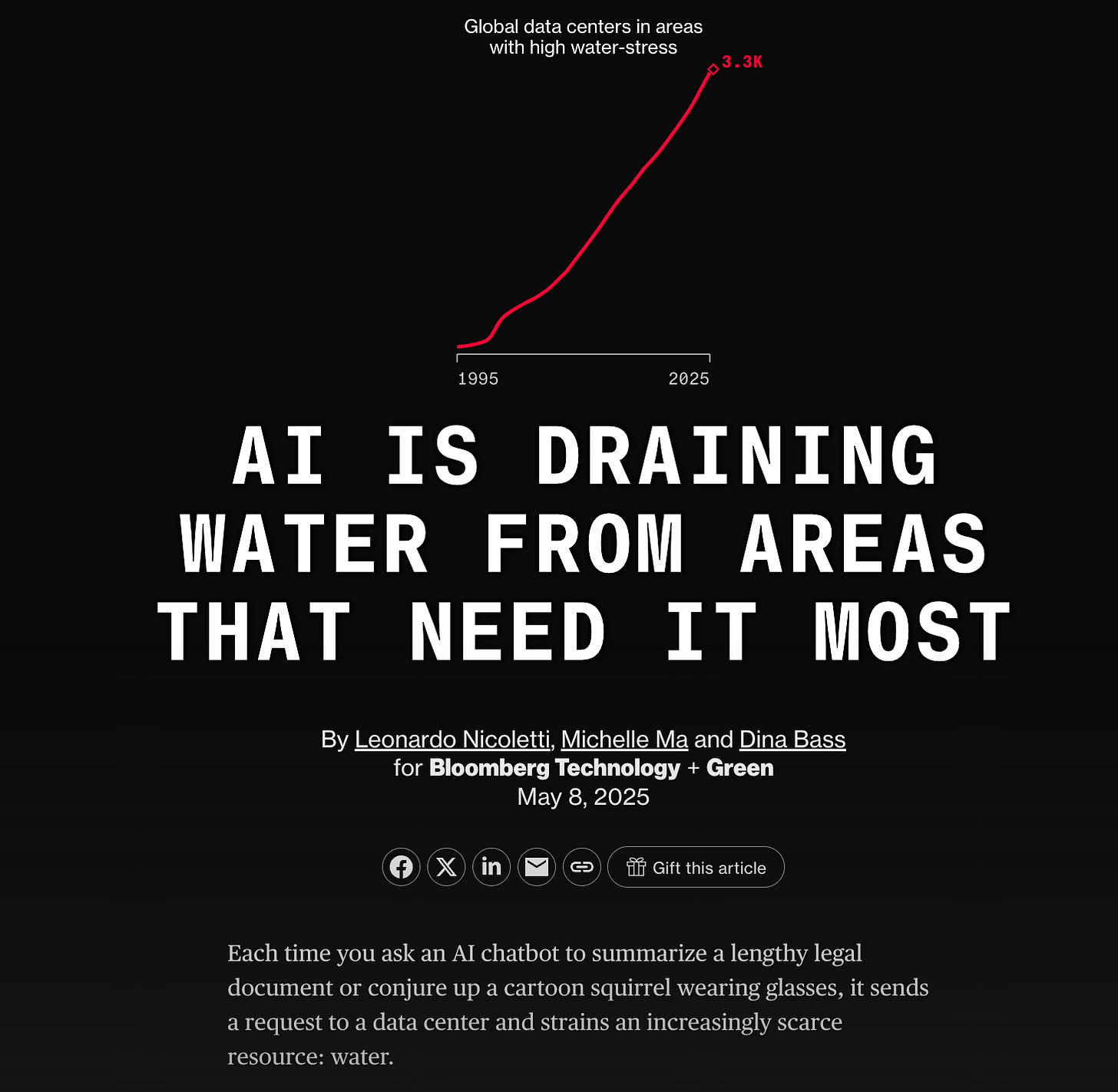

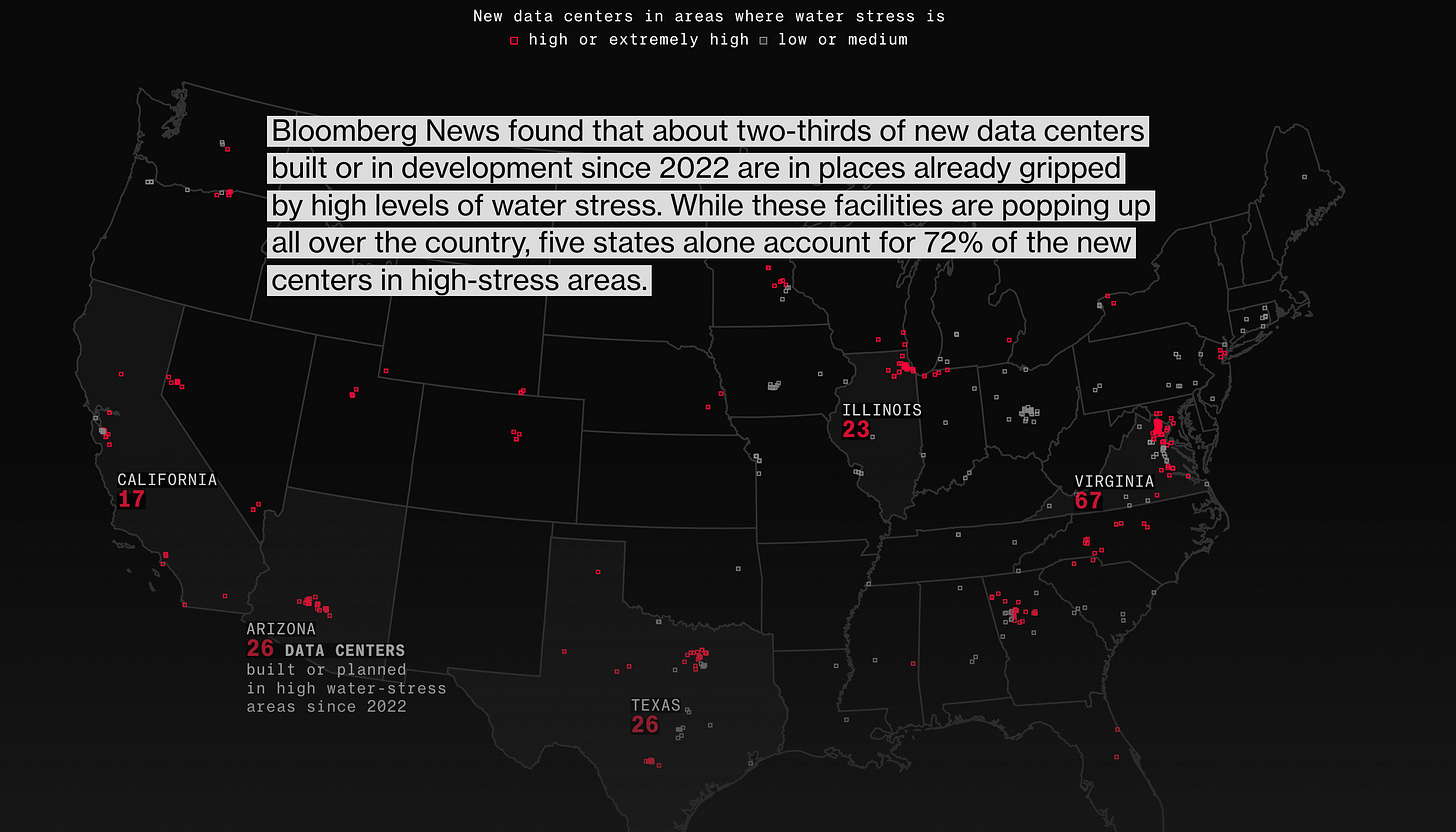

Bloomberg: AI is draining water from areas that need it most

Here’s a popular Bloomberg story from May. It shows this graphic:

Red dots indicate data centers built in areas with higher or extremely high water stress. My first thought as someone who lives in Washington DC was “Sorry, what?”

Northern Virginia is a high water stress area?

I cannot find any information online about Northern Virginia being a high water stress area. It seems to be considered low to medium. Correct me if I’m wrong. Best I could do was this quote from the Financial Times:

Virginia has suffered several record breaking dry-spells in recent years, as well as a “high impact” drought in 2023, according to the U.S. National Integrated Drought Information System. Much of the state, including the northern area where the four counties are located, is suffering from abnormally dry conditions, according to the U.S. Drought Monitor. But following recent rain, the Virginia Department of Environmental Quality on Friday lifted drought advisories across much of the state, though drought warnings and watches are still in effect for some regions.

Back to the map. There were some numbers shared in a related article by one of the same authors. But readers were left without a sense of proportion of what percentage of our water all these data centers are using.

AI’s total consumptive water use is equal to the water consumption of the lifestyles of everyone in Paterson, New Jersey. This graphic is effectively spreading the water costs of the population of Paterson across the whole country, and drawing a lot of scary red dots. The dots are each where a relatively tiny, tiny amount of water is being used, and they’re only red where the regions are struggling with water. This could be done with anything that uses water at all and doesn’t give you any useful information about how much of a problem they are for the region’s water access.

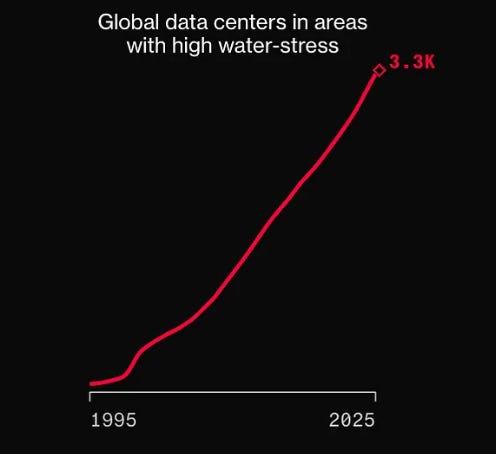

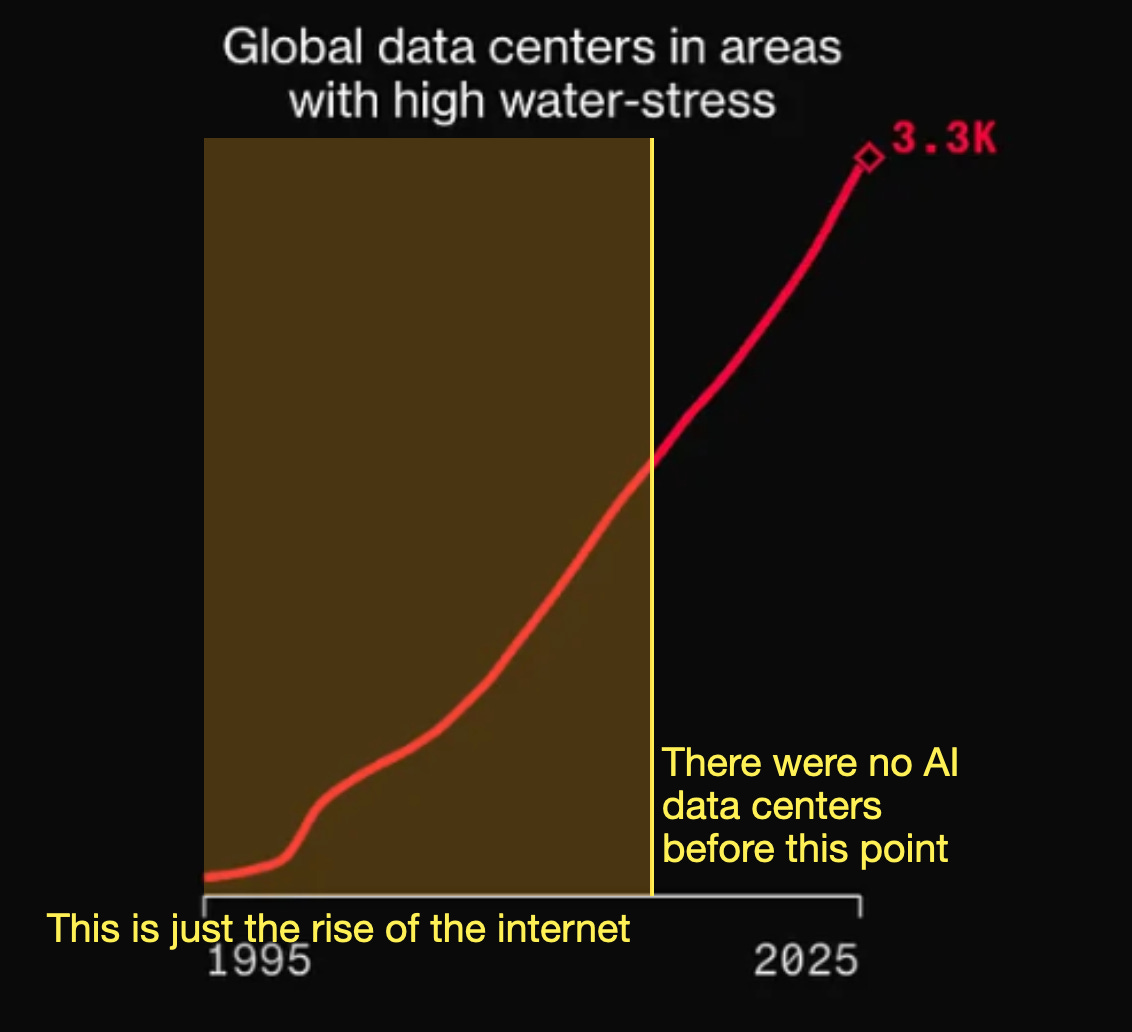

Even the title chart can send the wrong message.

I think for a lot of people, stories about AI are their first time hearing about data centers. But the vast majority of data centers exist to support the internet in general, not AI.

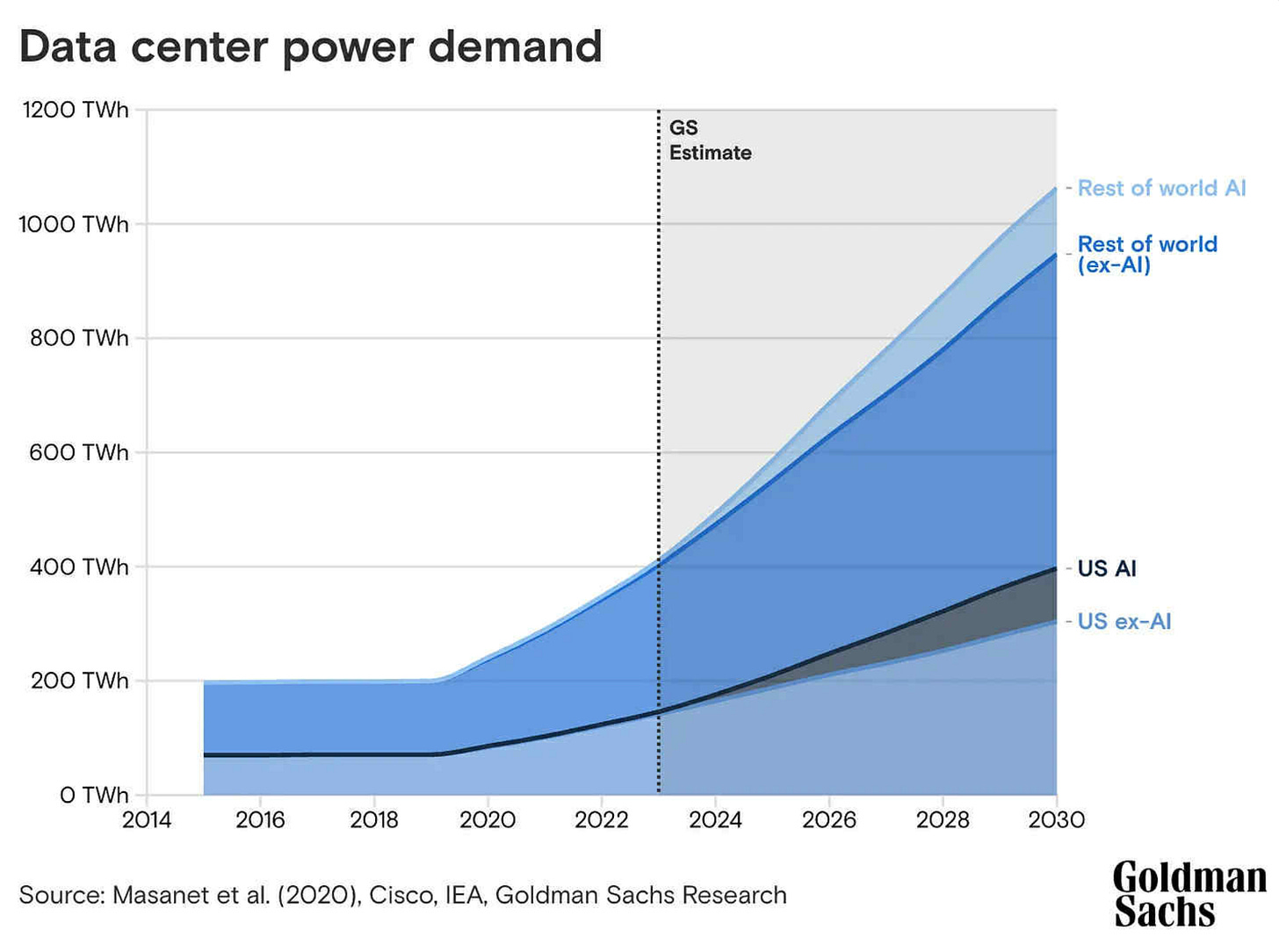

Simply showing the number of data centers doesn’t show the impact of AI specifically, or how much power data centers are drawing. Power roughly correlates with water, because the more energy is used in data center computers, the more they need to be cooled, and the more water is needed to do that. Here’s a graph showing the power demand of all data centers, and how much of that demand AI makes up.

Obviously there’s been a big uptick on power draw since 2019, but AI is still a small fraction of total data center power draw. I think Goldman Sachs underestimated AI’s power draw here, experts think it’s more like ~15% of total power used in data centers, but it’s important to understand that the vast majority of that original scary red data center graph isn’t AI specifically.

AI is going to be large part of the very large data center buildout that’s currently underway, but it’s important to understand that up until this point most of those data centers on the graph were just the buildout of the internet.

One more note, circling back again to Maricopa County.

The county is a gigantic city built in the middle of a desert. For as long as it’s existed, it’s been under high water stress. Everyone living there is aware of this. The entire region is (I say this approvingly) a monument to man’s arrogance.

The only reason anyone can live in Phoenix in the first place is that we have done lots of ridiculous massive projects to move huge amounts of water to the area from elsewhere.

This is an area where environmentalism and equity come apart. I’d like residents of Phoenix to have access to reliable water supplies, but I don’t think this the most environmentalist move. I think the most environmentalist move would probably be to encourage people to leave the Phoenix area in the first place and live somewhere that doesn’t need to spend over two times as much energy as the country on average pumping water. I have to bite the bullet here and say that between environmentalism and equity, I’d rather choose equity and not raise people’s water prices much, even though they’ve chosen to live in the middle of a desert.

It seems inconsistent to think that it’s wrong for environmentalist reasons to build data centers near Phoenix that increase the city’s water use by 0.1%, but it’s not wrong for Phoenix to exist in the first place. If it’s bad for the environment to build data centers in the area at all, Phoenix’s low water bills themselves seem definitionally bad for the environment too. I think you can be on team “Keep Phoenix’s water bills low, and build data centers there” or team “Neither the data centers nor Phoenix should be built there, we need to raise residents’ water bills to reflect this fact” but those are the only options. I’m on team build the data centers and help out the residents of Phoenix.

More Perfect Union

More Perfect Union is one of the single largest sources of misleading ideas about data center water usage anywhere. They very regularly put out wildly misleading videos and headlines. There are so many that I’ve written a long separate post on them here. They are maybe the single most deceptive media organizations in the conversation relative to their reach.

Empire of AI

Karen Hao’s book Empire of AI was very popular and influenced the AI/environment conversation. It includes a chapter called “Plundering the Earth” that covers AI water and environmental issues. Unfortunately this section is one of the most misleading pieces of coverage of AI water issues that I’ve read. Within 20 pages, Hao manages to:

Claim that a data center is using 1000x as much water as a city of 88,000 people, where it’s actually using about 0.22x as much water as the city, and only 3% of the municipal water system the city relies on. She’s off by a factor of 4500.

Imply that AI data centers will consume 1.7 trillion gallons of drinkable water by 2027, while the study she’s pulling from says that only 3% of that will be drinkable water, and 90% will not be consumed, and instead returned to the source unaffected.

Paint a picture of AI data centers harming water access in America, where they don’t seem to have caused any harm at all.

Frame Uruguay as using an unacceptable amount of water on industry and farming, where it actually seems to use the same ratio as any other country.

Frame the Uruguay proposed data center as using a huge portion of the region’s water where it would actually use ~0.3% of the municipal water system, without providing any clear numbers.

These are all the significant mentions of data centers using water in the book.

There’s too much to say on this one for this section, so I made it its own post:

Empire of AI is wildly misleading about AI water use

·

Nov 16

Note: the author took the time to respond to me below. While I’m very grateful, the materials she sent actually seems to confirm my main criticism and I’m now very confident a key number in the book is 1000x too large and needs to be revised. I summarize everything in my reply here

4 common misleading ways of reporting AI water usage statistics

Comparing AI to households without clarifying how small a part of our individual water footprint our households are

Many articles choose to report AI’s water use this way:

“AI is now using as much as (large number) of homes.”

Take this quote from Newsweek:

In 2025, data centers across the state are projected to use 49 billion gallons of water, enough to supply millions of households, primarily for cooling massive banks of servers that power generative AI and cloud computing.

That sounds bad! The water to supply millions of homes sounds like a significant chunk of the total water used in America.

The vast majority (~93%) of our individual total consumption of freshwater resources does not happen in our homes, it happens in the production of the food we eat. Experts seem to disagree on exactly what percentage of our freshwater consumption happens in our homes, but it’s pretty small. Most estimates seem to land around 1%. So if you just look at the tiny tiny part of our water footprint that we use in our homes, data centers use a lot of those tiny amounts. But if you look at the average American’s total consumptive water footprint of ~1600 L/day, 49 billion gallons per year is about 300,000 people’s worth of water. That’s about 1% of the population of Texas. The entire data center industry (both for AI and the internet) using as much water as 1% of its population just doesn’t seem as shocking.

Referencing the “hidden, true water costs” that AI companies are not telling you, without sharing what those very easily accessible costs are

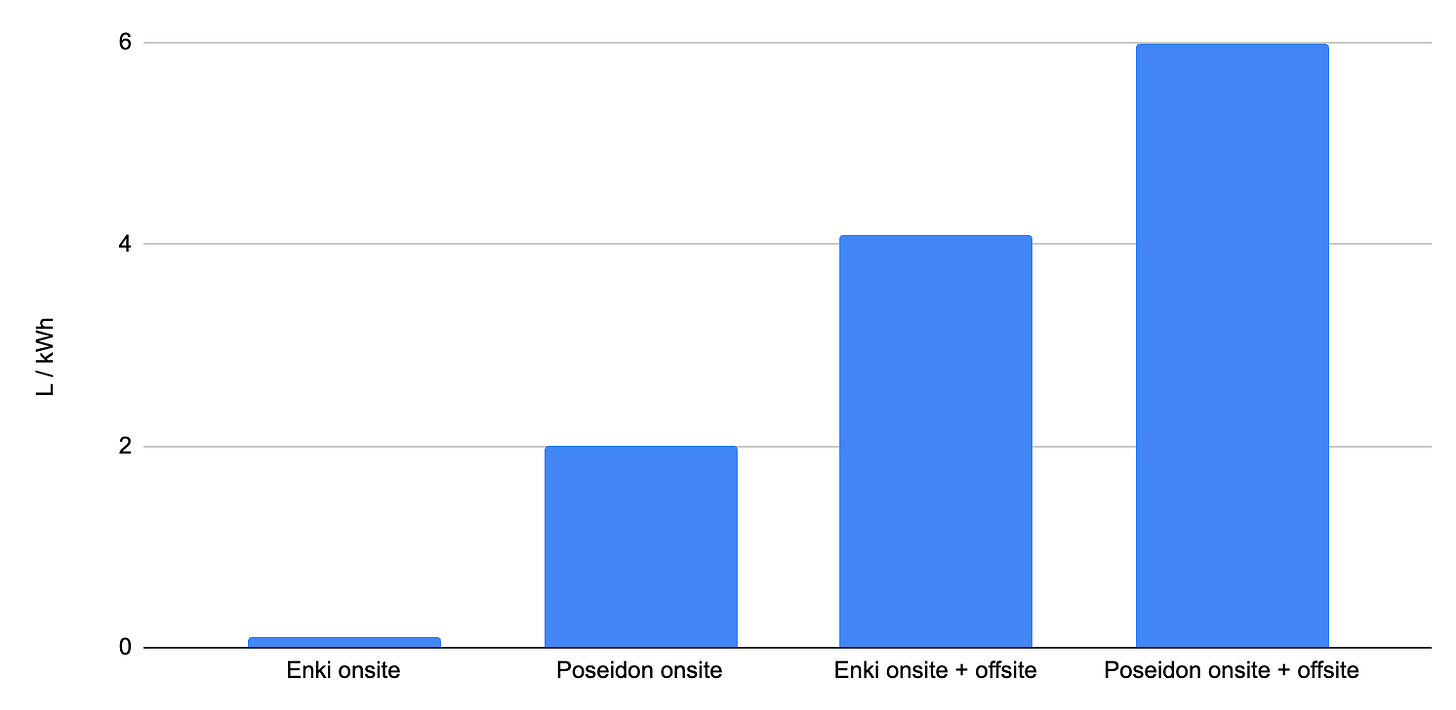

A move that I complained about in my last post is that a lot of articles will imply that AI companies are hiding the “true, real” water costs of data centers by only reporting the “onsite” water use (the water used by the data center) and not the “offsite” water use (the water used in nearby power plants to generate the electricity). Reporting both onsite and offsite water costs has become standard in reporting AI’s total water impact.

Many authors leave their readers hanging about what these “true costs” are. They’ll report a minuscule amount of water used in a data center, and it’s obvious to the reader that it’s too small to care about, but then the author will add “but the true cost is much higher” and leaves the reader hanging, to infer that the true cost might matter.

We actually have a pretty simple way of estimating what the additional water cost of offsite generation is. Data centers on average use 0.48 L of water to cool their systems for every kWh of energy they use, and the power plants that provide data centers energy average 4.52 L/kWh. So to get a rough estimate:

If you know the onsite water used in the data center, multiply it by 10.4 to get the onsite + offsite water.

If you know the onsite energy used, multiply it by 5.00 L/kWh to get the onsite + offsite water used.

Obviously scaling up a number by a factor of 10 is a lot, but it often still isn’t very much in absolute terms. Going from 5 drops for a prompt to 50 drops of water is a lot relatively, but in absolute terms it’s a change from 0.00004% of your daily water footprint to 0.0004%. Journalists should make these magnitudes clear instead of leaving their readers hanging.

This talking point can be doubly deceptive if you only look at the proportion

Let’s say there are 2 data centers in a town (I’ll call them Poseidon and Enki) drawing from the same power source. The local town’s electricity costs 4 L of water per kWh to generate.

The Poseidon data center is pretty wasteful with its cooling water. It spends 2 L of water on cooling for every kWh it uses on computing, way above the national average of 0.48L/kWh. So if you add the onsite and offsite water usage, Poseidon uses 6 L of water per kWh.

The Enki data center finds a trick to be way more efficient with its cooling water. It drops its water use down to 0.1L/kWh. Well below the national average. So if you add its onsite and offsite water usage, it uses 4.1 L per kWh without using any more energy.

Obviously, the Enki data center is much better for the local water supply.

Both data centers are asked by the town to release a report on how much water they’re using. They both choose to only report on the water they’re actually using in the data center itself.

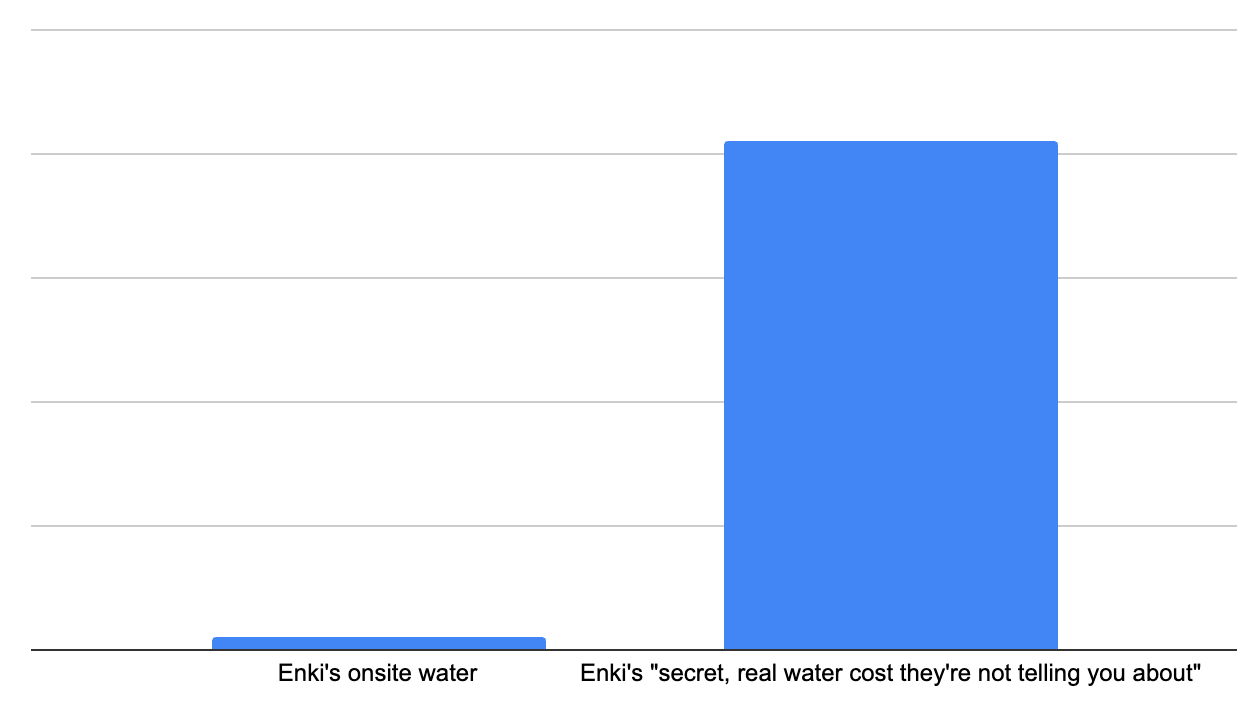

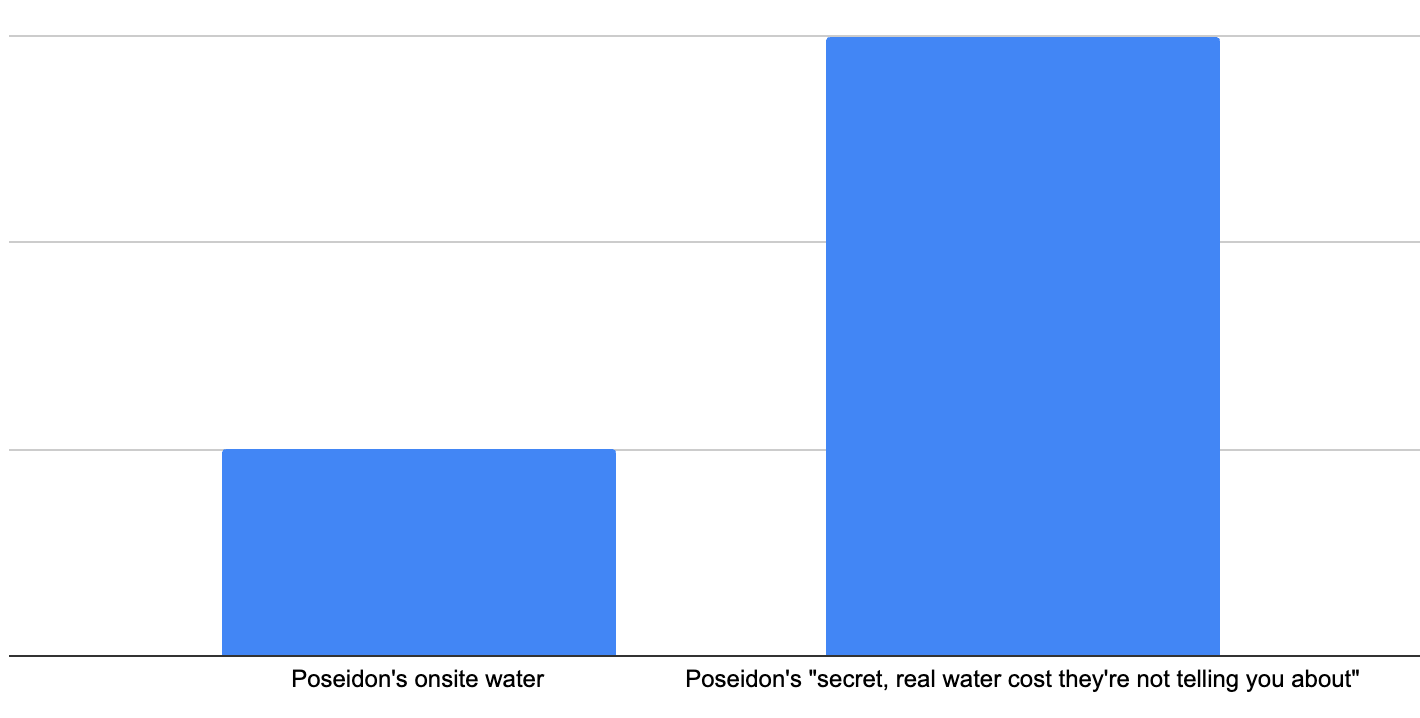

Suddenly, a local newspaper shares an expose: both data centers are secretly using more water than they reported, but Enki’s secret, real water use is 41x its reported water costs.

While Poseidon’s is only 3x its reported water costs:

Here, Enki looks much more dishonest than Poseidon. If readers only saw this proportion, they would probably be left thinking that Enki is much worse for the local water supply. But this is wrong! Enki’s much better. The reason the proportions are so different is that Enki’s managed to make its use of water so efficient compared to the nearby power plant.

I think something like this often happens with data center water reporting.

When I wrote about a case of Google’s “secret, real water cost” actually not being very much water, a lot of people messaged me to say Google still looks really dishonest here, because the secret cost is 10x its stated water costs once you add the offsite costs. A way of reframing this is to say that Google’s made its AI models so energy efficient that they’re now only using 1/10th as much water in their data centers per kWh as the water required to generate that energy. This seems good! We should frame this as Google solidly optimizing its water use.

Take this quote from a recent article titled “Tech companies rarely reveal exactly how much water their data centers use, research shows”:

Sustainability reports offer a valuable glimpse into data center water use. But because the reports are voluntary, different companies report different statistics in ways that make them hard to combine or compare. Importantly, these disclosures do not consistently include the indirect water consumption from their electricity use, which the Lawrence Berkeley Lab estimated was 12 times greater than the direct use for cooling in 2023. Our estimates highlighting specific water consumption reports are all related to cooling.

The article should have mentioned that this means data centers have made their water use so efficient that basically the only water they’re using at all is in the nearby power plant, not in the data centers themselves. But framing it in the original way way make it look like the AI labs are hiding a massive secret cost from local communities, which I guess is a more exciting story.

Vague gestures at data centers “straining local water systems” or “exacerbating drought” without clarifying what the actual harms are

If you use literally any water in any area with a drought, you’re in some sense “straining the local water system” and “exacerbating the drought.” Both of these tell us basically nothing meaningful about how bad a data center is for a local water system. If an article doesn’t come with any clarification at all about what the actual expected harms are, I would be extremely wary of this language. In basically every example I can find where it’s used, the data centers are adding minuscule amounts of water demand to the point that they’re probably not changing the behavior of any individuals or businesses in the area.

Simply listing very large numbers without any comparisons to similar industries and processes

This is the great singular sin of bad climate communication. The second you see it, you should assume it’s misleading. Simply reporting “millions of gallons of water” without context gives you no information. The power our digital clocks draw use millions of gallons of water, but digital clocks aren’t causing a water crisis. Whenever you see an article cite a huge amount of water with no comparisons at all to anything to give you a proper sense of proportion, ask a chatbot to contextualize the number for you.

The future

Obviously this could all change in the future. Data centers are growing rapidly. I don’t know how to forecast how much data centers will impact water use over the next few years. Experts have tried, but it’s all pretty murky. For now, it doesn’t seem like data centers are affecting households’ access to water.

Further reading

The Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory’s report on data center energy and water use in 2024 is the most comprehensive document we have on AI and water right now.

Brian Potter’s recent piece on water and update on data center water use.

Hannah Ritchie has some recent great stuff on data centers and chatbots

Matt Yglesias’s piece on data centers and water

Friend of the blog SE Gyges has a great breakdown of the single most popular statistic about ChatGPT that’s also a lie: it uses a bottle of water per email.

I think here we should treat AI like any other private industry. Private companies who want to use water need to buy it from the utility, and they might need to compete with each other if water is scarce by paying a little more for it. If data centers are competing with households for water, that seems bad, but if data centers are competing with golf courses for water use, I’d really rather the water go to the data center. Most places have separate water rates for residential vs. commercial/industrial water use, and they do this to keep the water markets somewhat separate so competition between firms doesn’t end up affecting household water. Data centers should be allowed to compete with other private businesses.

This is very hard to correctly estimate. I agree with Brain Potter’s reasoning here.

From this paper. It’s very very hard to find good stats on this and they seem to disagree with each other. I’m using this as the middle of the range I found. Most of this water use is used in agriculture to grow our food.

Page 7-9

Will type up how I got these soon.

I wish this were surprising to me, but AI news reporting has come up with so many outright bizarre "as much power as the Eiffel Tower in 17 years" and "all the factories in Nepal in a month" type analogies that I've become extremely cynical on this topic. Or training electricity expressed as some apparently staggering number of households... that turns out to be equal to less than 1% of annual global population growth, which is furthermore cumulative.

Working journalists by and large don't like generative AI, don't like big tech, and are overly trusting of sources critical of both. At the same time, they are highly inclined to be convinced by narratives, particularly those that cast them in the role of the hero. This doesn't require any malice, just a desire to tell the story that they feel must be told:

"As the dark side of AI was gradually exposed, and the stochastic parrots fell far short of their promise, the bubble burst and people gradually swore off AI. After calls from artists, writers, medical professionals and environmentalists that Something Must Be Done, [some thing] was done, and then everything went back to how it was and always will be, and the news cycle moved on."

Some of the more "big picture" articles in recent weeks seem to express bafflement that this just isn't playing out and people are still using ChatGPT. Go figure.

That was an interesting read, but for the 2nd assumption stating that total data center water usage is 67 million gallons a day, I was looking at the LBNL report Brian Potter cited for that 67 million gallons per day figure and you put in the further reading section, and 2 things come to mind. First, the water consumption data within the cited report is for 2023, not 2024.

Secondly, Potter's reduction of the 579 million gallons/day to the 19 million gallons/day attributed to indirect consumption (electricity generation) seems to assume that the first figure is the water withdrawal rate, not the water consumption rate, but the LBNL report explicitly defines water consumption as the following in the page before (56): "Water consumption refers to the amount of withdrawn water that is permanently removed from the immediate water cycle due to evaporation or other irreversible processes."

Looking at an alternate source for verification, from Meta's own sustainability report (https://sustainability.atmeta.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/08/Meta-2024-Sustainability-Report.pdf), for 2023 they report 14,975,435 MWh of electricity consumed by data centers, for 58,475 megaliters of water consumption from purchased electricity (99%+ of their electricity by source). That comes to 3.90 liters of water consumed per KWh, and Meta's own definition of water consumption is the difference between the water taken out from a source (withdrawal) and what is discharged back into the water. For reference, the LBNL report used an estimate of 4.52 liters of water consumed per KWh to get to their consumption figure.

The LBNL report states that total electricity usage for all datacenters was 176 TWh, so 176,000,000,000 KWh * 3.90 liters = 686,400,000,000 liters = 181,327,696,738.633 gallons / year. Dividing by 365 gets 496,788,210 gallons, or 496 million gallons of water per day. There are other water consumption figures I looked at ranging from around 2 gallons/7.5 litres per KWh to 0.52 gallons/2 liters per KWh, but even at the lowest figure, that's still more than 345 million gallons per day of water consumption, which exceeds the 19 million gallons per day indirect consumption figure by a significant margin.