Requests for journalists covering AI and the environment

Always aim to give your reader a full picture of the environmental issues a community and the world is facing

I’ve been in more conversations with journalists about AI and the environment recently and wanted to get some basic points down. These are my asks as someone who’s had a lot of specific issues with the way AI and the environment has been covered in the last few years. My main worry hasn’t been that AI’s being unfairly attacked. It’s more that readers are coming away with wildly inaccurate beliefs about where AI and data centers fit into the broader environmental picture. Getting this right matters a lot, because it’s very hard to keep people’s attention on climate and the environment for long. If they get distracted by a relatively small issue, they miss the opportunity to do a lot more good elsewhere. My ask isn’t that you present AI positively or negatively, it’s that you aim to give readers an accurate picture of its place in the environmental issue, and not leave them less informed about where the most pressing environmental problems are in their communities and the world more broadly.

These are all my requests. I go into more detail on each below:

Don’t imply that data centers make the computer processes inside less efficient.

For context, this recent critical story on data center buildouts checks my boxes for great coverage. I think more writing should aim for this level of quality.

The big ultimate goal: readers should leave your story with a better understanding of how data centers fit into the broader environmental problems a region or the world is facing.

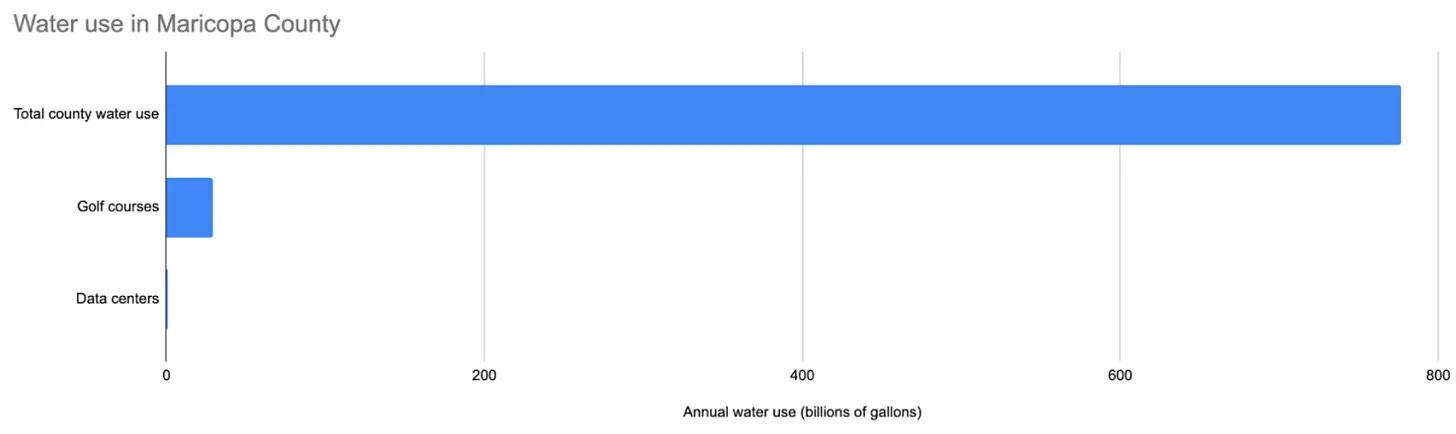

If a reader leaves your story convinced that data centers are the main unique threat to a region’s water, when golf courses in the region are using 30 times more, readers have been misinformed. This often happens in coverage of data centers in Maricopa County Arizona, where data centers are framed as a unique water catastrophe for the region, but are actually using 0.12% of the county’s water, whereas golf courses use 3.8%. If you write a story about Maricopa County or somewhere else, a reader shouldn’t later be shocked to see this graph:

This is a good general rule of thumb. If after reading your article, a reader can feel shocked and confused to see some simple data completely clash with the vibes of what they just read, the article has miscommunicated the problem.

Don’t ever share contextless large numbers.

This is the singular sin of bad writing on the environment. There are 8 billion people. Anything used by even a small fraction of people globally will use huge amounts of resources by the standards of one individual person, to the point that literally anything in society can overwhelm us with its scale. If you don’t give readers a sense of proportion, you’re leaving them in the dark and unable to make good decisions about the environment. Don’t merely write “10 million gallons of water per year” or “200,000 bottles of water per day” in a vacuum. This is a huge amount of water by the standards of any individual, but it’s also about 10% of the water a large car factory might use. If you drop a lot of huge contextless numbers on your readers, they will basically always be alarmed, whether there’s a “thousand” or “million” or “billion” involved. A reader leaving your article should not be surprised to later find out that the data center you described uses as a car factory.

My favorite book on good environmental communication (that I’d assign to everyone covering this if I could) is Sustainable Energy - Without the Hot Air by David MacKay. The book’s available for free online. This quote from the introduction captures how useless and harmful it is to share contextless large numbers:

This heated debate is fundamentally about numbers. How much energy could each source deliver, at what economic and social cost, and with what risks? But actual numbers are rarely mentioned. In public debates, people just say “Nuclear is a money pit” or “We have a huge amount of wave and wind.” The trouble with this sort of language is that it’s not sufficient to know that something is huge: we need to know how the one “huge” compares with another “huge,” namely our huge energy consumption. To make this comparison, we need numbers, not adjectives.

Where numbers are used, their meaning is often obfuscated by enormousness. Numbers are chosen to impress, to score points in arguments, rather than to inform. “Los Angeles residents drive 142 million miles – the distance from Earth to Mars – every single day.” “Each year, 27 million acres of tropical rainforest are destroyed.” “14 billion pounds of trash are dumped into the sea every year.” “British people throw away 2.6 billion slices of bread per year.” “The waste paper buried each year in the UK could fill 103448 double-decker buses.”

If all the ineffective ideas for solving the energy crisis were laid end to end, they would reach to the moon and back.... I digress.

The result of this lack of meaningful numbers and facts? We are inundated with a flood of crazy innumerate codswallop. The BBC doles out advice on how we can do our bit to save the planet – for example “switch off your mobile phone charger when it’s not in use;” if anyone objects that mobile phone chargers are not actually our number one form of energy consumption, the mantra “every little helps” is wheeled out. Every little helps? A more realistic mantra is:

if everyone does a little, we’ll achieve only a little.

Readers should leave understanding that the energy and water used by individual prompts doesn’t meaningfully add to their personal carbon or water footprints.

Simply reporting a ChatGPT prompt uses “ten times as much energy as a Google search” doesn’t give a reader much useful information. It’s fine to report on its own, but it shouldn’t be used to imply that ChatGPT is going to become a noticeable part of a person’s daily carbon footprint. Google searches use tiny amounts of energy. Wouldn’t it be weird to hear a climate scientist say you should limit your Google searches? It’s like saying that a digital clock uses 1 million times as much power as an analog watch. That’s true, but it’s such a minuscule amount of power that they both round to zero. Readers should be left understanding that their individual prompts are not really affecting their carbon or water footprints at all. The average American would have to prompt ChatGPT 1000 times per day to raise their carbon footprint by 1%. They would have to prompt it 8,000 times per day to raise their water footprint by 1%. But if they were doing this, they would likely be skipping other activities that were way more harmful to the environment. I’ve read too many articles that give readers the sense that using chatbots can somehow meaningfully contribute to their individual environmental footprint. Even if you try to include every last way chatbots affect the environment, the numbers just don’t add up. It is wildly misleading to imply that using AI raises your personal carbon or water footprint.

Compare data centers to other industries and commercial buildings, not household use of energy and water.

Because AI and the digital economy are large general industries in America, their proper context is other industries, not large multiples of personal lifestyle things individual people do. It would be weird for me to compare the American auto industry’s energy use to the energy I use in my home. Better comparisons would be to the steel industry, or agricultural industry, or other places where I can understand how car manufacturers fit into the big picture of America’s industrial use of energy and water. Simply reporting “Wow, the auto industry uses millions of times as much energy as Andy! Shocking.” would give readers no useful information.

But most media I’ve seen about AI data centers seems to only ever compare AI energy and water to massive multiples of personal household use, not to other normal industries. Take this recent example from the BBC:

The video announces that all data centers in Scotland are using 27 million bottles of tap water every year. That’s a weird way to talk about a large industry and doesn’t give the viewer any context for how data centers compare to other industries. If we make the comparison, we find that all data centers in Scotland combined are using just 4% of the water used by a single large car factory. That’s just 0.004% of Scotland’s total water use. This is a much more helpful comparison for readers. Many viewers would likely be confused if after watching this video, they discovered that everyone involved had been talking about a single car factory in Scotland. It gives viewers a wildly misleading impression of where water’s actually being used. Because most water use is in agriculture and industry, not in households, you should be sure to give readers context for how much resources data centers are using by comparing them to factories, farms, and other things that use larger amounts of water.

This is a very easy move to make. It doesn’t add many words to your piece, and gives readers a much more complete picture of how data centers compare to other industries.

These are some specific ways data centers are often talked about that other industries aren’t:

Anything referencing “community water” as in “data centers want to tap into local community water.” Most water in America is used for large scale agriculture and industry, not households. Any industry could be said to be “tapping into community water.” It would be strange to read an article about the Detroit auto industry “tapping into Detroit’s community water” even though the auto industry there uses millions of gallons of water per day. It’s understood that most parts of the country have both industry, commercial buildings, and homes, and in fact places are often benefited by having more industry and commerce.

Ominous stories of data centers “using more than 20% of a town’s water.” This only sounds shocking if you don’t think of data centers as any other industry. If a factory or large college were built in a small town, and you found out either were using 20% of the town’s water, this would make sense. The main business in the town would use a big chunk of its resources. This can often be beneficial, as it gives local utilities more money to invest back into improving service.

Criticize AI specifically, but don’t imply that it’s inherently weird or bad to spend physical resources on digital products.

The digital economy more broadly has been a gigantic civilizational achievement for transmitting valuable information. It’s part of what’s contributed to dematerialization where over time we’ve had more economic growth using less physical resources and energy. Digital goods are valuable because information is valuable. You can hate AI and think it’s all bad or useless, but don’t imply that it’s wasteful to spend physical resources on digital goods in general. Computers are the most efficient way to deliver information. Information is valuable. The value of a book is mostly in the information it contains, not the physical paper or ink that make it up. It’s okay and good to spend physical resources to acquire information, especially when doing it digitally is saving physical costs elsewhere.

Don’t imply that data centers make the computer processes inside less efficient.

Data centers are the most efficient ways to do large-scale computing. This point seems obvious, but I’ve met a lot of people who follow AI and the environment in their spare time who seem to think that the environment would be helped if we didn’t use data centers and ran more computer processes in our homes. This would actually be pretty terrible, everything we did would use way more energy. I’m not sure where they’re getting this idea, but the ways data centers are framed sometimes seems to contribute.

Don’t imply that data centers are new or uncommon.

Massive AI data centers are new, but readers should also understand that everything they do online besides AI has always used energy and water in data centers. I meet a lot of people who talk as if AI is the only digital product we use that uses water. There are ~5,400 data centers in the country. 99% of Americans live within 50 miles of a data center. They are ubiquitous and normal. Make sure to distinguish massive new AI data centers from all the others.

Don’t leave readers to infer for themselves that data centers have caused specific catastrophes that haven’t actually happened.

A very common move in a lot of reporting on data centers and water is to say that data centers “can create problems for community access to water” or “data centers can drain local aquifers” without once mentioning that of all 5,400 data centers in the US, none of them have done either. It’s true that they technically “can” create problems for access to water, because they use water! This is true of any industry. Anything that’s clearly meant to let a reader infer something has happened that hasn’t confuses them and leaves them less informed.

Water-specific asks

Don’t report a data center’s water permit as the amount of water it will actually regularly use.

Many (I’d say the majority) of articles I’ve read on data center water use frame the data center’s water permit as the amount of water it will actually use. This is wildly misleading. Water permits are difficult to amend, so data centers request the absolute most water they would need in extreme situations to give themselves a safe upper bound.

Don’t frame the offsite water use as “hidden” that the companies are dishonestly keeping secret.

The companies that run data centers often don’t have access to exactly how much water the power plants they draw from on the grid use. If a data center reports “We will use x amount of water” to the public, it seems reasonable for the public to assume that they are only talking about the water used in the building. If data centers become more efficient, that means that they use less water relative to the power plants around them. But this also means that the “hidden” cost in the power plants is a much larger multiple of the data center’s water. Talking this way effectively punishes the most water-efficient data centers, and implies they’re actually worse because they have a much larger proportion of “hidden” water offsite. This is backwards. I explain this more here.

Don’t use “straining local water systems” or “exacerbating drought” as synonyms for “using any water at all in a high water stress area” without clarifying what the actual harms are.

Literally everything that uses water in a drought-prone area is “exacerbating the drought” and “straining the local water system.” But using those terms can give readers an inaccurate picture if they’re using an extremely small amount of the water. There are many articles referencing data centers “exacerbating drought” in Phoenix that don’t mention they’re only using 0.1% of the water there. Find more specific ways to get across how much they’re adding or not adding to the problem.

Just a thank you to Andy for responding to my question - I am delighted that you took the time! Regards, Michael

Hi, Andy. As always, I love your reasoning and share it with those who promulgate misconceptions about the relative impact of AI versus other technologies on the environment, especially since I'm quite focused on the environment and climate change as a key policy area. My question is about your disclosures. Do you not have an AI company leader on your Board of Directors at Effective Altruism? That doesn't disqualify you, of course, from having great information and perspectives, but it does raise the bar on your citation of sources and disclosing if you have any conflicts of interest. Thank you.