Using ChatGPT is not bad for the environment

And a plea to think seriously about climate change without getting distracted

I have a cheat sheet for this post summarizing the main points here. I’d actually recommend starting with that one!

I have a post here on responses to critiques of these posts. Since publishing this post, newer estimates have come out that seem to show ChatGPT uses about 1/10th of the energy I assumed in this post. I can write an update later, but for now assume that it’s 10x as efficient as what I’ve written here.

Contents

Intro

This post is about why it’s not bad for the environment if you or any number of people use ChatGPT, Claude, or other large language models (LLMs). You can use ChatGPT as much as you like without worrying that you’re doing any harm to the planet. Worrying about your personal use of ChatGPT is wasted time that you could spend on the serious problems of climate change instead.

This post is not about the broader climate impacts of AI beyond chatbots, or about whether LLMs are unethical for other reasons (copyright, hallucinations, risks from advanced AI, etc.). AI image generators use about the same energy as AI chatbots, so everything I say here about ChatGPT also applies to AI images. AI video generation specifically does seem to use a lot more energy, to the point that I wouldn’t use it for the environment. I explain that more here.

My goal is to fairly and charitably address each common environmental criticism of ChatGPT that’s normally brought up. If you think I’m getting anything wrong I’d really appreciate you saying so, either in the comments or somewhere else I can read it!

Why write this?

I don’t normally write simple debunking posts, but I talk and read about the debate around emissions caused by ChatGPT a lot and it’s completely clear to me that one side is getting it entirely wrong and spreading misleading ideas. These ideas have become so widespread that I run into them constantly, but I haven’t found a good summary explaining why they’re wrong, so I’m putting one together.

At the last few parties I’ve been to I’ve offhandedly mentioned that I use ChatGPT, and at each one someone I don’t know has said something like “Ew… you use ChatGPT? Don’t you know how terrible that is for the planet? And it just produces slop.” I’ve also seen a lot of popular Twitter posts confidently announcing that it’s bad to use AI because it’s burning the planet. Common points made in these conversations and posts are:

Each ChatGPT search emits 10 times as much as a Google search.

A ChatGPT search uses 500 mL of water.

ChatGPT as a whole emits as much as 20,000 US households per day.

Training an AI model emits as much as 200 plane flights from New York to San Francisco.

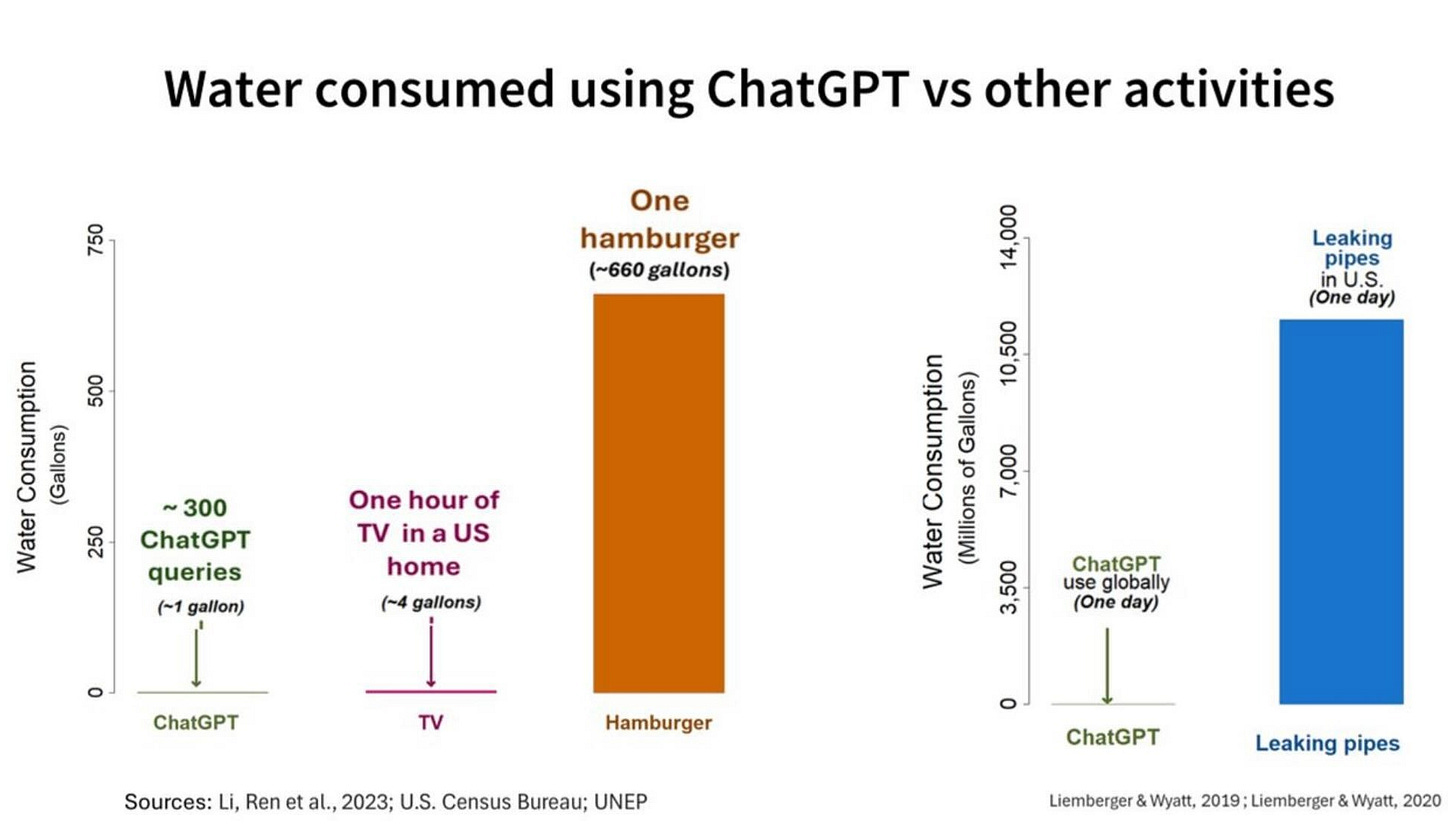

The one incorrect claim in this list is the 500 mL of water point. It’s a misunderstanding of an original report which said that 500 mL of water are used for every 20-50 ChatGPT prompts, not every prompt. Even that number is I think misleading (explained here) and the amount of water actually flowing in data centers is more like 500 mL of water per 300 searches. Every other claim in this list is true, but also paints a drastically inaccurate picture of the emissions produced by ChatGPT and other LLMs and how they compare to emissions from other everyday online activities. These are not minor errors. They fundamentally misunderstand energy use, and they risk distracting people who care about climate change.

One of the most important shifts in talking about climate has been the collective realization that individual actions like recycling pale in comparison to the urgent need to transition the energy sector to clean energy. The current AI debate feels like we’ve forgotten that lesson. After years of progress in addressing systemic issues over personal lifestyle changes, it’s as if everyone suddenly started obsessing over whether the digital clocks in our bedrooms use too much energy and began condemning them as a major problem.

Separately, LLMs have been an unbelievable life improvement for me. I’ve found that most people who haven’t actually played around with them much don’t know how powerful they’ve become or how useful they can be in your everyday life. They’re the first piece of new technology in a long time that I’ve become insistent that absolutely everyone try. If you’re not using them because you’re concerned about the environmental impact, I think that you’ve been misled into missing out on one of the most useful (and scientifically interesting) new technologies in my lifetime. If people in the climate movement stop using them they will miss out on a lot of value and ability to learn quickly. This would be a shame!

On a meta level, there’s a background assumption about how one is supposed to think about climate change that I’ve become exhausted by, and that the AI emissions conversation is awash in. The bad assumption is:

To think and behave well about the climate you need to identify a few bad individual actors/institutions and mostly hate them and not use their products. Do not worry about numbers or complex trade-offs or other aspects of your own lifestyle too much. Identify the bad guys and act accordingly.

Climate change is too complex, important, and interesting as a problem to operate using this rule. When people complain to me about AI emissions I usually interpret them as saying “I’m a good person who has done my part and identified a bad guy. If you don’t hate the bad guy too, you’re suspicious.” This is a mind-killing way of thinking. I’m using this post partly to demonstrate how I’d prefer to think about climate instead: we coldly look at the numbers, institutions, and actors that we can actually collectively influence, and we respond based on where we will actually have the most positive effect on the future, not based on who we happen to be giving status to in the process. I’m not inclined to give status to AI companies. A lot of my job is making people worry more about AI in other areas. What I want is for people to actually react to the realities of climate change. My claim in this post is that if you’re worried at all about your own use of AI contributing to climate change, you have been tricked into constructing monsters in your head and you need to snap out of it.

How should we think about the ethics of emissions?

Here are some assumptions that will guide the rest of this post:

You are trying to reduce your individual emissions

If you’re not trying to reduce your emissions, you’re not worried about the climate impact of individual LLM use anyway. I’ll assume that you are interested in reducing your emissions and will write about whether LLMs are acceptable to use.

There’s a case to be made that people who care about climate change should spend much less time worrying about how to reduce their individual emissions and much more time thinking about how to bring about systematic change to make our energy systems better (the effects you as an individual can have on our energy system often completely dwarf the effects you can have via your individual consumption choices) but this is a topic for another post.

The optimal amount of CO2 you emit is not zero

Our energy system is so reliant on fossil fuels that individuals cannot eliminate all their personal emissions. Immediately stopping all global CO2 emissions would cause billions of deaths. We need to phase out emissions gradually by transitioning to clean energy and making trade-offs in energy use. If everyone concerned about climate change adopted a zero-emissions lifestyle today, many of them would die. The rest would lose access to most of modern society, leaving them powerless to influence energy systems. Climate deniers would take over society. Individual zero-emissions living isn’t feasible right now.

In deciding what to cut, we need to factor in both how much an activity is emitting and how useful and beneficial the activity is to our lives. We should not cut an activity based solely on its emissions.

The average children’s hospital emits more CO2 per day than the average cruise ship. If we followed the rule “Cut the highest emitters first” we’d prioritize cutting hospitals over cruise ships—which is clearly a bad idea. Reducing emissions requires weighing the value of something against its emissions, not blindly cutting based on CO2 output alone. We should ask questions like “Can we achieve the same outcome with lower emissions?” or “Is this activity necessary?” But the rule “Find the highest emitting thing in a group of activities and cut it” doesn’t work.

In this post, I’ll compare LLM use to other activities and resources of similar usefulness. If you believe LLMs are entirely useless, then we should stop using them—but I’m convinced they are useful. Part of this post will explain why.

It is extremely bad to distract the climate movement with debates about inconsequential levels of emissions

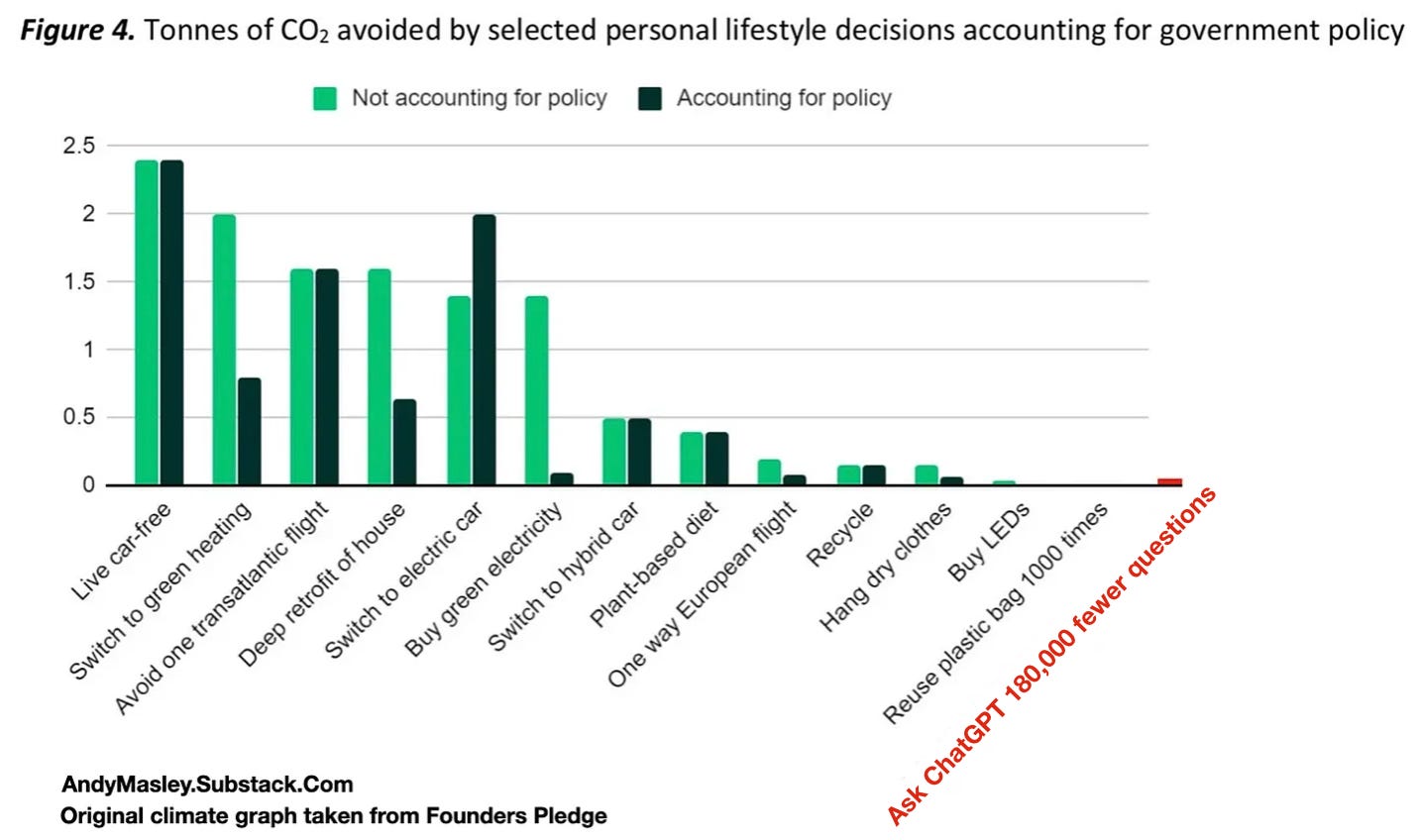

If climate change is an emergency that requires lots of people working collectively to fix in limited time, we cannot afford to get distracted by focusing too much of our effort and thinking on extremely small levels of emissions. The climate movement has seen a lot of progress and success in shifting its focus away from individual actions like turning off lights when leaving a room to big systematic changes like building smart grid infrastructure or funding clean energy tech. Even if you are only focused on lifestyle changes, it is best to focus on the most impactful lifestyle changes for climate. It would be much better for climate activists to spend all their time focused on helping people switch to green heating than encouraging people to hang dry their clothes. If the climate movement should not focus its efforts on getting individual people to hang dry their clothes, it should definitely not focus on convincing people not to use ChatGPT:

There are other environmental problems besides emissions

Another common concern about LLMs is their water use. This matters even though it’s not a direct cause of climate change. I’ll address that in the second part of the post. There might be other concerns as well (the su

pply chains involved in constructing data centers in the first place) but from what I can tell other environmental concerns also apply to basically all computers and phones, and I don’t see many people saying that we need to immediately stop using our computers and phones for the sake of the climate. If you think there are other bad environmental results of LLMs that I’m missing in this post, I’d be excited to hear about them in the comments!

It’s impossible to get very precise measurements of exactly how much energy individuals using extremely large complex systems are consuming

Any statistics about the energy consumption of individual internet activities have large error bars, because the internet is so gigantic and the energy use is spread across so many devices. Any source I’ve used has arrived at these numbers by dividing one very large uncertain number by another. I’ve tried my best to report numbers as they exist in public data, but you should assume there are significant error bars in either direction. What matters are the proportions more than the very specific numbers. If you think any of the statistics I’m using here are wrong, I’d really appreciate it if you let me know in the comments. I’m excited to update this post with the most reliable numbers I can get.

Are LLMs useful?

If LLMs are not useful at all, any emissions no matter how minute are not worth the trade-off, so we should stop using them. This post depends on LLMs being at least a little useful, so I’m going to make the case here.

I think my best argument for why LLMs are useful is to just have you play around with Claude or ChatGPT and try asking it difficult factual questions you’ve been trying to get answers to. Experiment with the prompts you give it and see if asking very specific questions with requests about how you’d like the answer to be framed (bullet-points, textbook-like paragraph) gets you what you want. Try uploading a complicated text that you’re trying to understand and use the prompt “Can you summarize this and define any terms that would be unfamiliar to a novice in the field?” Try asking it for help with a complicated technical problem you’re dealing with at work.

If you’d like testimonials from other people you can read people’s accounts of how they use LLMs. Here’s a good one. Here’s another. This article is a great introduction to just how much current LLMs can do.

LLMs are not perfect. If they were, the world would be very strange. Human-level intelligence existing on computers would lead to some strange things happening. Google isn’t perfect either, and yet most people get a lot of value out of using it. Receiving bad or incorrect responses from an LLM is to be expected. The technology is attempting to recreate a high level conversation with an expert in any and every domain of human knowledge. We should expect it to occasionally fail.

I personally find LLMs much more useful as a tool for learning than most of what exists on the internet outside of high quality specific articles. Most content on the internet isn’t the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, or Wikipedia. If I want to understand a new topic, it’s often much more useful for me to read a ChatGPT summary than watch an hour of some of the best YouTube content about it. I can ask very specific clarifying questions about a topic that it would take a long time to dig around the internet to find answers to.

I have a separate post here on the ways I use LLMs in my everyday life.

Main Argument

Emissions

What’s the right way to think about LLM emissions? Something suspicious a lot of claims about LLMs do is compare them to physical real-world objects and their emissions. When talking about global use of ChatGPT, there are a lot of comparisons to cars, planes, and households. Another suspicious move is to compare them to regular online activities that don’t normally come up in conversations about the climate (when was the last time you heard a climate scientist bring up Google searches as a significant cause of CO2 emissions?) The reason this is suspicious is that most people are lacking three key intuitions:

Without these intuitions, it is easy to make any statistic about AI seem like a ridiculous catastrophe. Let’s explore each one.

The incredibly small scales involved in individual LLM use

“A ChatGPT question uses 10 times as much energy as a Google search”

How much energy is this? A good first question to ask is when the last time was that you heard a climate scientist bring up Google search as a significant source of emissions. If someone told you that they had done 1000 Google searches in a day, would your first thought be that the climate impact must be terrible? Probably not.

The agreed-on best guess right now for the average chatbot prompt’s energy cost is actually the same as a Google search in 2009: 0.3 Wh. This includes the cost of the answering your prompt, idling AI chips between propmts, cooling in the data center, and other energy costs in the data center. This does not include the cost of training the model, the embodied carbon costs of the AI chips, or the fact that data centers typically draw from slightly more carbon intense sources. If you include all of those, the full carbon emissions of an AI prompt rise to 0.28 g of CO2. This is the same emissions as we cause when we use ~0.8 Wh of energy.

How concerned should you be about spending 0.8 Wh? 0.8 Wh is enough to:

Drive a sedan at a consistent speed for 4 feet

Spend 1 minute reading this blog post. If you’re reading this on a laptop and spend 20 minutes reading the full post, you will have used as much energy as 20 ChatGPT prompts. ChatGPT could write this blog post using less energy than you use to read it!

In Washington DC where I live, the household cost of 0.8 Wh is $0.00013. The average DC household uses 1,200,000 times as much energy every month.

If you’ve ever taken a trans-Atlantic flight, to match the energy you as a single passenger used on that one flight, you would need to ask ChatGPT 11,800,000 questions. That’s 400 questions every single day for 80 years, or one question for every 2 minutes that you’re awake for your entire life.

I probably ask ChatGPT and Claude around 8 questions a day on average. Over the course of a year of using them, this uses up the same energy as running a single space heater in my room for 30 minutes in total. Not 30 minutes per day, just a one-off use of a single space heater for 30 minutes.

Simply reporting one extremely small amount of energy as a multiple of another can lead to bad misunderstandings of how serious a problem is, because it’s easy for one extremely small quantity to be hundreds or thousands of times as large as the other and still not be large enough to concern us. A digital clock uses literally one million times as much power as an analog watch. I could write a long article about how replacing your watch with a digital clock is a million times as energy intensive as a way of telling time, and that we can’t afford such a drastic increase because we’re already in a climate emergency, but this would basically be a lie and would cause you to spend time worrying about something that doesn’t actually matter for the climate at all. I see the comparisons between ChatGPT and Google searches as basically equivalent to this.

Sitting down to watch 1 hour of Netflix has the same impact on the climate as asking ChatGPT 100 questions. I suspect that if I announced at a party that I had asked ChatGPT 100 questions in 1 hour I might get accused of hating the Earth, but if I announced that I had watched an hour of Netflix or that I drove 0.2 miles in my sedan the reaction would be a little different. It would be strange if we were having a big national conversation about limiting YouTube watching or never buying books or avoiding uploading more than 9 photos to social media at once for the sake of the climate. If this were happening, climate scientists would correctly say that the public is getting bogged down in minutia and not focusing on the big real ways we need to act on climate. Worrying about whether you should use LLMs is as much of a distraction to the real issues involved with climate change as worrying about whether you should stop the YouTube video you’re watching 4 seconds early for the sake of the Earth.

A ChatGPT subscription costs $20/month. It would be weird if OpenAI were using a lot more energy for each user than it could afford. As a baseline we should assume that ChatGPT uses about the same energy as other internet services we pay $20/month for. If it used a lot more, OpenAI would have to raise the price.

In my experience using ChatGPT is much more useful than a Google search to the point that I’d rather use it than search Google ten times anyway. I can often find things I’m looking for much faster with a single ChatGPT search than multiple Google searches. Here’s a search I did asking it to summarize what we know about the current and future energy sources used for American data centers. It also saves me a lot of valuable time compared to searching Google ten times.

How many people are actually using LLMs

A lot of complaints about the total energy used by LLMs (“ChatGPT uses more energy than 20,000 households” etc.) do not make sense when you consider the number of people using the LLMs. In considering LLM use, we can’t just look at their total emissions. We need to consider how many people are using them. If someone wanted to justify buying a private jet, they could correctly point out that Google as a company produces way more emissions than a single jet, so buying the jet is no big deal. This is silly because Google has billions of users and the jet has one, and Google is very efficient in terms of the energy consumed per user. Just saying how much energy ChatGPT as a whole is using without dividing by the number of users is similar to comparing Google to the jet. What matters is the energy per user, not just the total energy.

Here are some examples to illustrate the point:

“ChatGPT uses the same energy as 20,000 American households.”

ChatGPT as of the time of writing has 300,000,000 daily users and 1,000,000,000 daily messages answered. It’s the most downloaded app in the world. Let’s imagine that you can snap your fingers and create one additional American household, with all its energy demands and environmental impact. This American household is special. The people in the household have one hobby: spending all their time writing very detailed responses to emails. They enjoy doing this and never stop, and they’re so good at it that they have 15,000 people emailing them every day, each person sending on average 3.3 emails for a total of 50,000 emails per day, or 1 email every 2 seconds 24 hours per day. People seem to find their replies useful, because the rate of use just keeps going up over time. Would you choose to snap your fingers and create this household, even though it will have the climate impacts of one additional normal American household? Seems like a clearly good trade-off. What if you had the option to do that a second time, so now 50,000 more messages could be answered by a second household every day? Again, this seems worth the emissions. If you keep snapping your fingers until you meet the demand for their message replies, you would have created 20,000 new American households and have 1 billion messages answered per day. 20,000 American households is about the size of the Massachusetts city of Barnstable:

If one additional version of Barnstable Massachusetts appeared in America, how much would that make you worry about the climate? This would be an increase in America’s population of 0.015%. What if you found out that everyone who lived in the new town spent every waking moment sending paragraphs of extremely useful specific text about any and all human knowledge to the world and kept getting demands for more? Of all the places and institutions in America we should cut to save emissions, should we start by preventing that town from growing?

I think the conversation about energy use and ChatGPT sometimes leaves out that it’s the most downloaded app in the world. A headline that said “The most downloaded app on planet Earth is now using as much energy as the town of Barnstable” doesn’t seem shocking at all.

“Training an AI model emits as much as 200 plane flights from New York to San Francisco”

This number only really applies to our largest AI models, like GPT-4. GPT-4’s energy use in training was equivalent to about 200 plane flights from New York to San Fransisco. Was this worth it?

To understand this debate, it’s really helpful to understand what it means to actually train an AI model. Writing that up would take too much time and isn’t the focus of this post, so I asked ChatGPT to describe the training process in detail. Here’s its explanation. What’s important to understand about training a model like GPT-4 is

It’s a one-time cost. Once you have the model trained, you can tweak it, but it’s good to go and be used. You don’t have to continuously train it after for anywhere near the same energy cost.

It’s incredibly technologically complex. Training GPT-4 required 2 × 10²⁵ floating point operations (simple calculations like multiplication, subtraction, multiplication, and division). This is 70 million times as many calculations as there are grains of sand on the Earth. OpenAI had to wire together 25,000 state-of-the-art GPUs specially designed for AI together to perform these calculations over a period of 100 days. We should expect that this process is somewhat energy intensive.

It gave us a model that can give extremely long, detailed, consistent responses to very specific questions about basically all human knowledge. This is not nothing.

It’s rarely this large and energy intensive. There are only a few AI models as large as GPT-4. A lot of the AI applications you see are using the results of training GPT-4 rather than training their own models.

It's helpful to think about whether getting rid of "200 flights from New York to San Francisco" would really move the needle on climate. There are about 630 flights between New York and San Francisco every week. If OpenAI didn't train GPT-4, that would be about the same as there being no flights between New York to San Francisco for about 2 days. That's not 2 days per week. It's 2 days total. Even if ChatGPT had to be retrained every year (and remember, it doesn't) that is less than 1% of the emissions from flights between these two specific American cities. How much of our collective effort is it worth to stop this?

200 planes can carry about 35,000 people. About 20 times that amount of people fly from around the country to Coachella each year. There aren’t 20 AI models of equal size to GPT-4, so for the same carbon cost we could either cease all progress in advanced AI for a decade or choose not to run Coachella for 1 year so people don’t fly to it. This does not seem worth it.

To put a more specific number on the energy it took to train GPT-4, it’s about 50 GWh. GPT-4 was trained to answer questions, so to consider the energy cost we need to consider how many searches we have gotten out of that training energy use. I see the training cost as equivalent to comparing the cost of a shirt with how often you’ll wear it. If a shirt costs $40 and is well-made so that it will survive 60 washes, and another shirt is $20 but is poorly made so it will only survive 10 washes, then even though the first shirt is initially more expensive, it actually costs $0.67 per wear, while the second shirt costs $2 per wear, so in some meaningful way the first shirt is actually cheaper if you consider how you will actually use it, rather than just looking at the initial investment. In the same way, GPT-4’s training can look expensive in terms of energy if you don’t factor in just how many users and searches it will handle.

We don’t know exactly how many prompts GPT-4 handled. Experts agree that training AI is currently using ~40% of the energy costs of AI in data centers right now (the other 60% is when the models are used to answer questions) so we can assume for now that training each model is about 40% of its full lifetime emissions. This just means that we take the very small carbon cost per prompt, and roughly double it to get its full carbon costs, which I already did in the numbers above.

Other online activities’ emissions

When someone throws a statistic at you with a large number about a very popular product, you should be careful about how well you actually understand the magnitudes involved. We’re not really built for thinking about large numbers like this, so the best we can do is compare them to similar situations to give us more context. The internet is ridiculously large, complex, and used by almost everyone, so we should expect that it uses a large portion of our total energy. Anything widely used on the internet is going to come with eye-popping numbers about its energy use. If we just look at those numbers in a vacuum it is easy to make anything look like a climate emergency.

ChatGPT uses as much energy as 20,000 households, but Netflix reported using 450 GWh of energy last year which is equivalent to 40,000 households. Netflix’s estimate only includes its data center use, which is only 5% of the total energy cost of streaming, so Netflix’s actual energy use is closer to 800,000 households. This is just one streaming site. In total, video streaming accounted for 1.5% of all global electricity use, or 375,000 GWh, or the yearly energy use of 33,000,000 households. ChatGPT uses the same energy as Barnstable Massachusetts, while video streaming uses the same energy per year as all of New England, New York State, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania combined. Video streaming is using 1600x as much energy as ChatGPT, but we don’t hear about it as much because it’s a much more normal part of everyday life. 20,000 households can sound like a crazy number when you compare it to your individual life, but it’s incredibly small by the standards of internet energy use.

Here’s how many American households worth of energy different online activities use globally, all back of the envelope calculations I did with available info, plus an equivalent American city using the same energy. I factored in both the energy used in data centers and the energy used on each individual device. There are large error bars but the rough proportions are correct.

11,000 households - Barre, VT - Google Maps

20,000 households - Barnstable MA - ChatGPT

23,000 households - Bozeman, MT - Fortnite

150,000 households - Cleveland, OH - Zoom

200,000 households - Worcester, MA - Spotify

800,000 households - Houston, TX - Netflix

1,000,000 households - Chicago, IL - YouTube

Does this mean that we should stop using Spotify or video streaming? No. Remember the rule that we shouldn’t just default to cutting the biggest emitters without considering both the value of the product and how many people are using it. Each individual Spotify stream uses a tiny amount of energy. The reason it’s such a big part of our energy budget is that a lot of people use Spotify! What matters when considering what to reduce is the energy used compared to the amount of value produced, and other options to get the same service. The energy involved in streaming a Spotify song is much much less than the energy required to physically produce and distribute music CDs, cassettes, and records. Replacing energy-intensive physical processes with digital options is part of the reason the CO2 emissions per American citizen have dropped by over a quarter since their peak in the 1970s:

If people are going to listen to music, we should prefer that they do it via streaming rather than buying physical objects. Just saying that Spotify is using the same energy as a city without considering the number of users, the benefits they’re getting from the service, or how energy efficient other options for listening to music would be is extremely misleading. Pointing out that ChatGPT uses the same energy as 20,000 households without adding any other details is just as misleading.

Data centers have incredibly concentrated energy demands, but don’t add much overall to our national energy usage

If all this is true, why are there so many stories about AI data centers stressing local energy grids? There are stories of coal plants reopening to meet the data center energy demands.

The central environmental paradox of data centers

The environmental paradox of data centers is that they put so much strain on the surrounding energy grid because, not despite the fact that they have been made so uniquely energy efficient. This is due to the economies of scale that come with running so many servers in one building.

Data centers are very efficient

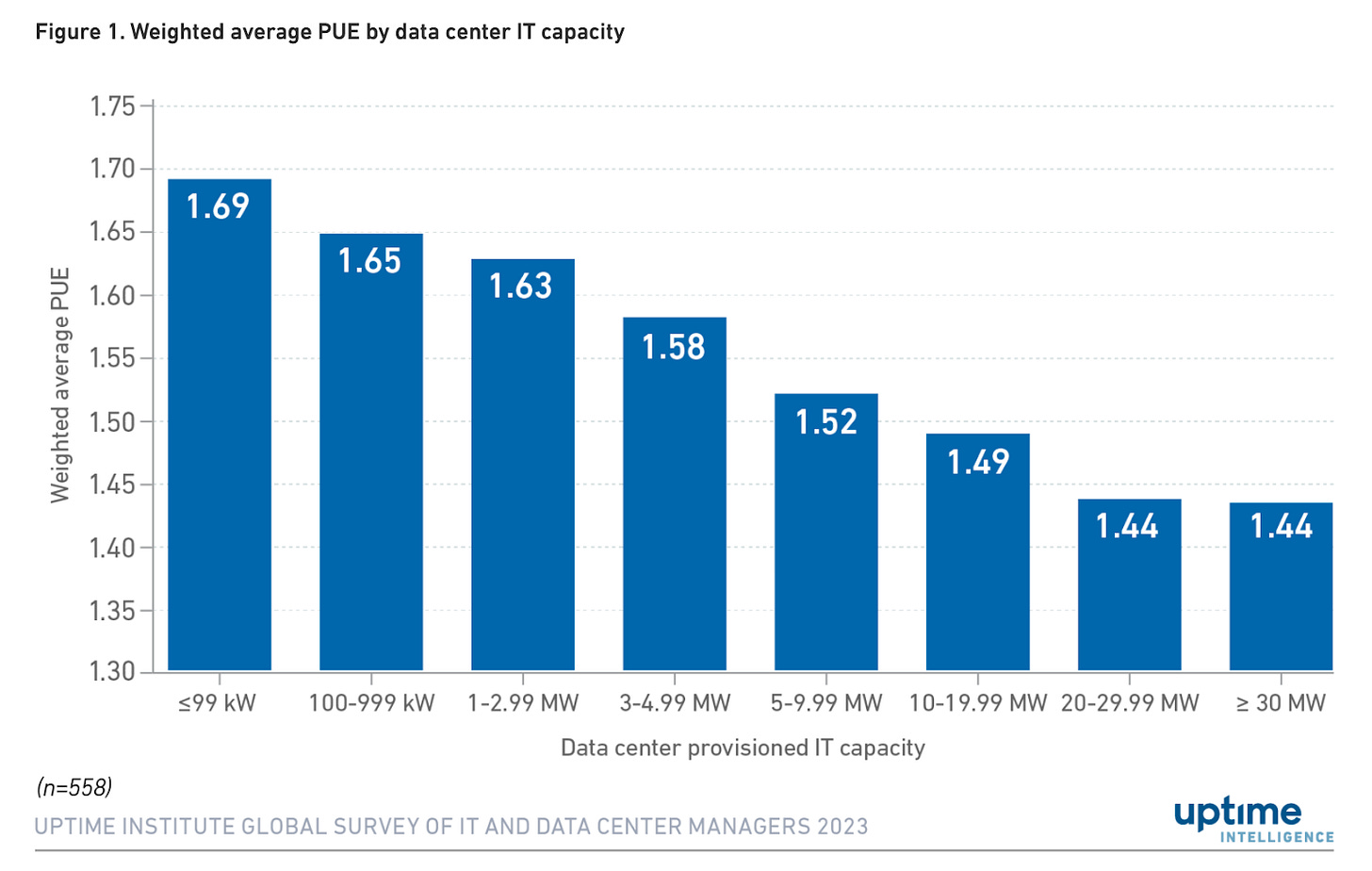

Power Usage Effectiveness (PUE) measures data center efficiency: total energy input divided by energy delivered to servers.

PUE = (Energy data center takes in/Energy data center delivers to servers)

A perfectly efficient data center would have a PUE of 1. The energy coming in would perfectly equal the energy used by the chips. No data center can actually achieve a PUE of 1, due to lighting, air conditioning, and heat loss.

PUE does not measure water use, or the carbon intensity of the electricity. Data centers use a separate WUE measure for water.

In practice, hyperscale data centers often achieve ~1.1. The industry average is ~1.56.

For context, power lines typically lose ~5% of energy during transmission, meaning they have an energy input-to-output ratio of 1.05. Google has achieved PUE below 1.05 at some of their data centers. This means Google has optimized their data center operations so efficiently that they waste less energy on non-computing infrastructure (cooling, lighting, etc.) than the average power line loses just moving electricity from point A to point B. In other words, their data centers are more energy-efficient at delivering power specifically to computing chips than the electrical grid is at simply transmitting power.

Many hyperscaler data centers are achieving very low PUEs because they are optimized at every level of design and operation. Because the companies using them are also running them, they have a financial incentive to optimize the data center’s energy use.

Larger data centers benefit from economies of scale: shorter transmission distances, reduced losses, and optimization opportunities unavailable to smaller facilities. There are other benefits to clustering AI chips together as well, but the energy benefits alone are significant. Larger data centers operate more efficiently.

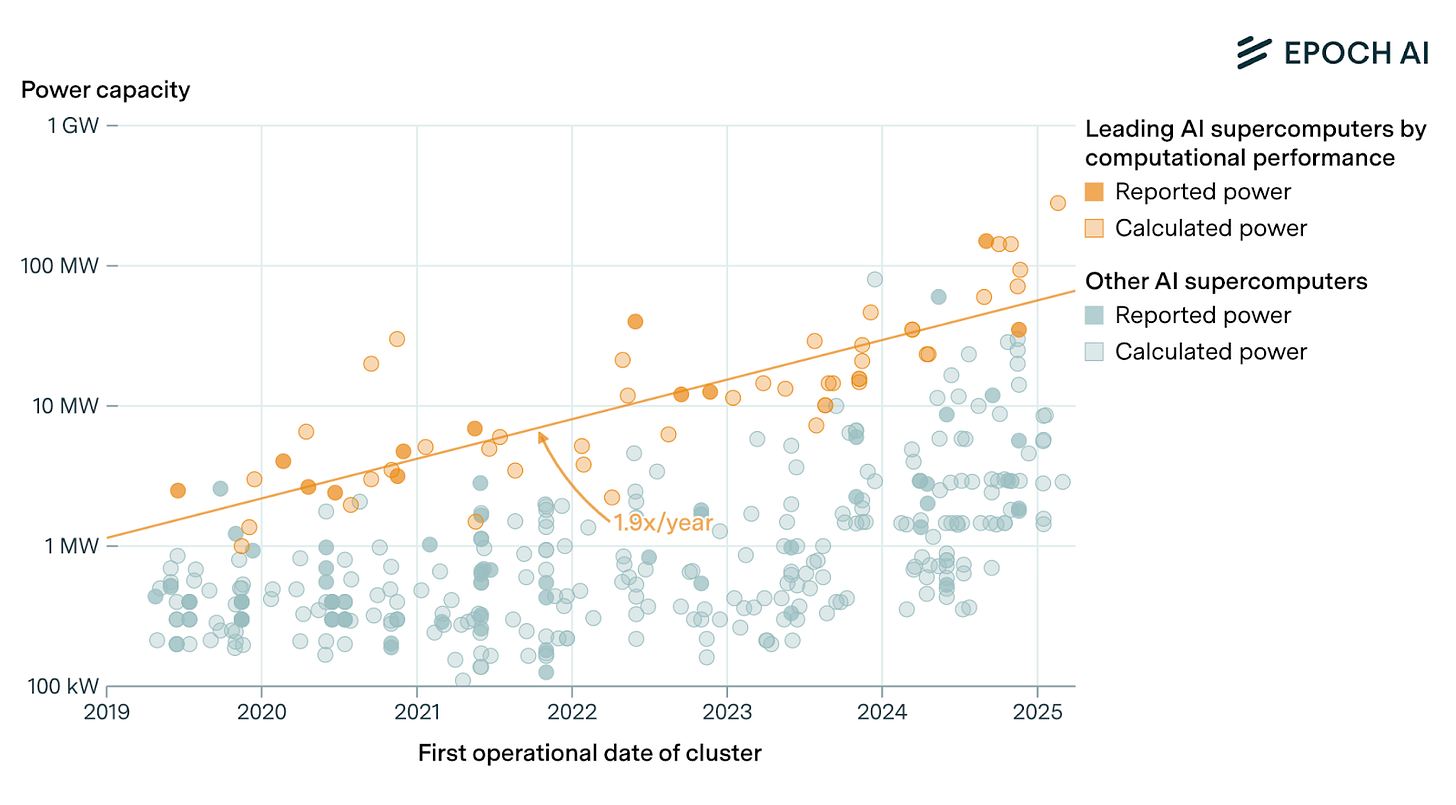

Data center power demand can get very large. For context, 30 MW of power (on the far right of the graph) is enough to power a town of about 60,000 people. xAI’s Colossus is the largest AI supercomputer, with a maximum power capacity of 280 MW, the same as a city with half a million people.

Because larger data centers are more energy efficient, if you want your AI prompt to use as little energy as possible, you should (all else equal) prefer it to be processed in a very large data center.

In general, data centers are the most energy-efficient way to do the large-scale computing that services like the internet and AI require. Companies already have financial incentive to make them efficient. If we hold the amount of computations equal, Data centers are the most energy-efficient method for large-scale computing.

Data center energy and water demands are high relative to most commercial buildings

Data centers have some of the most concentrated energy demands of any type of building. They also require constant reliable power. Their computers run 24/7, and because a single large data center is handling computing for so many people, even a brief power outage can be uniquely bad for the business. Data centers aspire to “five 9’s of reliability”: the center should function normally for 99.999% of the time. As a result, they strain local grid capacity.

This strain can lead to greater reliance on fossil fuels. This occurs through the concept of marginal emissions. When electricity demand rises, utilities must activate additional power sources. The "marginal" source (the next plant brought online) is often a fossil fuel "peaker plant" (a power plant called upon during times of high electricity demand to supply power to the grid, often using natural gas turbines that can start up quickly). These plants are designed to ramp up quickly but are often less efficient and more polluting per unit energy than the average grid mix.

A data center's constant, high demand reduces the grid's flexibility and increases the baseline load, making it more likely that these high-polluting marginal sources are used. Furthermore, the rapid growth of data center demand is outpacing the deployment of new renewable energy and transmission infrastructure. This has led utilities in several states, including Georgia, Kansas, and Virginia, to delay the retirement of older fossil fuel plants or propose new natural gas plants to ensure grid reliability.

So when a large new constant load like a data center is added, it can increase the amount of fossil generation needed at the margin, making the power they consume more carbon-intensive than the grid average. Data centers also maintain backup generators (often diesel) in case of outages.

The paradox

To recap:

Data centers are so uniquely energy efficient, and become more efficient the more computing they manage (due to economies of scale), that companies are incentivized to do gigantic amounts of computing in them, and keep them running 24/7. All else equal, if you want an AI tool to use the least energy possible, you should prefer it to be run in the biggest data center possible.

Because they concentrate so much computing inside, and need constant reliable power, even though each computation is energy efficient, overall data centers have the highest concentrations of energy demand of basically any commercial buildings.

Local energy and water grids were not designed with these hyper-concentrated, very constant demands in mind, so data centers can sometimes strain the capacity of local grids. This sometimes increases fossil fuel dependance, because they can provide more consistent backup power compared to renewables.

This demand puts a strain on the surrounding grid and sometimes favors the use of fossil fuels, even though (and actually because) what’s happening in the data center itself is so uniquely energy efficient.

The central paradox: data centers strain local grids precisely because they've been made so efficient.

Failing to understand this can lead to bad ideas for how to solve the growing problem of AI emissions. While it may be possible to make small improvements in data center efficiency, it’s unlikely that this would reduce emissions nearly as much as making the grid around data centers greener or enforcing stricter environmental regulations around how the data center generates back-up energy.

What should we expect to see based on the paradox of data centers?

Locally, we should expect data centers to have much higher rates of energy and water use than basically any other commercial or industrial buildings, and to put some strain on local grids as a result.

Globally, data centers should be a small part of energy and water use (and emissions), because they’re uniquely efficient with the resources they use.

The data confirms this. Individual data centers can grow so large that they take on the energy demands of whole cities, but globally all data centers on Earth (supporting the entire internet in addition to AI) use 1.5% of global electricity, and only 0.23% of global energy. Data centers are managing and hosting the global internet. The average person on Earth spends 6 hours and 40 minutes every day on the internet, so they’re spending 40% of their waking lives interacting with data centers. Data center efficiency means that something we all spend almost half our lives interacting with only uses 0.23% of our global energy.

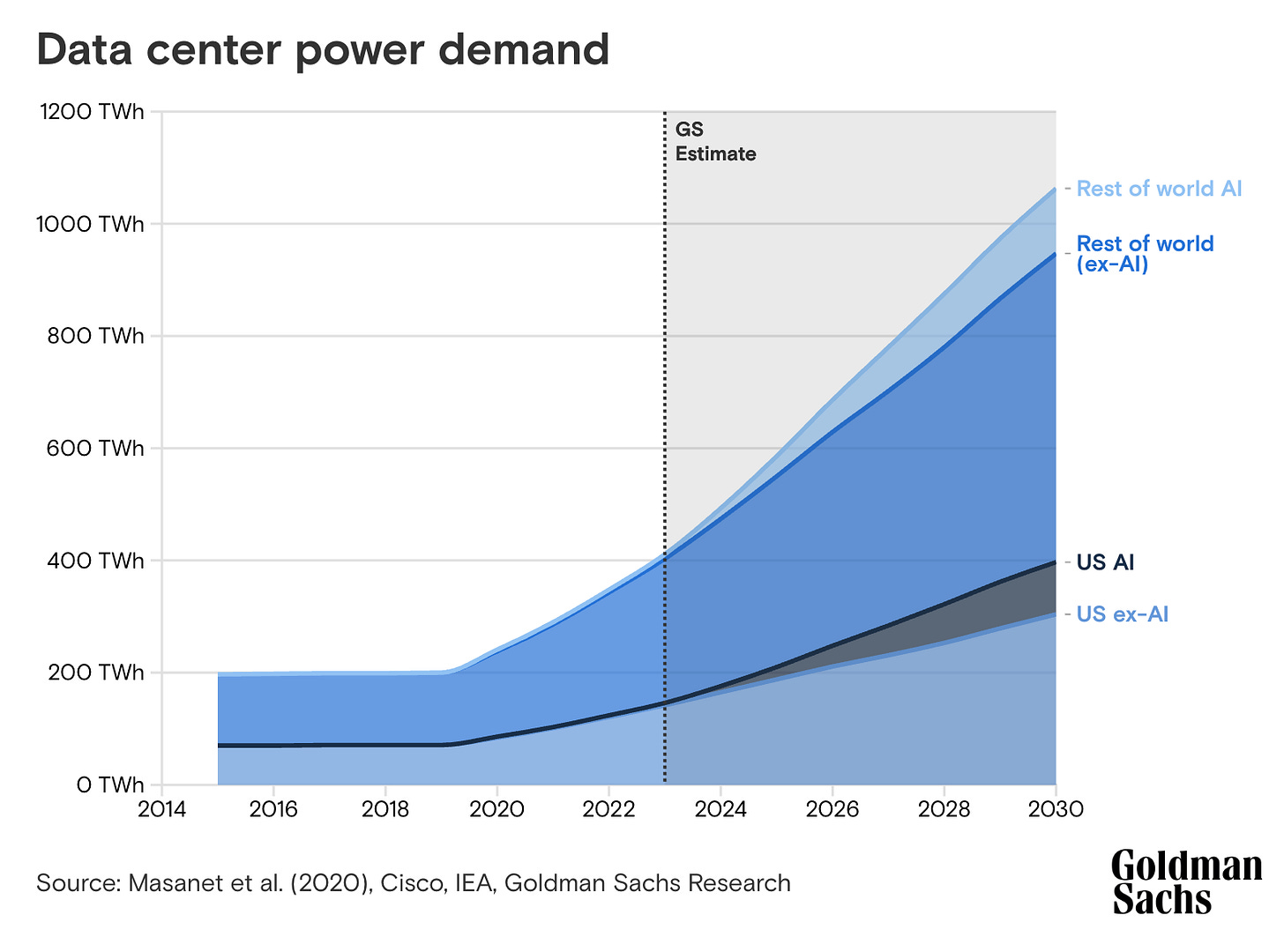

The statistic that data centers will be 9% of the US/21% of the global energy grid by 2030 is also widely misunderstood. People often see these numbers reported in articles about AI, and assume that all of that increase will come from AI. This is not the case:

Even the article I took this graph from is titled “AI to drive 165% increase in data center power demand by 2030.” I think what’s happening in the discourse is a lot of people regularly see titles like that, assume that AI is not only “driving” the 165% increase but is the only cause, and that ChatGPT is the main reason AI energy use is increasing. Both of these are wrong. According to the graph above, AI will contribute ~200 of the ~650 TWh of energy increase in data centers. The rest will come from more people accessing the internet and other data center services. By 2030, AI will be about 20% of the energy used in data centers, and if trends hold chatbots will be about 3% of that energy, or 0.6% of the energy used in data centers. Since data centers will use about 20% of the world’s energy, ChatGPT and other chatbots will use about 0.12% of the world’s energy. It’s estimated that YouTube currently uses 1% of the world’s energy, so if AI grows at the rate experts expect, by 2030 chatbots will use about 1/10th as much of the global energy budget as YouTube’s current share. If you’re concerned about ChatGPT, you should be at least ten times as concerned about YouTube.

Obviously both of these would be a waste of time for the environmental movement. There are much bigger culprits in global emissions (our food systems, transportation, and failing to switch to green energy sources) and therefore much more powerful levers we can pull to save the climate.

Water use

Why do LLMs use water? Where does it go after?

Here’s ChatGPT’s explanation of why and how AI data centers use water and where it goes after. In a nutshell, AI data centers:

Draw from local water supplies.

Use water to cool the GPUs doing the calculations. GPUs in data centers heat up when active in the same way the GPU in your laptop heats up. Just like your laptop uses an internal fan to cool it down, data centers need to rely on a cooling system for their GPUs, and that involves running water through the equipment to carry heat away.

Evaporate the water after, or drain it back into local supplies.

Something to note about LLM water use is that while much of the water is evaporated and leaves the specific water source, data centers create significantly less water pollution per gallon of water used compared to many other sectors, especially agriculture. The impact of AI data centers on local water sources is obviously important to think about and how sustainable they are mostly depends on how fragile the water source is. Good water management policies should help factor in which water sources are most threatened and how to protect them.

How to morally weigh different types of water use (data centers evaporating it vs. agriculture polluting it) seems very difficult. The ecosystems affected are too complex to try to put exact numbers on how bad one is compared to the other. I will say that intuitively a data center that extracts from a local water source but evaporates the water unpolluted back into the broader local water system seems bad for very specific local sources, but not really bad for our overall access to water, so the whole concern might be really overblown and wouldn’t matter at all if we just built data centers exclusively around stable water supplies. I’m open to being wrong here and would be excited to get more thoughts in the comments. Simply reporting “Data centers use X amount of water” without clarifying whether the water is evaporated, or returned to the local water supply polluted or unpolluted seems so vague that it’s a bad statistic without more context.

An important fact many people talking about LLM water use don’t seem to know is that basically everything in America that uses energy uses water, because most of the way we generate energy is by heating water into steam to spin magnets around wires. Each year, America “uses” 60,000,000,000,000 (60 trillion) liters of water to generate electricity. That’s about 3 times as much water as the Great Salt Lake. I put “uses” in quotes here because the water is continuously recycled. America doesn’t lose 3 Great Salt Lake’s worth of water each year due to our energy sector, and it also doesn’t lose 200 Olympic swimming pools of water every day due to ChatGPT.

How much water do LLMs use?

There’s a commonly cited statistic from the Washington Post that LLMs use a whole bottle of water to type a 100 word email. This statistic is almost certainly wrong, I explain why here. The more likely amount of water used is: 20-50 prompts on ChatGPT use the same amount of water as a normal water bottle (0.5 L).

This number can be deceptive however, because most of that is water is not used in the data center itself.

The study that gave us the number did not just measure the water used by data centers on ChatGPT searches, it also divided the water consumed by training into each prompt and the water used to generate the electricity used by the data center in the first place:

If you look at the “Water for Each Request” section in the top right of the table, only about 15% of the water used per request is actually used in the data center itself. The other 85% is either used in the general American energy grid to power the data center, or is from the original training (divided by the number of prompts). If someone reads the statistic “50 ChatGPT searches use 500 mL of water” they might draw the incorrect conclusion that a bottle of water needs to flow through the data center per 50 searches. In reality only 15% of that bottle flows through, so the data center only uses 500 mL of water per 300 searches.

All of this information is for GPT-3, not 4 or 4o. Because water used in data centers seems to be a mostly direct function of how much energy is used (because the water is cooling the equipment after it generates heat from using electricity), and 4 and 4o seem to use less energy per prompt than 3, we can assume “20-50 prompts = 500 mL of water used” is a reasonable upper bound guess for current ChatGPT prompts.

The average amount of water used to generate 1 kWh of energy in the United States is between 1-9 L. This means that the average household in America (using 900 kWh of energy monthly) is using between 900 and 8100 L of water to generate its electricity each month, enough water for 90,000 - 810,000 ChatGPT searches. I worry that including the water used in energy generation for ChatGPT searches can be misleading because people might not know that their everyday energy use also consumes huge amounts of water, and most of the water cost of ChatGPT is measuring that same type of water use, not some special use of water that happens in data centers. Using the same methods as this study, I could correctly say that your digital clock is using between 9 and 81 liters of water each year (as much as 50,000 ChatGPT searches if we only include the water used in data centers), but this would be deceptive if you had a reason to think the clock itself were using water internally. If we assume every other American uses a digital clock, then American digital clocks are using at minimum 1100 Olympic swimming pools of water each year. That’s a shocking statistic if we don’t contextualize it with how much water is used in our energy system in general. The American energy sector as a whole uses 60 trillion liters of water each year, enough for 25 million Olympic swimming pools. ChatGPT is using 1,500 Olympic swimming pools of water (with the water used for energy included), or 0.006% of America’s total water used for energy. For a service that’s used by as many people as the population of America multiple times every day, that seems pretty water efficient! It’s hard to think of other things 300,000,000 people could do every single day that would use less water.

If you’re curious about why it requires so much water to generate electricity, it’s that most of our electricity sources are based on heating water to spin magnets around wires.

The amount of water use by LLMs can seem like a lot. It is always shocking to realize that our internet activities actually do have significant real-world physical impacts. The issue with how AI water use is talked about is that conversations often don’t compare the water use of AI to other ways water gets used, especially if we use the methods for measuring it that the original study used.

All online activity relies on data centers, and data centers use water for cooling, so everything that you do online uses water. Further, if we use the same method as the original study, the water use of most online activity triples, because most of the water is in energy generation. The conversation about LLMs often presents the water they use as ridiculous without giving any context for how much water other online activity uses. It’s actually pretty easy to calculate a rough estimate for how much water different online activities use, because data centers typically use about 1.8 liters of water per kWh of energy consumed. This number includes both the water used by the data center itself and the water used in generating the electricity used (just like the original study on LLM water use). Here’s the water used in a bunch of different things you do on the internet in milliliters:

10 mL - Sending an email

10 mL - Posting a photo on social media

20 mL - One online bank transaction

30 mL - Asking ChatGPT a question

40 mL - Downloading a phone app

170 mL - E-commerce purchase (browsing and checkout)

250 mL - 1 hour listening to streaming music

260 mL - 1 hour using GPS navigation

430 mL - 1 hour browsing social media

860 mL - Uploading a 1GB file to cloud storage

1720 mL - 1 hour Zoom call

2580 mL - 10 minute 4K video

After the recent California wildfires I scrolled by several social media posts with over 1 million views each saying something like “People are STILL using ChatGPT as California BURNS.” They should have focused their anger more on the people watching Fantastic Places in 4k 60FPS HDR Dolby Vision (4K Video).

Should the climate movement start demanding that everyone stop listening to Spotify? Would that be a good use of our time?

What about the water cost of training GPT-4? So far I’ve only included the cost of individual queries. A rough estimate based on available info says GPT-4 took about 250 million gallons of water, or about 1 billion liters. Taking from the assumption above that ChatGPT has received about 200 billion queries so far, the training water cost adds 0.005 L of water to the 0.030 L cost of the search, so if we include the training cost the water use per search goes up by about 16%. That’s still not as water intensive as downloading an app on your phone or 10 minutes of streaming music. Remember that ChatGPT is just one function that GPT-4 is used for, so the actual water cost of training per ChatGPT search is even lower.

Animal agriculture uses orders of magnitude more water than data centers. If I wanted to reduce my water use by 600 gallons, I could:

Skip sending 200,000 ChatGPT queries, or 50 queries every single day for a decade.

Skip listening to ~2 hours of streaming music every single day for a decade.

I don’t think I’ll send 200,000 ChatGPT prompts in my lifetime. I’ve been vegan for 10 years, so I’ve skipped a lot of burgers. Each time I choose a vegan burger over a meat burger, I use at least 90% less water. Each individual meat burger I swapped for a vegan burger saved more water than I could save in a lifetime of avoiding ChatGPT. If the climate movement can have the same impact by convincing someone to skip a single burger as they can by convincing someone to stop using ChatGPT for 100 years, why would we ever focus on ChatGPT?

A common criticism of the above graph is that water cows consume exists in grass while water used in data centers is drawn from local sources that are often already water strained. This is not correct for these reasons:

About 20% of US beef cows are in Texas, Colorado, and California. Each state has experienced significant strains on its water resources. Approximately 20% of U.S. data centers draw water from moderately to highly stressed watersheds, particularly in the western regions of the country, so on this it seems like both industries have roughly 20% of their total activity concentrated in places where they may be harming local watersheds.

Data centers pollute local water supplies significantly less than animal agriculture.

As explained above, data centers built in water-poor areas probably use up drastically less water because they can rely on solar power.

If you are trying to reduce your water consumption, eliminating personal use of ChatGPT is like thinking about where in your life you can cut your emissions most effectively and beginning by getting rid of your digital alarm clock.

A back of the envelope calculation tells me that the ratio of water use of 1 ChatGPT search compared to 1 burger is the same ratio as the energy use of a 1 mile drive in a sedan compared to the energy used by driving the world’s largest cruise ship for 60 miles.

If your friend were about to drive their personal largest ever in history cruise ship solo for 60 miles, but decided to walk 1 mile to the dock instead of driving because they were “concerned about the climate impact of driving” how seriously would you take them? The situation is the same with water use and AI chatbots. There are problems that so completely dwarf individual AI water use that it does not make sense for the climate movement to focus on individual AI use at all.

The people who are trying to tell you that your personal use of ChatGPT is bad for the environment are just fundamentally confused about where water (and energy) is being used. This is such a widespread misconception that you should politely but firmly let them know that they’re wrong.

Thanks for writing this, Andy! A point worth sharing here is that the environmental critique of LLMs seems to have been "transferred" from the same critique of blockchain technology and NFTs. An environmental critique of NFTs is, as far as I know, valid — selling 10 NFTs does about as much harm, measured in carbon emissions, as switching to a hybrid car does good. What may have happened is that two coalitions that were arguing with each other about one technology simply reused the same arguments when a newer, reputedly-energy-intensive technology came around.

This hypothesis is not my own, but it strikes me as extremely plausible. I couldn't see how otherwise critics of AI could have anchored on this argument, when there are many other perfectly valid arguments about the downsides of LLMs!

Great article, but this also contains some zombie facts about older models that consumed way more energy - the costs keep coming down over time. https://simonwillison.net/2024/Dec/31/llms-in-2024/#the-environmental-impact-got-much-much-worse