Replies to criticisms of my posts on ChatGPT & the environment

Why I used 3 Wh, and why I don't say "Every Watt-hour matters"

My last post on ChatGPT got more attention and some criticisms from people concerned about ChatGPT’s climate impacts. I’m going to collect and reply to criticisms here. If I added these to the original posts it would get too long, so I’m keeping them separate. If you’d like me to reply to any other criticism, share in the comments or email me at AndyMasley@gmail.com.

Factual disagreements

3 Wh is useless as an estimate because we don’t actually have any idea how much energy ChatGPT uses. This is all meaningless guesswork

This came up as the most common criticism of my post: we don’t actually know for sure how much energy chatbots are using, because the big AI labs aren’t telling us, and 3 Wh was originally a random guess, so an entire blog post extrapolating that number is completely useless. This is meaningless guesswork.

I’ll explain why I disagree.

Where did 3 Wh come from? Why did I use that as my number in my post?

It’s hard for me to find where it was first suggested that the average ChatGPT prompt uses 3 Wh. Some have pointed out that it seemed to come from an offhanded comment a tech CEO made about ChatGPT using “about 10 Google searches’” worth of energy, and people extrapolating that offhanded comment.

The reason I chose 3 Wh as the number for my post wasn’t that I think it’s the definitive final answer for the cost of a ChatGPT prompt, it’s that every serious attempt at estimating the average ChatGPT prompt’s energy use I’ve seen finds that it’s below 3 Wh, so I ran with that as a reasonable upper bound. Here are a few example estimates I could find, each using a different method of guessing the energy cost of a ChatGPT prompt at the time:

Aug 2023: 1.7 - 2.6 Wh - Towards Data Science

Oct 2023: 2.9 Wh - Alex de Vries

Feb 2025: 0.3 Wh - Epoch AI

May 2025: 1.9 Wh for a similar model - MIT Technology Review

June 2025: Sam Altman himself claims it’s about 0.3 Wh

This post is a pretty good summary of the (surprisingly sparse!) data on ChatGPT’s energy use. It comes to the conclusion that ChatGPT still uses 10x as much energy as a Google search, but both ChatGPT and Google use 10x less energy than commonly assumed, so ChatGPT probably uses around 0.3 Wh per prompt and a Google search uses 0.03 Wh.

This tool from Hugging Face shows the energy a chatbot uses for any prompt you give it. It’s not ChatGPT, but you can see that for almost all prompts it falls way below 3 Wh for similar answers.

Here’s a response from Gemini’s Deep Research going into a lot more detail about what we know about how much energy individual ChatGPT prompts use and how uncertain we are.

The Washington Post/Shaolei Ren massive outlier

There’s one massive outlier: The Washington Post cites Shaolei Ren’s estimate that an average ChatGPT prompt (writing a 100 word email) uses 140 Wh, and a bottle of water. Ren had previously co-authored a paper on GPT-3’s water use, implying that it uses 500 mL of water per 20-50 prompts, so this would be a 20-50x increase for GPT-4. This is MUCH larger than the other studies. I wanted to see what Ren did differently to figure out how much I should update, and came away skeptical.

The 140 Wh figure isn’t in any of Ren’s peer-reviewed papers. It only appears in a Washington Post graphic with no accompanying methodology. That alone makes it hard to evaluate. The number fails two basic sanity checks:

It implies each prompt ties up a whole GPU server for 30–60 seconds (10 kWh server = 2.7 Wh per second, so hitting 140 Wh would take about 50 seconds). But ChatGPT usually responds in 1–2 seconds, and data centers don’t dedicate an entire 10 kW DGX box to a single user. In reality, inference is batched (production systems like Azure see 10–30% average utilization) and the GPU’s energy cost is amortized across multiple simultaneous prompts. 1-2 seconds on an entire 10kW GPU server would use up 2.7-5.4 kWh.

The article claims GPT-4 “can use 60× more energy than GPT-3.” That doesn’t match what we know. GPT-4 is a mixture-of-experts model, so only a subset of the full model runs on any given prompt. The actual active parameter count is likely 2–5× larger than GPT-3, not 60×. I’m not sure where so much additional energy would be coming from.

The 140 Wh figure feels like what you’d get if you assumed a whole server was burning full power just to write you an email: no batching, no amortization, no realistic deployment assumptions. It seems like that might’ve been the assumption Ren made. I don’t know, because I can’t find the methodology anywhere and it wasn’t peer-reviewed.

All of this made me more confident in sticking with 3 Wh as a conservative ceiling. It’s easy to defend and consistent with a wide range of independent methods. I don’t really understand how Ren got these numbers and don’t see how they would be possible.

This is a great thread going into specifics about why we basically shouldn’t update on this study.

Conclusion

So I disagree that this is vibes and guesswork. It’s very uncertain! But people more knowledgeable than me have tried their best to put a number on the energy and water involved, so it’s more than a random shot in the dark. I’ve tried to defer to where all their guesses are. Almost all conversations about individual climate impacts from using ChatGPT seem to assume the same numbers are correct, so this is what’s being debated. We could all be wrong, but it seems just as likely that ChatGPT actually uses less energy than that it uses more. Given that we’re uncertain, and a lot of people are still making strong claims that ChatGPT is terrible for the environment, I think I’m perfectly within reason to write about how the numbers we have strongly imply that they’re wrong.

What should we do if we’re uncertain?

The data here is pretty shockingly murky and unclear. I think the best move is to say “We know these numbers are unclear. Based on the best guesses that we have, this is what they imply about how bad ChatGPT is for the environment. That could change as new numbers come in and OpenAI releases new models that use different amounts of energy.” I tried to be clear in the posts that 3 Wh is the edge of a very murky uncertain range, not the absolute specific cost of every ChatGPT prompt.

Trying to figure out how much energy the average ChatGPT search uses is extremely difficult, because we’re dividing one very large uncertain number (total prompts) by another (total energy used). How then should we think about ChatGPT’s energy demands when we know almost nothing certain about it?

The people who believe that ChatGPT is uniquely bad for the environment are also basing their numbers on guesswork. If we can’t know anything about ChatGPT because the numbers are too uncertain, it doesn’t make sense to single it out as being uniquely bad for the environment. We just don’t know! Whenever people try to guess at the general energy and water cost of using ChatGPT, the numbers consistently fall into a rough range with an upper bound for the average prompt’s energy at about 3 Wh, so that’s what I’m running with. Maybe all these guesses are wrong, but we have just as much reason to believe they’re higher than the true cost of ChatGPT as we do that they’re lower.

If we can say anything at all about ChatGPT’s energy use, everything in my last posts is in line with our best guesses.

If we can’t say anything at all about ChatGPT’s energy use, you should be just as skeptical of claims that it’s bad for the environment, because its critics are also basing their claims on nothing but guesswork.

Saying “ChatGPT is uniquely bad for the environment” and then adding “And you can’t disagree with me because all numbers involved are based on guesswork. No one knows anything” is a pretty obvious double standard. If it’s all guesswork, no one can make any strong claims about ChatGPT and the environment. If we truly know nothing about it, it seems reasonable to assume it’s in line with every other normal thing we do online.

This number is constantly changing, but in both directions

In addition to this being a guess, this number is constantly changing as new models get released. There are reasons to expect it to increase and to decrease:

Increase: New models that use more energy intensive tools and processes, like chain-of-thought. O3 especially probably uses a lot more energy than 4o.

Decrease: AI companies don’t want to give too much energy to you for free. That would be like giving you lots of free money. Almost all ChatGPT users are free users. ChatGPT has 400 million weekly users, but only 11 million paid users. This means that 98% of ChatGPT’s users are being given free energy by OpenAI for their prompts. Google search now has an AI chatbot built in and is completely free. If either of these were giving you control over a significant amount of energy, this would basically be a massive free giveaway from the AI companies to billions of people. OpenAI and other AI labs have extremely strong incentives to make their models as energy efficient as possible.

ChatGPT’s critics have been somewhat silent on this number being “fake,” until now

For the last year I’ve seen the point “ChatGPT uses 3 Wh. That’s ten times as much as a Google search. That’s so much energy. We need to stop using it!” repeated everywhere. If you search YouTube or TikTok, almost every video mentions the 10x a Google search line. Obviously it’s possible everyone is wrong here, but it’s notable that public critics of ChatGPT’s energy use who are now saying the 3 Wh point is incorrect and “we don’t know how much it’s actually using” were pretty silent about everyone getting this wrong until I and others started to post more about how it actually implies ChatGPT is really not energy intensive compared to most things we do. This silence is a little odd and one-sided. If you think this is a bogus statistic, you also shouldn’t be tolerant of it being used to argue that ChatGPT is bad for the climate either.

It’s fine to say we can’t use the 3 Wh number, but please make sure to also shut down anyone using it to say ChatGPT is uniquely bad for the climate. If we’re so in the dark that we can’t say anything about it, we shouldn’t.

Isn’t it wild that so much of this is a massive game of telephone?

It’s wild how little info we have about this, and how the guesses that get made spread like wildfire and becomes common wisdom so quickly (I’ve seen Ren’s estimate that each ChatGPT prompt uses an entire bottle of water everywhere, but can’t find any info on where it comes from and it seems to contradict everything else we know). We could use more transparency from the labs and more people focused on fact-checking and updating these estimates. If you’re good at this kind of stuff, we could use your help!

3 Wh still adds up to enough to worry about (Ketan Joshi’s bizarre reply)

I think this response might be the single strangest I’ve ever received online, because it came from someone who seems to have a pretty big following as a climate communicator, and was more or less completely innumerate, to the point that I assumed it was in bad faith. I originally hadn’t mentioned that it was from Ketan Joshi but he seemed surprised that I didn’t, so I’m adding the link to the original. It was one of the most widely reacted-to replies to what I wrote:

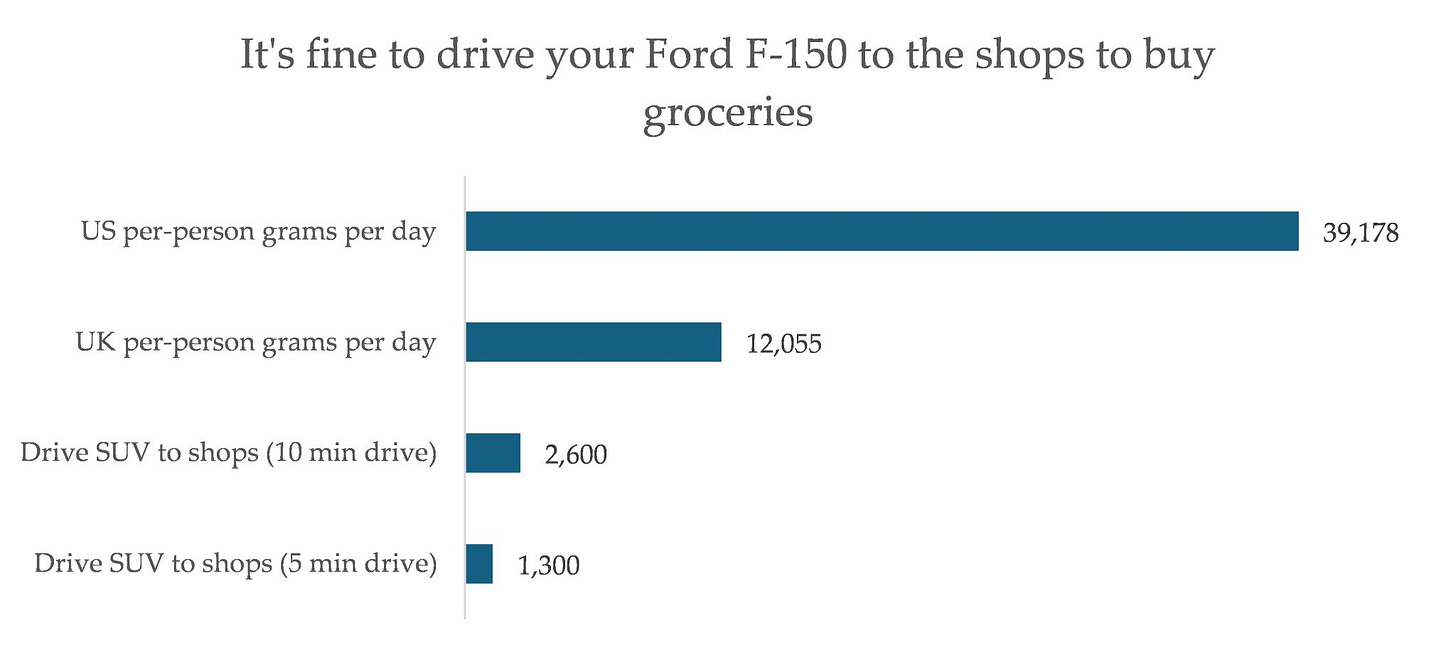

Most of my argument can be made by just including the emissions of 100 ChatGPT prompts on the emissions graph (assuming 3 Wh per prompt and the American average of 386 g of CO2 per kWh)

Does the average person prompting ChatGPT even use it 100 times per day? Here we actually have clear numbers. ChatGPT gets 400 million weekly users and 1 billion daily prompts, so the average person who uses ChatGPT is sending 2.5 prompts per day.

What about the most serious power users?

Here’s a thread on the “prompt engineering” Subreddit where people talk about using it between 100-300 times per day. People specifically on the “prompt engineering” subreddit responding to a thread about using it a lot are likely to be some of the heaviest users of chatbots, so it seems like 100-300 prompts per day is a reasonable upper bound for what most people are doing with ChatGPT.

Even this won’t get us to a comparable number to cars.

Prompting ChatGPT 300 times per day would be about 110,000 prompts per year. It would almost triple the size of the red bar on this graph:

That would be a lot, but almost all Americans drive waaaaay more than 5 minutes per day, so even tripling the size of the red bar wouldn’t get it anywhere near the car-free bar on the far left.

A climate communicator seriously arguing that chatbots have comparable climate impacts to cars is really bizarre to see. ChatGPT uses about 20,000 American homes’ worth of energy each day, globally. Cars in America alone (when you include commercial use) use more energy than all American homes. About 20,000x as much energy as ChatGPT uses globally. Here’s 20,000 dots:

The ratio between all ChatGPT prompts around the world and your individual home is exactly the same as the ratio between cars in America alone and ChatGPT’s global energy use (20,000:1). If you have any intuitions about how OpenAI’s energy use in all data centers for ChatGPT compares to your individual household’s energy use, that gives you some idea of how much bigger of a problem cars are compared to ChatGPT as a global problem.

The person who wrote this is correct that literally anything we do could add up to eventually be a more significant part of our energy budget if we use it enough. This is true of Google and gaming consoles and vacuums and microwaves and ChatGPT and Netflix. That idea on its own gives us no guidance for what to cut. It’s still often much easier to cut the things that use way more energy per second. At some point we need to ask how energy efficient the average’s persons’ different ways of spending time are. Asking and reading answers to 100 ChatGPT prompts would take me hours. I actually can't think of other activities I could spend whole hours on that would use less energy.

Fortnite uses at least as much energy as ChatGPT, and I think Fortnite is much more useless (or even actively harmful) compared to ChatGPT, but you don't see climate scientists arguing that we shouldn't use Fortnite, because there are so many better ways to cut our emissions.

He’s adding up the impact of doing a small activity a lot over the course of months (or across many people) to a big activity done a single time. As I said before, this is a really classic error in climate communication:

Everything else I’d say about this is already covered in these sections:

To be blunt, I don’t like people who are voices for the climate implying that basically anything we do online is in the same league as the unbelievable climate disaster that is driving. It would be really preferable if we electrified everything and relied a lot more on public transit. There’s basically no individual behavior that’s in the same order of magnitude as much of a climate emergency as driving, except flying.

It seems like Joshi’s identified AI as a bad guy (fair enough, for other reasons) and is responding with a not thought through response and he doesn’t actually care if the numbers are actually pointing at something real. I was disappointed that this was one of the most reacted to responses to the post.

Note: Since writing this, Joshi’s behaved in remarkably bad faith in general with my and other’s work to the point that I’ve decided he’s mostly just in this for attention. It’s important to not give bad faith actors more attention so I won’t be responding to future takes from him.

You conveniently left out ___

A lot of people would say things like “He conveniently left out” and then add some very specific environmental issue with ChatGPT, like future models, or how using ChatGPT normalizes AI more broadly.

If you notice that I’ve left an important piece of information out, it’s most likely because I don’t want the post to be even longer than it is, not that I’m dodging your objection. I’ve already written (by the standards of NaNoWriMo) half a novel’s worth of posts on ChatGPT and the environment. Writing about this stuff makes you realize just how intricately detailed it all is, because it touches on so many different questions at once (Does your personal carbon footprint matter or should we only look at big systems? Does every Watt-hour matter? How does AI work anyway? What other services use water in data centers? Is Epoch AI a reliable source?) etc. and there are so so many different things people can object to based on their perspectives about climate, ethics, tech, the value of AI, water use, electricity generation, and so much more. The whole subject starts to feel like a fractal.

If you think you have an important fact that flips my whole argument, please let me know! Email me or comment below. I was disappointed to see some people responding to my last two posts by just sharing them elsewhere and saying “This whole thing is a lie because he’s conveniently leaving out” x. If you actually think I’m forgetting something big, just let me know! But if you’re upset that I haven’t responded to the Jevons Paradox and its relationship to AI and energy, consider that it might just be that I want these posts to stay readable and not turn into long books. I’m happy to add your critiques here if you let me know.

Sometimes people would say “He conveniently left out the cost of training” even though I’d included clearly labeled sections about training in both posts. Turns out not everyone’s reading the posts they’re replying to.

Climate ethics disagreements

Every Watt-hour matters. People should still worry about ChatGPT because it uses energy at all

Another common response was that we should still worry about ChatGPT because “every Watt-hour matters.”

This sounds nice and noble, like a way of taking climate change maximally seriously, but it’s actually an extremely bad way to think. It leaves the climate movement open to becoming distracted when we have extremely limited time, and lots of ways we can completely fail to have a large impact.

The climate movement quantifying where it’s actually going to have the most impact is really really really really really really really really really really important.

Kate, Bob, and Freddy

Suppose there are 3 people who each want to have an impact on the climate: Kate, Bob, and Freddy. They each independently choose their own ways of impacting the climate. All seem really noble and self-sacrificial. Kate joins a committee of 500 people working for a year to keep a nuclear power plant open for another 10 years. Any impact they have will be divided by 500 people. Bob goes vegan for a year. Freddy has a debilitating ChatGPT addiction and prompts it 300 times per day. One prompt every 3 minutes every waking hour. He quits for a year.

Try to form an idea in your head of how their climate impact compares to each other. It’s not immediately obvious.

After 1 year, Kate has prevented 70,000 tonnes of CO2 from being emitted. Bob has prevented 0.4 tonnes. Freddy prevented 0.2.

This means that Kate had as much effect as 175,000 Bobs, or 350,000 Freddys.

Here’s how many people would need to go vegan for a year to match Kate’s impact:

I worry that when people sneer at quantifying climate interventions, they don’t realize how gigantic the differences are in what we can do.

Choices for where to work on climate to help the most don’t take too long to make. You can just do some research and see for yourself where the most promising places to work are. When you do that, you don’t double or triple your impact; you multiply it by the population of an entire city. It’s as if you create an entire new city of climate activists just by taking a little extra time to look around for the best places to help.

If we could convince 50,000 people to just stop and look around for the most impactful things they could do for climate in the way Kate did, it would have the same impact as convincing the entire world to go vegan.

The slogan “Every Watt-hour matters” implies something really dangerous. It implies that because Bob and Freddy were making any adjustments in their lifestyles that reduced emissions at all, they were contributing to end the climate crisis. Compared to Kate, their efforts rounded to zero. They became distracted by super low impact methods for an entire year, when they could have had as much impact as entire cities of people. Going around and telling people who care about the climate that they should use their limited time and energy to worry about ChatGPT is a bad distraction from actions that can do literally millions of times as much good.

The climate movement drastically needs millions of Kates, now. We need to get the message across that what you do for the climate can by any normal measure have millions of times as much impact if you just stop for a moment to try to think about what’s actually going to make a difference. What we absolutely do not need is messaging that says “No matter what you’re worried about, if it uses energy, that’s a legitimate thing to put time and thought into for the sake of the climate.” We don’t have time for that.

We’re running out of time

When I first became interested in climate in 2007, the dream was still alive that we could avoid 1.5 degrees of warming by 2100. That dream is effectively dead. We lost. We didn’t hit the deadline. We’re almost definitely going to hit 1.5 degrees of warming. This doesn’t mean we should give up. The future victims of climate change are owed our hard work. We can still avoid 2 degrees of warming by 2100 if we act aggressively. In my time following the climate movement I’ve seen the tragedy of our great collective failure to hit our first target.

This graph shows what global CO2 emissions need to do to avoid 2 degrees of warming:

The sooner we start making significant cuts to global emissions, the better. I don’t know how you can look at a graph like this and say “The climate movement should spread messages about focusing on cutting any activity, no matter how few Watt-hours it uses. Its members should spend their time and energy on anything that uses energy.” There are too many ways to have a ton of impact (and too many ways to miss them) to justify thinking this way.

It makes much more sense to say “We are basically in a very fast-moving battle against an incredibly complicated impersonal enemy who doesn’t care at all about the personal virtue of each of our soldiers. We need to deploy each person we have on our side to where they can do the absolute most good for the climate. Just having them all go off and focus on their own vibey thing as long as it cuts Watt-hours at all isn’t going to cut it at all. We’ve already had some massive losses and are on track for way more.”

Toward David MacKay thought

The text that’s influenced how I think about climate communication more than any other is Sustainable Energy - Without the Hot Air by David MacKay. If you read it, you’ll recognize that I was trying my best to imitate MacKay’s style in my last two posts. This quote is long but worth reading in full. It was written 16 years ago but is just as applicable today:

This heated debate is fundamentally about numbers. How much energy could each source deliver, at what economic and social cost, and with what risks? But actual numbers are rarely mentioned. In public debates, people just say “Nuclear is a money pit” or “We have a huge amount of wave and wind.” The trouble with this sort of language is that it’s not sufficient to know that something is huge: we need to know how the one “huge” compares with another “huge,” namely our huge energy consumption. To make this comparison, we need numbers, not adjectives.

Where numbers are used, their meaning is often obfuscated by enormousness. Numbers are chosen to impress, to score points in arguments, rather than to inform. “Los Angeles residents drive 142 million miles – the distance from Earth to Mars – every single day.” “Each year, 27 million acres of tropical rainforest are destroyed.” “14 billion pounds of trash are dumped into the sea every year.” “British people throw away 2.6 billion slices of bread per year.” “The waste paper buried each year in the UK could fill 103448 double-decker buses.”

If all the ineffective ideas for solving the energy crisis were laid end to end, they would reach to the moon and back.... I digress.

The result of this lack of meaningful numbers and facts? We are inundated with a flood of crazy innumerate codswallop. The BBC doles out advice on how we can do our bit to save the planet – for example “switch off your mobile phone charger when it’s not in use;” if anyone objects that mobile phone chargers are not actually our number one form of energy consumption, the mantra “every little bit helps” is wheeled out. Every little bit helps? A more realistic mantra is:

if everyone does a little, we’ll achieve only a little.

“Everyone should do their part and avoid prompting ChatGPT” being argued 15 years after this was written makes me want to throw my hands up and say “Look at my climate movement dawg, I’m never getting below 2 degrees of warming by 2100.”

Comparing Watt-hours to money

The median American salary is $61,984 per year. The average American uses 10,700 kWh of energy per year. This means that spending 1 Watt-hour on our energy budget is like spending $0.006 for the average American (it’s the same ratio). So if you’re budgeting your energy, and you’re the average American, adding 1 Watt-hour to your energy budget is like adding half a cent to your literal budget. Hearing climate communicators say “every Watt-hour matters” sounds kind of like someone who is worried about the national debt saying “Americans should save more, every half a cent matters!” That’s obviously hyperbole designed to make a point. It’s not literally true that people worried about the national debt should actually be worried about every individual time they spend a single penny, and the same is true for the climate movement and Watt-hours. Watt-hours are the pennies of our energy budgets.

It doesn’t make sense to separate ChatGPT from other uses of generative AI

This is an interesting philosophical question. It’s pretty thorny and hard to address conclusively. Using chatbots on their own might not use much energy, but they both normalize AI and ChatGPT is just one small part of generative AI’s overall footprint.

One interesting point here is that the majority of ChatGPT’s users are free-tier users. ChatGPT seems to have about 11 million paid users, and around 400,000,000 weekly users in total. This means that for almost everyone using ChatGPT, there’s a sense in which they’re hurting OpenAI by adding to its energy and water costs, rather than supporting the company. They’re also normalizing ChatGPT use, which OpenAI clearly seems to think is worth the trade-off.

I think when most readers ask the question “Is it bad for the environment when I do x?” they’re not usually asking about the second or third order effects of their actions. These obviously matter, but including them in our calculations would add a crazy amount of uncertainty and also increase the emissions of everything else we do by a comparable amount.

For example, every time I drive to the store, I use gas and emit CO2. I know exactly how much I emit and can use that to calculate how bad it is for the environment. Every time I drive, I also normalize driving. The people around me adjust a tiny little bit to thinking driving is normal. They might do it a little more. It seems hard to quantify this, and for most things we do we’re not asked to quantify this kind of thing to address whether it’s bad for the climate or not.

I think my readers are smart enough to understand that I’m making a point about the specific energy costs they create when they use chatbots as individuals. What they normalize and contribute to more broadly is more of a question of whether boycotting OpenAI and other AI labs makes sense as a way of sending a message about generative AI’s overall impact. I’m not sure that it does. It seems like a much more effective way of protesting would be supporting and writing about specific policies around energy, water use, and other issues around AI and the climate. With 1 billion daily prompts, it’s hard to imagine individual boycotts having too much of an impact.

Personal attacks

You just want to use ChatGPT!

I’m pretty good at boycotting things that I think are doing harm. I’ve been vegan for 10 years and don’t drink because of alcohol’s impact on society. I really like meat and alcohol! I’d rather consume them if I thought it was okay! ChatGPT would be super easy to give up compared to both.

The causality people are assuming here goes like this:

I like ChatGPT → I invent reasons why it’s okay to use → I don’t think ChatGPT is bad for the climate

It seems like they have a hard time imagining that I do just believe the arguments I’m making, and the causality looks like this:

I don’t think ChatGPT is bad for the climate → I use it → I like ChatGPT

I think in general people often over-psychologize other people they disagree with. It seems hard for some people to imagine actually believing ChatGPT might not be that bad for the climate, so they assume I must have some ulterior motives for posting about it. If they just looked at the arguments directly, I think we could have more useful disagreements. Debating about what’s in my head or my secret motivations for this feels silly.

It’s especially strange to listen to adults talk about my dark ulterior motives for wanting to use 3 Wh of energy at a time. I made this list of other things 3 Wh can do. If people were talking about my dark ulterior motives for using a microwave more often, I would think something really strange had happened to the climate movement.

You’re a climate denier!

If I thought climate change were fake, it seems pretty easy to just say so directly. I could call my post “Using ChatGPT isn’t bad for the environment because nothing is bad for the environment!”

I’ve been worried about climate change for almost 20 years. Climate communication was a big reason I originally became a physics teacher. If you talked to any of my former students, they’d report that I was constantly bringing up how class material related to climate change. Here’s a lecture I made six years ago for them on how climate change works.

I’m worried that some people in the climate movement have developed a really bad habit of calling other people climate deniers over extremely minor disagreements about where we should be focusing our attention. In any other community this would be obviously bad.

In 2024 I thought it was really really really important that Harris win the election. I knew a few people who were voting for the Green Party instead. I disagreed with their decision, and I think that decision was extremely bad for the climate, but I wouldn’t call them climate deniers. They obviously care a lot about climate, we just had disagreements over other facts and values about the world. Specifically, the trade-offs of a protest vote against the Democrats vs. the risk of another four years of Trump. Calling them climate deniers wouldn’t have been true, and it would’ve made the conversations between us much worse.

Any good faith reader of my post would recognize quickly that I take climate change really seriously and the whole point of the post was to argue that the climate movement is getting distracted. I think anyone calling people climate deniers over minor disagreements about where to spend our attention and energy are just incredibly bad for the movement. They’re both diluting the meaning of the insult and making it impossible for the climate movement to adjust to new arguments and disagreements.

In general there’s a lot of pointless random attacks that happen in the climate space like this. Makes me sad! It’s an example of the bad way of thinking about climate I had mentioned in my first post:

To think and behave well about the climate you need to identify a few bad individual actors/institutions and mostly hate them and not use their products. Do not worry about numbers or complex trade-offs or other aspects of your own lifestyle too much. Identify the bad guys and act accordingly.

Every time I see behavior like this, my first thought is “Look at my climate movement dawg, I’m never getting below 2 degrees of warming by 2100.”

You’re an effective altruist!

Yes. I don’t exactly hide this. I run the EA DC city group and mention it in my about section on this blog. Learn more about EA here. I’ve been into and involved in EA in different ways since college, and the background ideas since 2009. Here are some of my thoughts on EA. This doesn’t really affect how I think about ChatGPT’s energy impact.

If you hate effective altruism and think this is all bad, I tried to write the original post so that this wouldn’t matter at all. We don’t need to agree on any of this to agree on literally everything I wrote there.

There were a few implications that because I’m into EA, I must think climate change is fake. I’m not sure why people jump to this conclusion. Everyone I know who’s into EA thinks climate change is real and a serious problem.

The idea that EAs think climate change is fake comes from an idea that we think everyone should be working on catastrophic risk from advanced AI instead. This isn’t the case. There’s a lot of debate and disagreement within EA networks about what should be focused on, and a big climate community. The basic EA argument for working on AI risks over climate is that between climate and AI catastrophic risk, AI risk has way way way way fewer people working on it. There are reasons to think this lack of people is a massive problem, because the scale of the risk could be large. If you disagree, that’s fine! But this belief isn’t exactly “climate denialism.”

I can understand having a very negative reaction here and saying “Some EAs are prioritizing a speculative future risk over much more concrete harms.” I have to bite the bullet and say I think risks from AI are worth worrying about. If you disagree that’s fine, but if you’re interested in the arguments for why I’d ask you to just read this article.

This 80,000 Hours post on working on climate change made basically the same point. It’s often used as an example by critics of how EAs don’t take climate seriously. If you actually read the article, the point being made is that climate change is a gigantic global problem that deserves a lot of people working on it, and the 80,000 Hours crew just think that between climate change and their other main problem areas (AI risk, global pandemics, nuclear war, great power conflict, and animal welfare) an additional person can probably have more impact choosing one of their other much more neglected cause areas, because climate is already so focused on. The article basically says “We defer to the IPCC report’s predictions for how bad climate change will get, and compare that to risks from nuclear war or global pandemics or AI risk. Based on this comparison it seems like the average highly qualified person could save more lives prioritizing one of these other cause areas.” This isn’t exactly climate denialism.

I didn’t write the posts to say that no one should worry about climate change. I try to say repeatedly that I think worrying about ChatGPT’s environmental impact is bad if you take climate change seriously, because ChatGPT is basically a non-issue that’s going to distract the climate movement from the very real serious problems coming our way. Nowhere in either post do I say “You should really work on speculative AI risk instead, climate change is fine!” because I don’t believe that. I’m trying to use the post to convince people to focus on systematically changing our energy grid over insignificant lifestyle changes, and if they do think about personal consumption choices, to focus on flying, driving, switching to green energy, and eating less meat.

If you’d like to learn more about how EAs think about and work on climate change, I’d strongly recommend the Effective Environmentalism page.

You don’t have a background in AI!

This is correct. I basically just read about AI as a hobby. I’m not actually making any new claims about how AI works in these posts, or claiming to be an expert, or to know more about it than experts.

I majored in physics and then taught it for 7 years. I do have some expertise in energy. I see this debate as kind of like a debate about budgeting money. We’re trying to work out where it makes the most sense to reduce our spending (with energy instead of money). I see AI as one thing we can spend our personal energy budgets on. It’s like gum balls. The people who have expertise in AI are like people who know a lot more about the process of making gum balls, the different flavors, their history, how different communities interact with them. I’m like someone who’s been studying and teaching the overall nature of money in general. I can step in from the outside, and say “Hmmm, well I don’t actually know much about the intricacies of gum balls, but if all the numbers people keep using as the price of gum balls are correct, these just don’t matter for our budget much compared to most of the other things we do. I can point to all the other ways we use a lot more money and what that means for our overall budget situation.” So I am claiming expertise in what energy is and where it’s used in society. There the playing field between me and AI experts is equal.

This is just a Substack post, not a peer-reviewed paper

I don’t think people making this claim know what peer review is (or maybe they’re just not actually reading the posts). A claim only needs to be peer reviewed if it’s something new that we don’t already know that hasn’t been verified by other studies. In these posts, I’m taking the numbers that we’ve been given by peer-reviewed studies or that are our best guesses, and saying “if these are true, this is how the energy costs of ChatGPT compare to other things we do.” I’m never once saying “I’ve discovered something special about ChatGPT that others haven’t noticed.” I never make any big scientific claims about how ChatGPT works or how much energy it’s using. I defer to others and express uncertainty when it shows up.

Why I started posting about ChatGPT’s energy use

I want to make something clear about why I decided to post about this more, because a lot of people were implying I have some nefarious connection to the AI labs. It’s fun to imagine being evil or a part of some big conspiracy, but the reality’s pretty boring: I was motivated entirely by a deep sense of unease as a former physics teacher that so many people were speaking in such apocalyptic tones about such small amounts of energy.

I would go to parties, ChatGPT would come up, people would say “Oh it’s awful for the environment. It’s ten times as bad as a Google search.” I had spent the last seven years of my life explaining to children how much energy a Watt-hour is, so I felt like it would make sense to explain my perspective. I would start to say “Oh I mean that’s probably true, but that’s really not very much energy! Here are a few exa-” but before I could continue the person I was talking to would start accusing me of being an apologist for OpenAI or a tech bro etc. This experience was eerie and disorienting! This grown adult standing across from me was suddenly talking in this distrustful conspiratorial way about something I’d spent so much time talking about with my students. My students understood this all much better! I found that it was hard to get across the basic intuitions without the conversations turning sour. I was also starting to see really bad interpretations of statistics like “Every 20 ChatGPT searches use a whole bottle of water, that’s so much!” all over social media. I wanted a place to point people to with lots of images and intuitions for how much energy and water chatbots use compared to other things we do, which is why I wrote the original post.

Here’s a recent Twitter post that got 100,000 likes and 3 million views. I would hope that critics of ChatGPT’s climate impacts would still agree that posts like this are wildly misleading and giving young people an incredibly incorrect idea of what in society is actually threatening the climate and straining our energy systems. Seeing this tweet get popular made me feel vindicated in posting about this recently. There are still drastic popular misconceptions about this everywhere, and it at least nice to read this knowing I had already covered everything said here in my last two posts.

It is deeply unacceptable that the contents of this post are considered common knowledge by a lot of people who identify with the climate movement. They’ve been tricked, and they deserve to know what’s actually up.

For people who it isn’t as black and white as Kate’s option of joining a committee, what do you suggest doing for the environment. I understand your take on how being vegan or not using ChatGPT would make less change, I mean it all makes sense and I agree. But it does leave me wondering thinking, what can I do? Of course I could still be vegan or try lessen my carbon footprint but that won’t be doing much. What are some suggestions that you would say would help the environment more efficient. Preferably if you could come up with a variety of solutions it would be great, but I do understand that I should maybe do my on research on the topic instead of trying to quickly find answers.

It was funny seeing Ketan Joshi's name pop up again here: he's a deeply disingenuous commentator who mostly just looks for excuses to trash on people or ideas not in his clique. His whole exchange w/ Jordan Shanks some years back really highlighted the kind of person he is.