Using ChatGPT is not bad for the environment - a cheat sheet

The numbers clearly show that discouraging people from using chatbots is a pointless distraction for the climate movement

This post will be a cheat sheet for answering every environmental objection to using ChatGPT. I’ve broken it up so you can skip around and only read sections relevant or interesting to you. If you think I’m getting anything wrong I’d be excited to update this with the most accurate numbers. Please let me know in the comments or at AndyMasley@gmail.com.

Intro

The question this post is trying to answer is “Should I boycott ChatGPT or limit how much I use it for the sake of the climate?” and the answer is a resounding and conclusive “No.” The numbers are completely clear and final, and anyone telling you otherwise is deeply mistaken. All counter-points fail for simple obvious reasons.

You can use ChatGPT as much as you like without worrying that you’re doing any harm to the planet. Worrying about your personal use of ChatGPT is wasted time that you could spend on the serious problems of climate change instead.

This post is not about the broader climate impacts of AI beyond chatbots1, or about whether AI is bad for other reasons (copyright, hallucinations, job loss, risks from advanced AI, etc.). I’m not especially “pro” or “anti” AI. I’m writing this because people who care about the climate and want to help the environment are getting distracted by a non-issue.

I’m not an authority on AI and energy use. I cite all my sources and claims and defer to what seems like the expert consensus where it exists. I’m a fan of linking citations with hypertext instead of footnotes, so my sources are all in the writing itself instead of at the bottom. I have a physics degree and taught physics for seven years, so I do know a lot about where and how energy is used.

We can divide concerns about ChatGPT’s environmental impact into two categories:

Personal use: How much ChatGPT increases your personal environmental footprint.

Global use: How much ChatGPT is harming the planet as a whole.

I’ll write a bunch of responses to the most common objections in each category.

Throughout this post I’ll assume the average ChatGPT query uses 0.3 Wh of energy, about the same as a Google search used in 2009. Here’s a summary of why 0.3 Wh is the most reasonable guess right now. It seems like image generators use ~1.22 Wh per prompt (with large error bars), so everything I say here also applies to AI images.

I’m collecting all my responses to critiques of this post here, and corrections here. If you think I’m leaving out any important climate costs of a prompt in this post, I’ve tried to cover what those costs could be here, and show that they don’t add much.

Contents

This post in a nutshell

Using chatbots emits the same tiny amounts of CO2 as other normal things we do online, and way less than most offline things we do. Even when you include “hidden costs” like training, the emissions from making hardware, energy used in cooling, and AI chips idling between prompts, the carbon cost of an average chatbot prompt adds up to less than 1/150,000th of the average American’s daily emissions. Water is similar. Everything we do uses a lot of water. Most electricity is generated using water, and most of the way AI “uses” water is actually just in generating its electricity. The average American’s daily water footprint is ~800,000 times as much as the full cost of an AI prompt. The actual amount of water used per prompt in data centers themselves is vanishingly small.

Because chatbot prompts use so little energy and water, if you’re sitting and reading the full responses they generate, it’s very likely that you’re using way less energy and water than you otherwise would in your daily life. It takes ~1000 prompts to raise your emissions by 1%. If you sat at your computer all day, sending and reading 1000 prompts in a row, you wouldn’t be doing more energy intensive things like driving, or using physical objects you own that wear out, need to be replaced, and cost emissions and water to make. Every second you spend walking outside wears out your sneakers just a little bit, to the point that they eventually need to be replaced. Sneakers cost water to make. My best guess is that every second of walking uses as much water in expectation as ~7 chatbot prompts. So sitting inside at your computer saves that water too. It seems like it’s near impossible to raise your personal emissions and water footprint at all using chatbots, because using all day on something that ends up causing 1% of your normal emissions is exactly like spending all day on an activity that costs only 1% of the money you normally spend.

There are no other situations, anywhere, where we worry about amounts of energy and water this small. I can’t find any other places where people have gotten worried about things they do that use such tiny amounts of energy. Chatbot energy and water use being a problem is a really bizarre meme that has taken hold, I think mostly because people are surprised that chatbots are being used by so many people that on net their total energy and water use is noticeable. Being “mindful” with your chatbot usage is kind of like filling a large pot of water to boil to make food, and before boiling it, taking a pipet and removing tiny drops of the water from the pot at a time to “only use the water you need” or stopping your shower a tenth of a second early for the sake of the climate. You do not need to be “mindful” with your chatbot usage for the same reason you don’t need to be “mindful” about those additional droplets of water you boil.

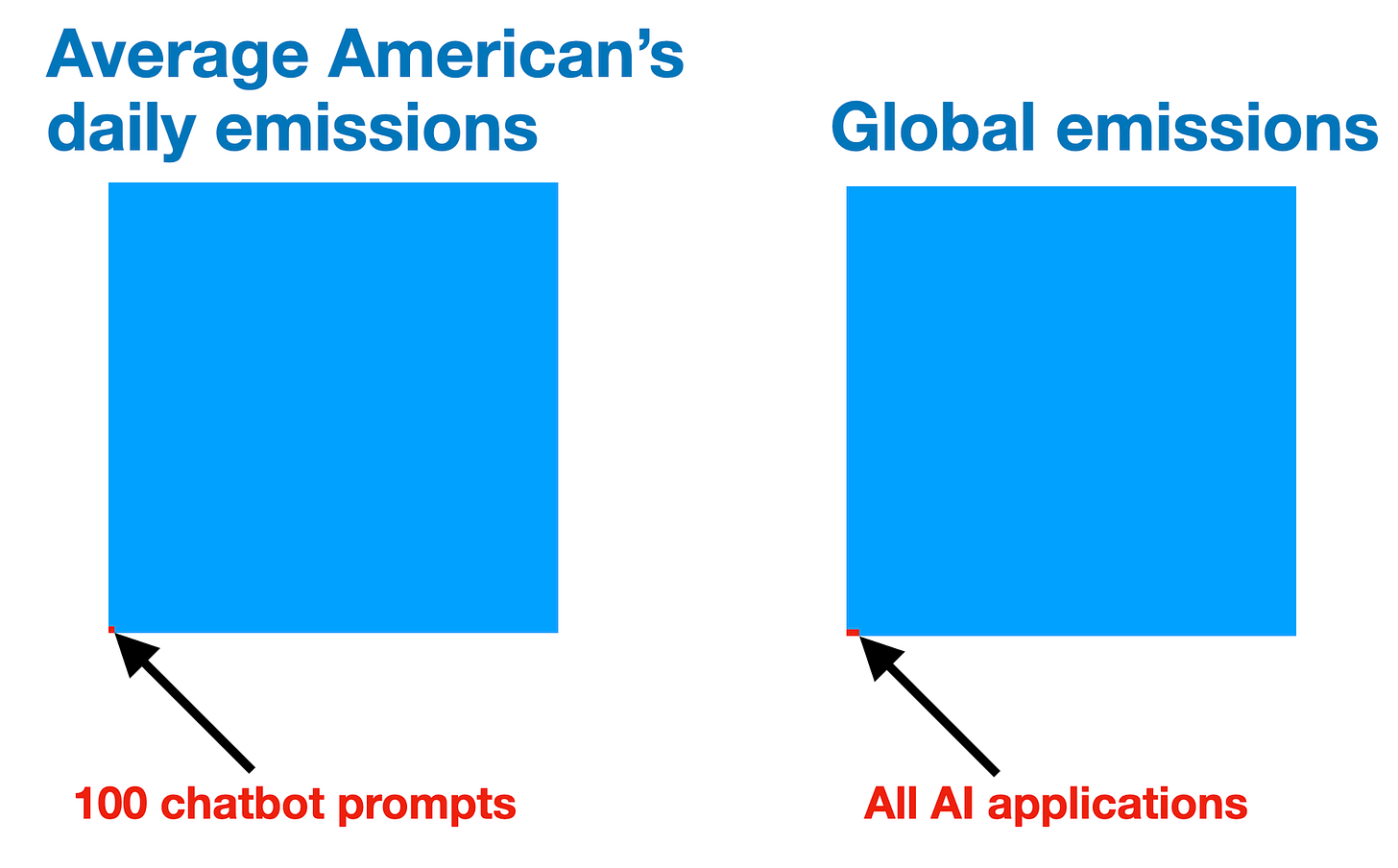

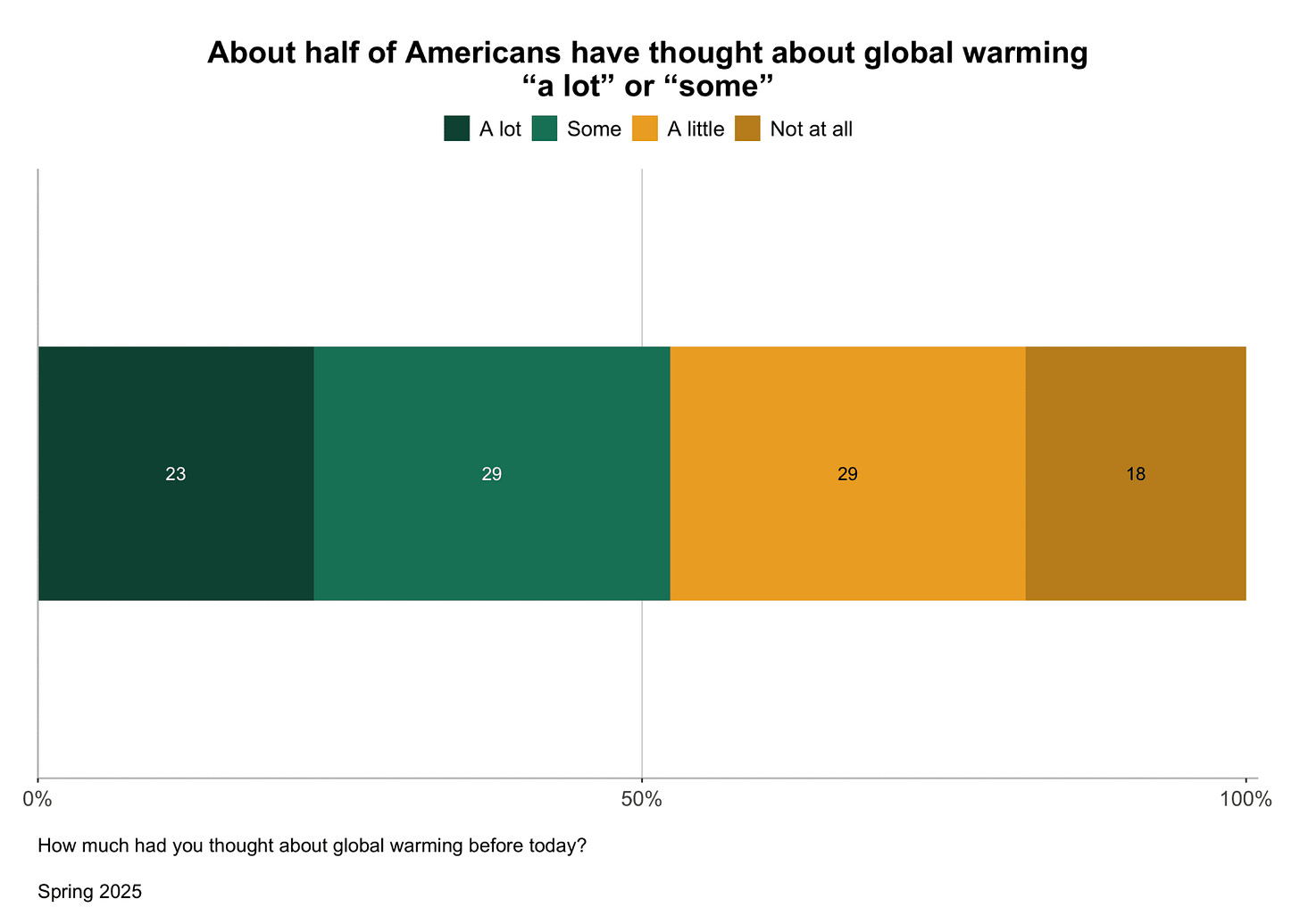

Some people think tiny parts of our emissions “add up” when a lot of people do them. They add up in an absolute sense, but they don’t add up to be a larger relative part of our overall emissions. If AI chatbots are just a 100,000th of your personal emissions, they are likely to be around a 100,000th of global emissions as well. We should mostly focus on systematic change over personal lifestyle changes, but if we do want to do personal lifestyle changes, we should prioritize cutting things that are actually significant parts of our personal emissions. That’s the only way we could reduce significant amounts of global emissions too.

The reason AI is rapidly using more energy is that AI is suddenly being used by more people, not that AI stands out as using a lot of energy per person using it. Personal chatbot usage is a tiny fraction of AI’s total energy energy and water footprint, it’s being used for way more. It’s like if the internet had been invented a second time and people were rapidly coming online.

The reason AI data centers use a lot of energy is that they are built to collect huge amounts of individually tiny computer tasks in a single physical place. This makes them more energy-efficient than other ways of doing the same things with computers. If we’re going to do things with computers, we should prefer that data centers manage a lot of it. Every time you interact with the internet, you’re using a data center in the same way you use any other computer. Globally, the average person uses the internet for 7 hours a day, but data centers only use 0.23% of the world’s energy. It’s a miracle of optimization that something we spend half our waking lives on can use less than a 200th of our energy. Computers in general have been ridiculously optimized to use as little energy as possible, so we should assume that the things we do on them will not be significant parts of our carbon footprints. It does not matter for the climate where emissions happen. If I’m right that individuals using chatbots are emitting way less than they would doing other things, then all the emissions caused by chatbots in data centers would have actually still happened, and there would have been a lot more of them, if people boycotted chatbots instead. So chatbots in data centers are often reducing emissions, they just concentrate the reduced emissions so we can see them all in one place. This makes them look bad, but they’re often preventing way more emissions that would just be more dispersed.

Data centers do put more strain on local grids than some other types of buildings, for the same reason a stadium puts more strain on a grid than a coffee shop: the stadium is serving way more people at once. Data centers are building-sized computers that tens of thousands of people are using at any one time. The reason they stand out is that they gather a large amount of aggregate energy demand into a tiny place, not that they’re using a lot of energy per user. In the equation (Total Energy) = (Energy per Prompt) x (Number of Prompts), energy per prompt is low, but the number of prompts in a data center is extremely high, so the total energy they use is high. This means that your personal use of AI is adding extremely tiny amounts of energy demand, and of all the things you can cut to reduce your emissions, it’s one of the very least promising. The fact that chatbots as a whole are using a lot of energy tells you nothing about whether you using it personally is wasteful, for the same reason that tens of billions of dollars are spent on candy bars globally, but you purchasing a candy bar isn’t financially wasteful. Deciding that you’re going to stop using AI for the sake of the climate is like going around your home and randomly unscrewing a single LED bulb, or pausing your microwave a few seconds early to save the planet. It’s so small that it’s a meaningless distraction.

The vast majority of AI’s effects on the environment will come from how it’s used, not from what happens in data centers. Amazon and Google Maps both have big impacts on the climate. Amazon might help or hurt a lot, and Google Maps optimizes a lot of car trips, but also might encourage more driving. But no one in debates about Amazon or Google’s climate impact says “The most important issue is the energy costs of running this website in data centers.” That would be crazy, because the websites are tools that cause people’s behavior to change, which leads to much larger changes in the physical world. If you’re concerned about AI’s impacts on the climate, the main question should be how using AI can help or hurt the climate, not the (tiny) costs of running AI in the first place.

Personal use

A ChatGPT prompt uses too much energy/water

Energy

A ChatGPT prompt uses 0.3 Watt-hours (Wh). This is enough energy to:

Leave a single incandescent light bulb on for 18 seconds.

Leave a wireless router on for 3 minutes.

Play a gaming console for 6 seconds.

Run a vacuum cleaner for 1 second.

Run a microwave for 1 second.

Run a toaster for 0.8 seconds.

Brew coffee for 10 seconds.

You can look up how much 0.3 Wh costs in your area. In DC where I live it’s $0.000051 (a two-hundredth of a cent). Think about how much your energy bill would have to increase before you noticed “Oh I’m using more energy. I should really try to reduce it for the sake of the climate.” What multiple of $0.000051 would that happen at? That can tell you roughly how many ChatGPT searches it’s okay for you to do.

If you were running ChatGPT’s servers in your home, to raise your energy bill by 1 dollar, you would need to send 19,600 prompts. One prompt every single second for 5 hours.

Emissions

Of course, in conversations about the climate, we don’t actually care directly about the energy. We care about the emissions. We need to be careful to include every possible way prompting ChatGPT can cause emissions. These are:

✅ The energy cost of an AI chip generating an answer to your prompt

✅ The energy of an idling AI chip between prompts

✅ The energy cost of cooling the AI chips

✅ Other energy overhead in the data center

✅ The fact that data centers use energy that’s 48% more carbon intensive than average

✅ The emissions from training the model in the first place (dividing emissions from training by the number of prompts the model receives)

✅ The embodied carbon of the AI chip (the emissions that were caused by making the hardware)

✅ The energy used to transmit the information from the data center to your device.

When you add all these, the full CO2 emissions caused by a ChatGPT prompt comes out to 0.28 g CO2. This is about 1/150,000th of the average American’s daily carbon emissions, or 0.0007%. For context, this is the same amount of CO2 emitted by:

Driving a sedan at a consistent speed for 4 feet

Using a laptop for 1 minute. If you’re reading this on a laptop and spend 20 minutes reading the full post, you will have used as much energy as 20 ChatGPT prompts. ChatGPT could write this blog post using less energy than you use to read it!

Because this is so low, encouraging people to stop using ChatGPT is basically never going to have any impact on their individual emissions. If individual emissions are what you’re worried about, ChatGPT is hopeless as a way of lowering them. It’s like seeing people who are spending too much money, and saying they should buy one fewer gum ball per month:

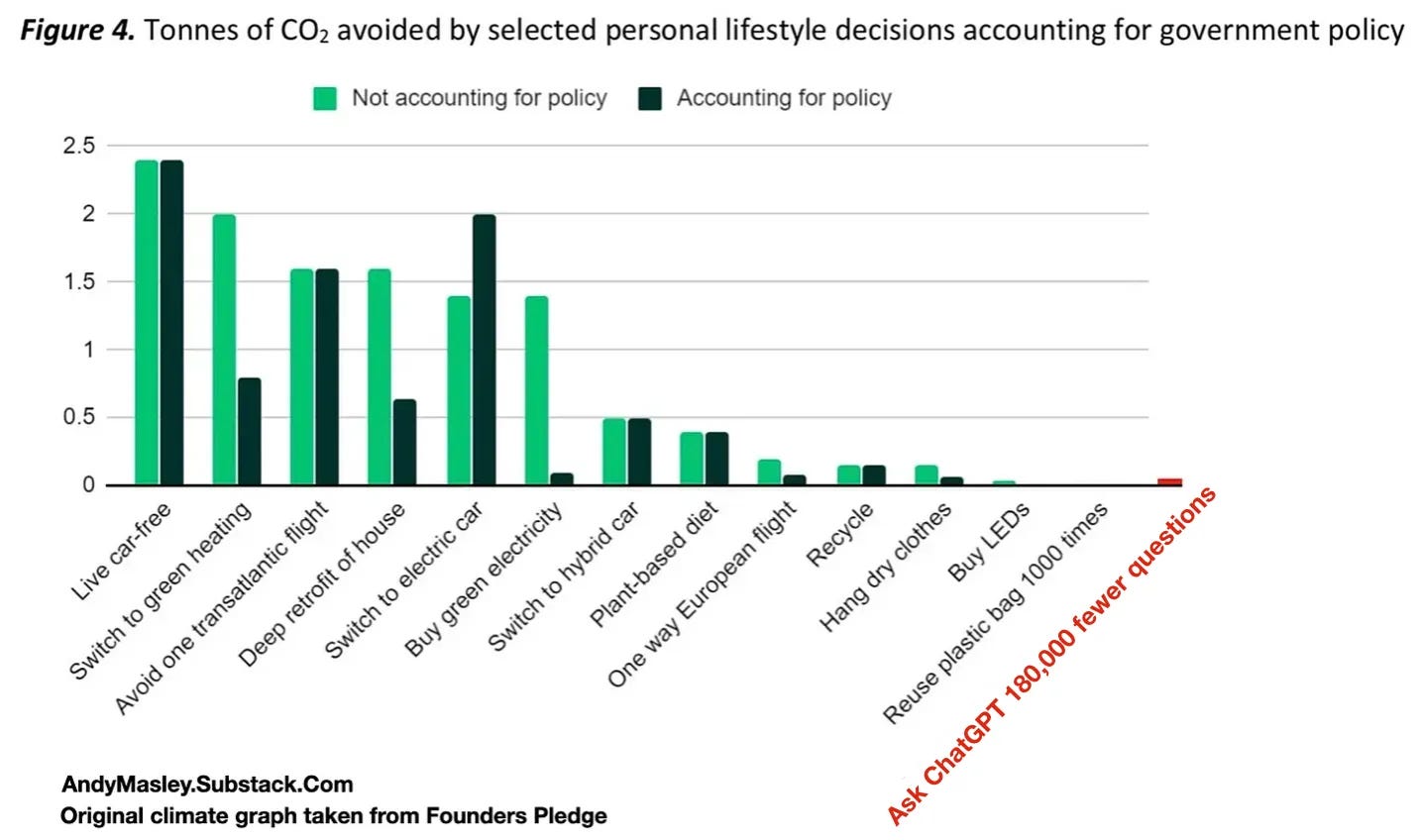

By being vegan, I have as much climate impact as not prompting ChatGPT 1,000,000 times each year (the water impact is even bigger). I don’t think I’m going to come close to prompting ChatGPT 1,000,000 times in my life, so each year I effectively stop more than a person’s entire lifetime of ChatGPT prompts with a single lifestyle change. If I choose not to take a flight to Europe, I save 10 million ChatGPT prompts. this is like stopping more than 100 people from searching ChatGPT for their entire lives. Preventing ChatGPT prompts is a hopelessly useless lever for the climate movement to try to pull. We have so many tools at our disposal to make the climate better. Why make everyone feel guilt over something that won’t have any impact?

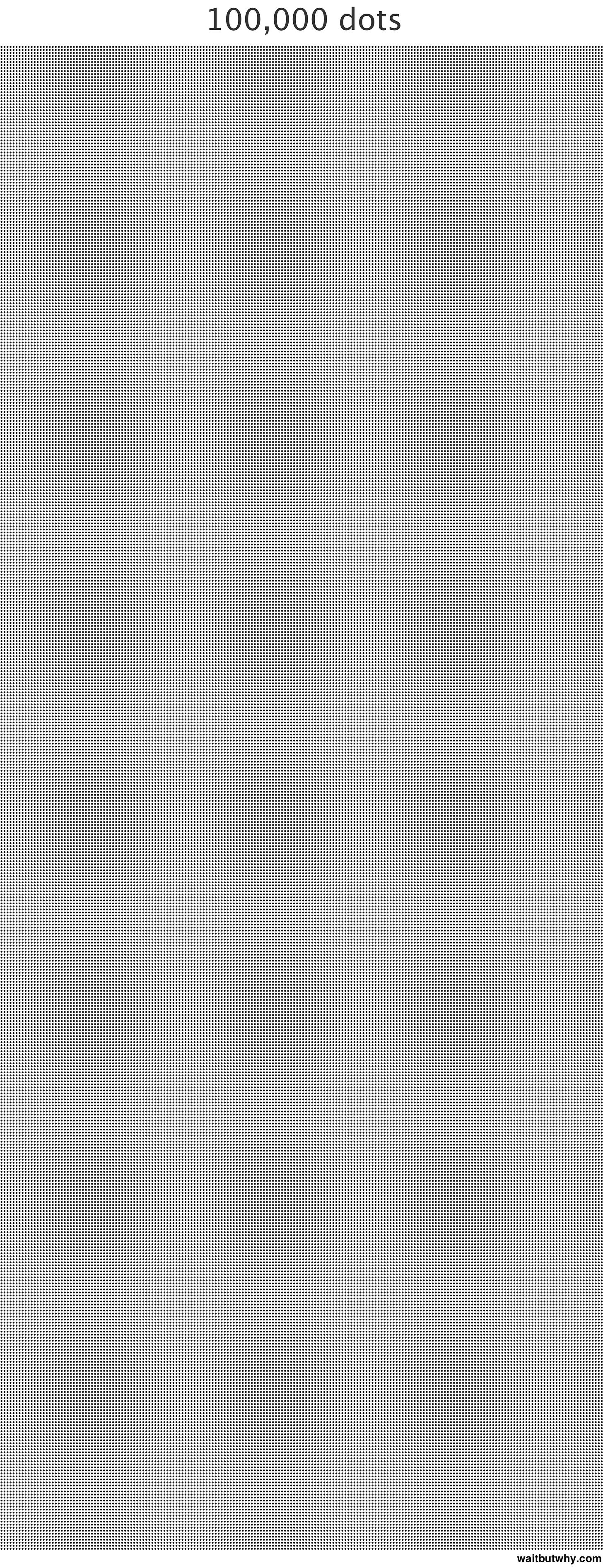

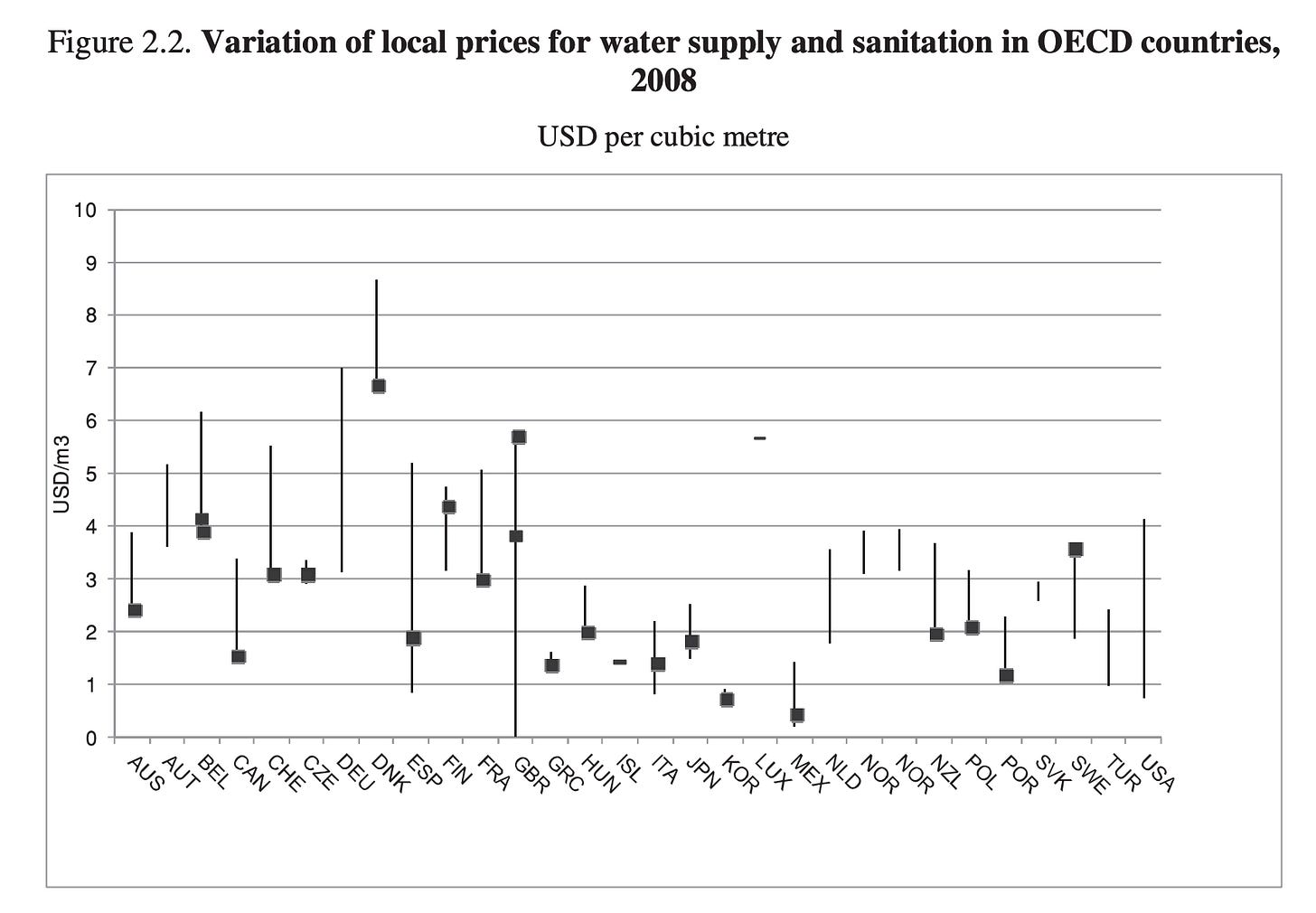

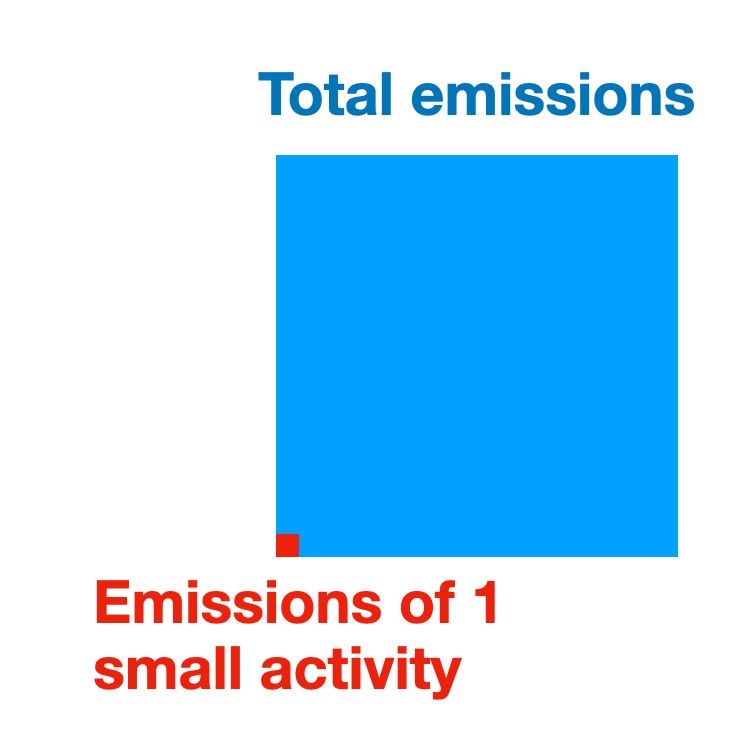

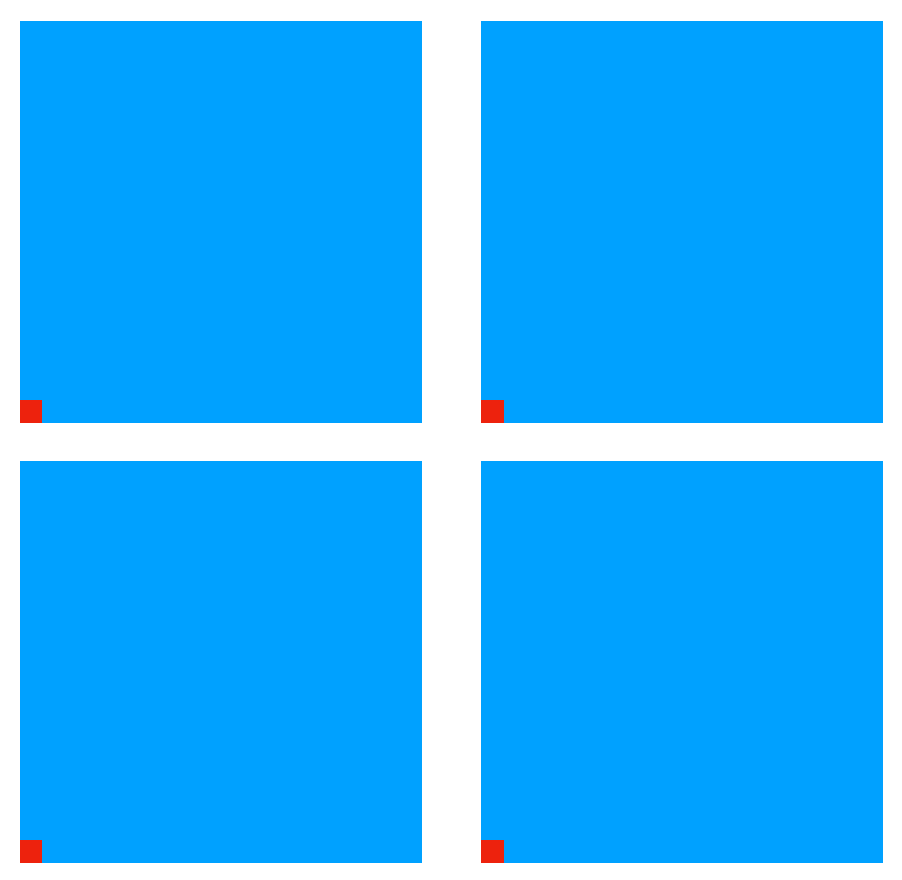

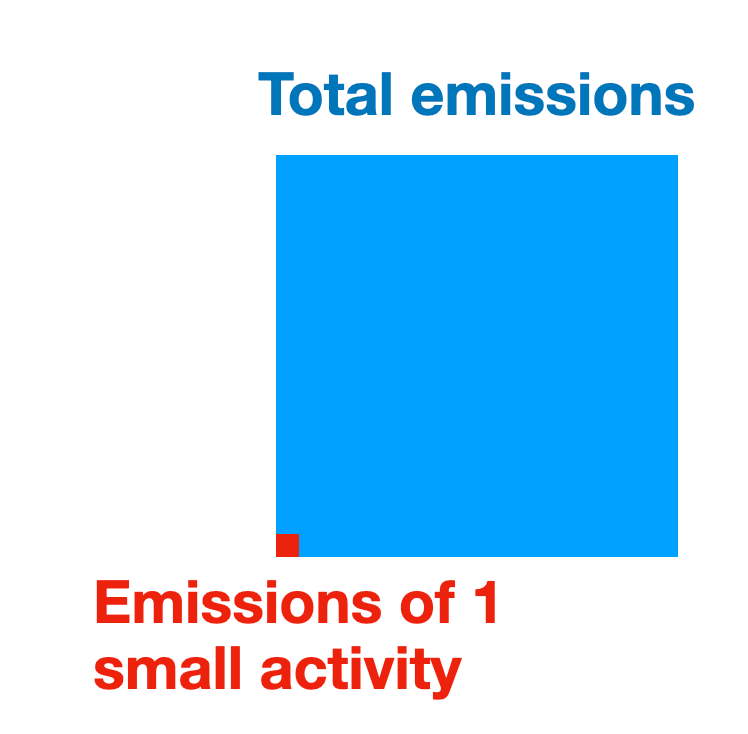

The average American emits about 100,000 times as much CO2 each day. If each of these dots is one ChatGPT prompt, all the dots together are how much you emit in one day.

I still find, even after showing this, that some people think using literally any additional energy is bad, because “every bit matters.” The thing is that our energy use changes a lot day to day, just like the money we spend changes day to day. If I started spending an additional penny per month, I wouldn’t notice, because there would be other days where I’d randomly spend way more or fewer pennies on other things. If I looked at a graph of my spending, the penny would be drowned out in the random noise of my other decisions. ChatGPT prompts are like this. They use so little energy that they get drowned out in the random ways we change our energy use day to day. If you looked at a graph of my energy footprint before and after using ChatGPT, you wouldn’t notice any change at all.

We have limited hours in the day, and different choices for how we spend our time. If prompting ChatGPT 100 times and reading its responses takes up hours of my time that I could have spent playing a video game or watching Netflix or driving my car, then using it actually prevents me from emitting way more, because those other things use way more energy per hour. Printing a physical book uses 5,000 Wh, so even just sitting down and reading a book you bought for 6 hours (using 833 Wh per hour) is going to use more energy per minute than ChatGPT, unless you prompt ChatGPT 1000 times per hour, or once every 3 seconds for a full hour. Switching to using ChatGPT from another activity is almost always going to decrease the total energy I use every day. This isn’t an argument that you should only use ChatGPT! It’s often worth it to spend more energy. But people sitting and using ChatGPT are often using way less energy per minute than almost anyone else in the world.

Water

I think a lot of people don’t realize how much water we each use every day. Altogether, the average person’s daily water footprint is 422 gallons, or 1600 liters. Our best current data on AI prompts’ water use from a thorough study by Google, which says that each prompt might only use ~2 mL of water if you include the water used in the data center as well as the offsite water used to generate the electricity.

This means that every single day, the average American uses enough water for 800,000 chatbot prompts. Each dot in this image represents one prompt’s worth of water. All the dots together represent how much water you use in one day in your everyday life (you’ll have to really zoom in to see them, each of those rectangles is 10,000 dots):

However, that 2 mL of water is mostly the water used in the normal power plants the data center draws from. The prompt itself only uses about 0.3 mL, so if you’re mainly worried about the water data centers use per prompt, you use about 300,000 times as much every day in your normal life. That’s the same water your local power plant uses to generate a watt-hour of energy, enough to use your laptop for about 2 minutes. So every hour that you use your laptop, you’re using up 30 chatbot prompt’s worth of water in a nearby power plant.

Have you ever worried about how much water things you did online used before AI? Probably not, because data centers use barely any water compared to most other things we do. Even manufacturing most regular objects requires lots of water. Here’s a list of common objects you might own, and how many chatbot prompt’s worth of water they used to make (all from this list, and using the onsite + offsite water value):

Leather Shoes - 4,000,000 prompts’ worth of water

Smartphone - 6,400,000 prompts

Jeans - 5,400,000 prompts

T-shirt - 1,300,000 prompts

A single piece of paper - 2550 prompts

A 400 page book - 1,000,000 prompts

If you want to send 2500 ChatGPT prompts and feel bad about it, you can simply not buy a single additional piece of paper. If you want to save a lifetime supply’s worth of chatbot prompts, just don’t buy a single additional pair of jeans.

Because generating electricity in America often involves water, anything that you do that uses electricity often also uses water. The average water used per kWh of electricity in America is 4.35 L/kWh, according to the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory. This has a few weird assumptions (explained here), so to be conservative I’ll divide it in half to 2 L/kWh. This means that every kWh of electricity you use evaporates the same amount of water as 1000 chatbot prompts (including both onsite + offsite water cost). Conveniently, 1 prompt’s water per Watt-hour.

Here are some common ways you might use electricity, and how many AI prompts’ worth of water the electricity used took to generate:

Playing a PS5 for an hour - 200 prompts’ worth of water

Using a laptop for an hour - 50 prompts’ worth of water

An LED light bulb on for an hour - 6 prompts

A digital clock for an hour - 1 prompt

Heating a kettle of water - 125 prompts’ worth of water (the kettle itself has enough water for ~500 prompts)

Heating a bath of warm water - 5000 prompts (the bathtub itself has enough water for 80,000 prompts)

Even just going for a walk outside slightly wears out your sneakers. Typical athletic sneakers often last for 300-500 miles, and take 4 million ChatGPT prompts’ worth of water to make. This means that every mile you get out of your sneakers uses 8000 ChatGPT prompts’ worth of water. Every single second you spend walking in sneakers uses enough water for 7 prompts. At the end of an hour walk, you would have used enough water for 24,000 prompts.

If you want to reduce your water footprint, avoiding AI will never make a dent. These numbers are so incredibly small it’s hard to find things to compare them to. If you send 10,000 chatbot prompts per year, the water used in AI data centers themselves adds up to 1/300,000th of your total water footprint. If your water footprint were a mile, 10,000 chatbot prompts would be 0.2 inches.

Even if AI is completely useless, and all the water you use on it is “wasted,” literally everything else you do in life involves larger amounts of wasted water, even if that activity is really valuable for you. If you boil water to make healthy food, you could make the exact same amount of food if you took a water dropper and extracted a few milliliters from the pot. A medium-sized pot can hold ~10 liters of water. That’s enough for 5000 chatbot prompts. If you took a dropper and removed 1/5000th of the water from the pot, you would still be able to use it to make whatever food you want, so that extra amount is “wasted” but it’s so small that it doesn’t matter at all. If you saw someone filling a pot like this:

and then using this dropper to remove tiny amounts of water at a time to “save” as much water as they could until the pot only contained exactly as much water as they needed so that they didn’t waste a drop,

you would correctly say that was a huge waste of time. In no other places do we think it’s reasonable to worry about “wasting” such a tiny amount of water in our personal lives. Even if you think all water used on AI is completely wasted, it still shouldn’t bother you any more than the fact that people don’t spend the time to remove tiny drops of water from the pots they boil to make food.

ChatGPT is bad relative to other things we do (it’s ten times as bad as a Google search)

If you multiply an extremely small value by 10, it can still be so small that it shouldn’t factor into your decisions.

If you were being billed $0.0005 per month for energy for an activity, and then suddenly it began to cost $0.005 per month, how much would that change your plans?

A digital clock uses one million times more power (1W) than an analog watch (1µW). “Using a digital clock instead of a watch is one million times as harmful to the climate” is correct, but misleading. The energy digital clocks use rounds to zero compared to travel, food, and heat and air conditioning. Climate guilt about digital clocks would be misplaced.

The relationship between Google and ChatGPT is similar to watches and clocks. One uses more energy than the other, but both round to zero.

When was the last time you heard a climate scientist say we should avoid using Google for the environment? This would sound strange. It would sound strange if I said “Ugh, my friend did over 100 Google searches today. She clearly doesn’t care about the climate.” Google doesn’t add to our energy budget at all. Assuming a Google search uses 0.03 Wh, it would take 300,000 Google searches to increase your monthly energy use by 1%. It would be a sad meaningless distraction for people who care about the climate to freak out about how often they use Google search. Imagine what your reaction would be to someone telling you they did ten Google searches. You should have the same reaction to someone telling you they prompted ChatGPT.

What matters for your individual carbon budget is total emissions. Increasing the emissions of a specific activity by 10 times is only bad if that meaningfully contributes to your total emissions. If the original value is extremely small, this doesn’t matter.

It’s as if you were trying to save money and had a few options for where to cut:

You buy a gum ball once a month for $0.01. Suddenly their price jumps to $0.10 per gum ball.

You have a fancy meal out for $50 once a week to keep up with a friend. The restaurant host likes you because you come so often, so she lowers the price to $40.

It’s very unlikely that spending an additional $0.10 per month is ever going to matter for your budget. Spending any mental energy on the gum ball is going to be a waste of time for your budget, even though its cost was multiplied by 10. The meal out is making a sizable dent in your budget. Even though it decreased in cost, cutting that meal and finding something different to do with your friend is important if you’re trying to save money. What matters is the total money spent and the value you got for it, not how much individual activities increased or decreased relative to some other arbitrary point.

Google and ChatGPT are like the gum ball. If a friend were worried about their finances, but spent any time talking about foregoing a gum ball each month, you would correctly say they had been distracted by a cost that rounds to zero. You should say the same to friends worried about ChatGPT. They should be able to enjoy something that’s very close to free. What matters for the climate is the total energy we use, just like what matters for our budget is how much we spend in total. The climate doesn’t react to hyper specific categories of activities, like search or AI prompts.

If you’re an average American, each ChatGPT prompt increases your daily energy use (not including the energy you use in your car) by 0.001%. It takes about 1,000 ChatGPT prompts to increase your daily energy use by 1%. If you did 1,000 ChatGPT prompts in 1 day and feel bad about the increased energy, you could remove an equal amount of energy from your daily use by:

Running a clothes drier for 6 fewer minutes.

Running an air conditioner for 18 fewer minutes.

ChatGPT uses enough energy that you should be very careful with how you use it. Don’t use it as a search engine or a calculator or just to goof around

There are costs that are just so incredibly small that it does not matter if you take a few more. Imagine that someone told you that they had perfectly timed their microwave down to the second for each meal. They knew that their vegan chicken nuggies needed exactly 3 minutes and 42 seconds. Any longer and they would be wasting energy. That would be admirable, but a very tiny thing that would take a lot of extra effort relative to how much it helps the climate (basically not at all). If someone else just set the microwave to 4 minutes, this would use so little extra energy that it wouldn’t be bad for the climate at all.

This would also be 20 ChatGPT search’s worth of extra energy.

I sometimes hear people say that you should “think carefully about your ChatGPT use” and “be environmentally aware while using it” because of its environmental impact, and not just use it for simple things you could use other services for, like a simple search or a calculator or just making jokes. This sounds a lot like scolding the person setting their microwave to 4 minutes instead of 3:42. It’s misunderstanding just how little energy is involved.

I regularly use the Google search bar as a calculator. I’m too lazy to click on the calculator app on my computer. The search bar is right there. This adds a tiny tiny bit of energy cost, but it’s not enough that I should ever worry.

Suppose you gave yourself an energy budget for goofy ChatGPT prompts. Every year, you’re allowed to use it for 1,000 goofy things (a calculator, making funny text, a simple search you could have used Google for). At the end, all those prompts together would have used the same amount of energy as running a single clothes dryer a single time for three minutes. This would increase your energy budget by 0.003%. This is not enough to worry about. If you feel like it, please goof around on ChatGPT.

There are other hidden costs that you’re not including here

There are a ton of different ways we could add to the cost of a ChatGPT prompt by considering things like how much it “normalizes” using AI, or how much it encourages the data center buildout overall. Because this is such a long deep dive, I’ve written it as a separate post that you can read here.

What about super long prompts and responses, like deep research?

The energy an AI prompt uses is largely dependent on the time it takes to generate its output. You can choose to give a chatbot longer to “think” about its response, which produces higher quality answers. At the extreme end, you can do a “deep research” prompt to have it go super in-depth and write a long thorough article with citations. Is doing this bad for the environment?

We don’t have clear numbers for how much deep research prompts use. The numbers I give here will just be a guess. It’s the best I can offer for now and you can decide if it’s reasonable. Once more clear data comes out I’d be happy to circle back.

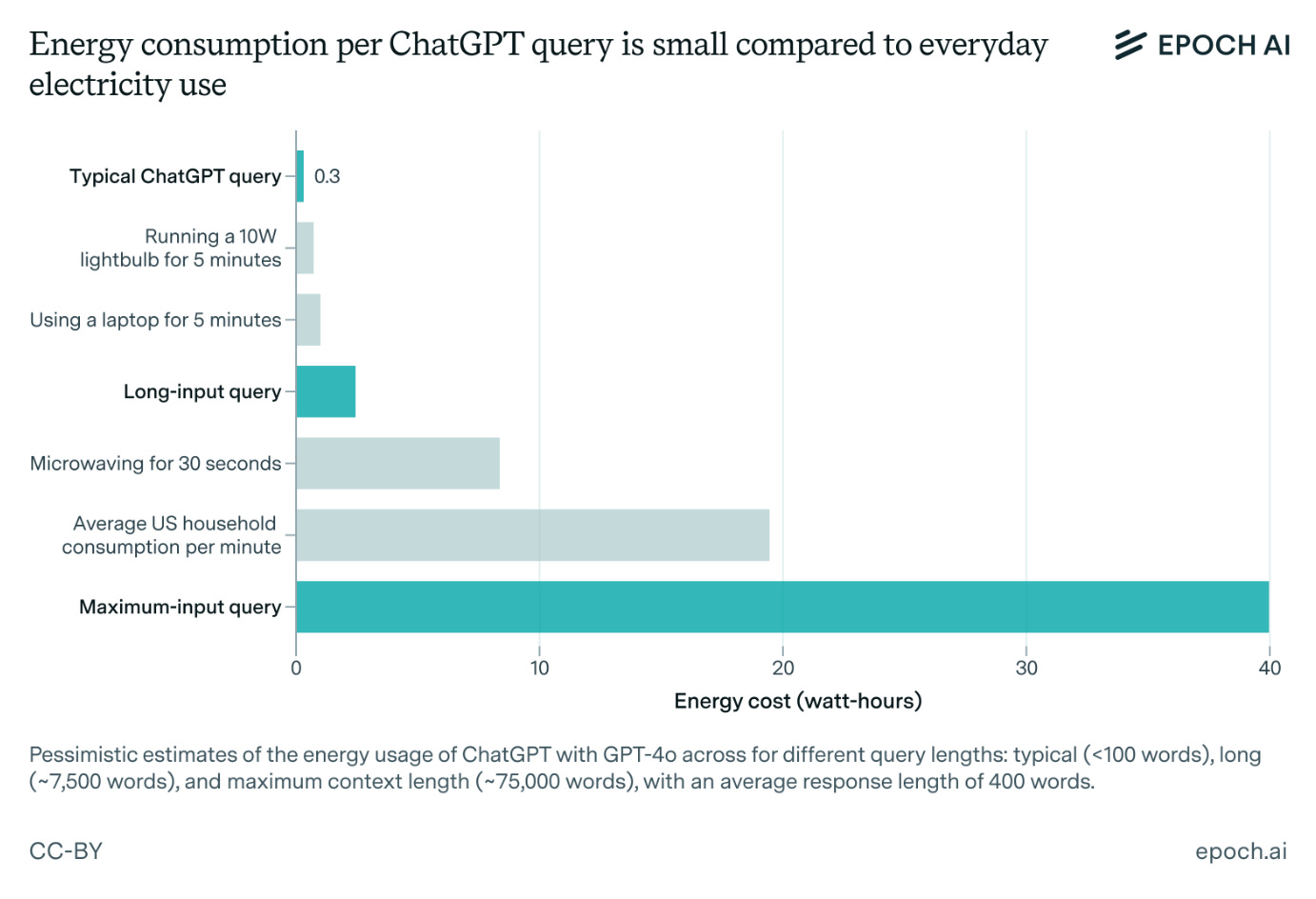

Back in January, EpochAI took a guess at the maximum amount of energy a chatbot could spend given the longest possible prompt we could give it (75,000) words. The found it would use around 40 Wh. About 133x as much energy as the average prompt.

In my experience, most deep research and long reasoning prompts take a few minutes to resolve, landing them at around 100x the time it takes for a normal prompt. Maybe a reasonable guess is that they use 100x as much energy. I’ll stick to 30 Wh as my best guess for what a deep research prompt uses. This has wide error bars.

30 Wh is about 0.1% of an average American’s total household electricity use throughout the day. If you do 10 deep research prompts throughout the day, you increase your total electricity use by 1%. It’s equivalent to running a microwave for ~2 minutes and 30 seconds. Let’s say the emissions of a normal prompt are also multiplied by 100. This would mean a deep research prompt emits 28 g CO2, which adds 0.07% to your daily carbon emissions. To raise your emissions by 1%, you would need to do 14 deep research prompts per day.

But doing 14 deep research prompts every single day seems unreasonable, because deep research responses are long. At the average American’s reading speeds, this deep research prompt I asked for would take half an hour to read. If you did 14 deep research prompts in a day, you would spend your entire workday doing nothing but reading deep research prompts. If we measure deep research prompts by the energy used divided by the time it takes to read the results, they’re pretty comparable to normal AI prompts. This deep research prompt might’ve taken 100 times the energy, but also probably takes 30x as long to read, meaning it’s really only 3x as energy-intensive as a normal prompt if we measure by total text generated.

It seems like the only way you would do 14 deep research prompts in 1 day is if you either

Were spending the whole day reading long text generated by AI, in which case you’re probably using way less energy than normal, because you’re just sitting in one place.

Were actively trying to max out the energy you use with AI by running a ton of deep research prompts that you wouldn’t actually read. With some work this could get your daily emissions up by a few percentage points. But if you were just sitting around trying to increase your daily emissions as much as possible, it’s way better that you’re using AI to do it compared to any other option. It’d be much easier to just get into your car and drive in circles for a while. So even in this situation, AI seems better for the environment compared to most other options you have available.

I would also put forward that the results of deep research prompts are often ridiculously valuable. I think their value is less debatable than normal chatbot use. I’d very strongly encourage you to try out deep research for yourself on a subject you’re trying to learn about. Basically, I see deep research as the production of a very thorough overview with citations of any topic I’m trying to learn about, and that I can’t find a similar summary of online in one place. Here’s an example deep research result I got on chatbot energy usage. The question of deep research for me is “Is it acceptable to produce a report of this quality using the energy I use to microwave a bowl of popcorn?” Of all the ways I could use energy, deep research prompts basically always feel worth the investment. If I had a physical machine in my home that used as much energy as my microwave, and each time I ran it it produced a deep research-quality report on something I was trying to learn about, I wouldn’t consider that wasteful.

Global use

Data centers use too much energy

This point requires a lot of details on what data centers are, how they work, and how they manage AI prompts. It will be the longest section here.

The reasons why data centers are using a lot of energy in the places they are built are that:

AI as a whole is being used a lot.

Data centers concentrate huge amounts of individually very tiny computer tasks in one place. Concentrating these tasks makes data centers way more energy-efficient. For AI data centers, in the equation

total energy = (energy per prompt) x (number of prompts)

the energy per prompt is very small, but the number of prompts is extremely large. Data centers manage AI responses from people all over the world, concentrated in individual buildings.

Data centers put very concentrated demand on local grids without increasing global emissions much, but the reason it’s concentrated is to make the data center maximally energy-efficient. This very concentrated demand sometimes incentivizes more carbon-intensive energy sources.

We’ll explore each in a lot of detail in this section. If you want, you can skip to the summary here.

The reason AI’s energy costs are rising so much is that it’s being used so much, not that each prompt uses a lot of energy

AI's energy use has exploded because AI usage has exploded.

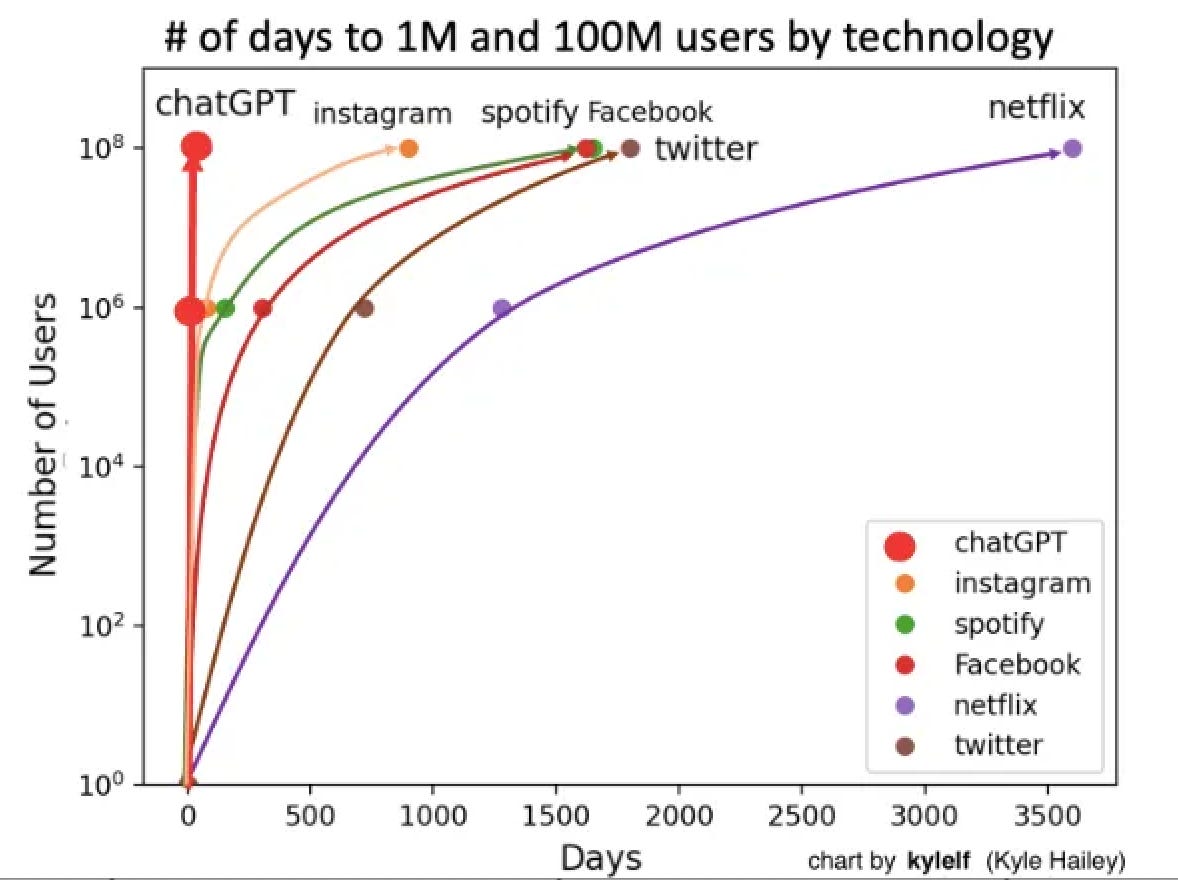

ChatGPT grew faster than any previous major app.

It’s now the 5th most popular website with 5.7 billion monthly visits, beating out Wikipedia, Reddit, and Amazon. It’s processing 2.5 billion daily prompts. 51% of professional developers surveyed by Stack Overflow use AI daily, and only 15% report that they don’t use it or plan to. 20-30% of code at Microsoft is now AI-written. AI is also embedded into many ways we use the internet, the clearest example being Google search’s AI summary.

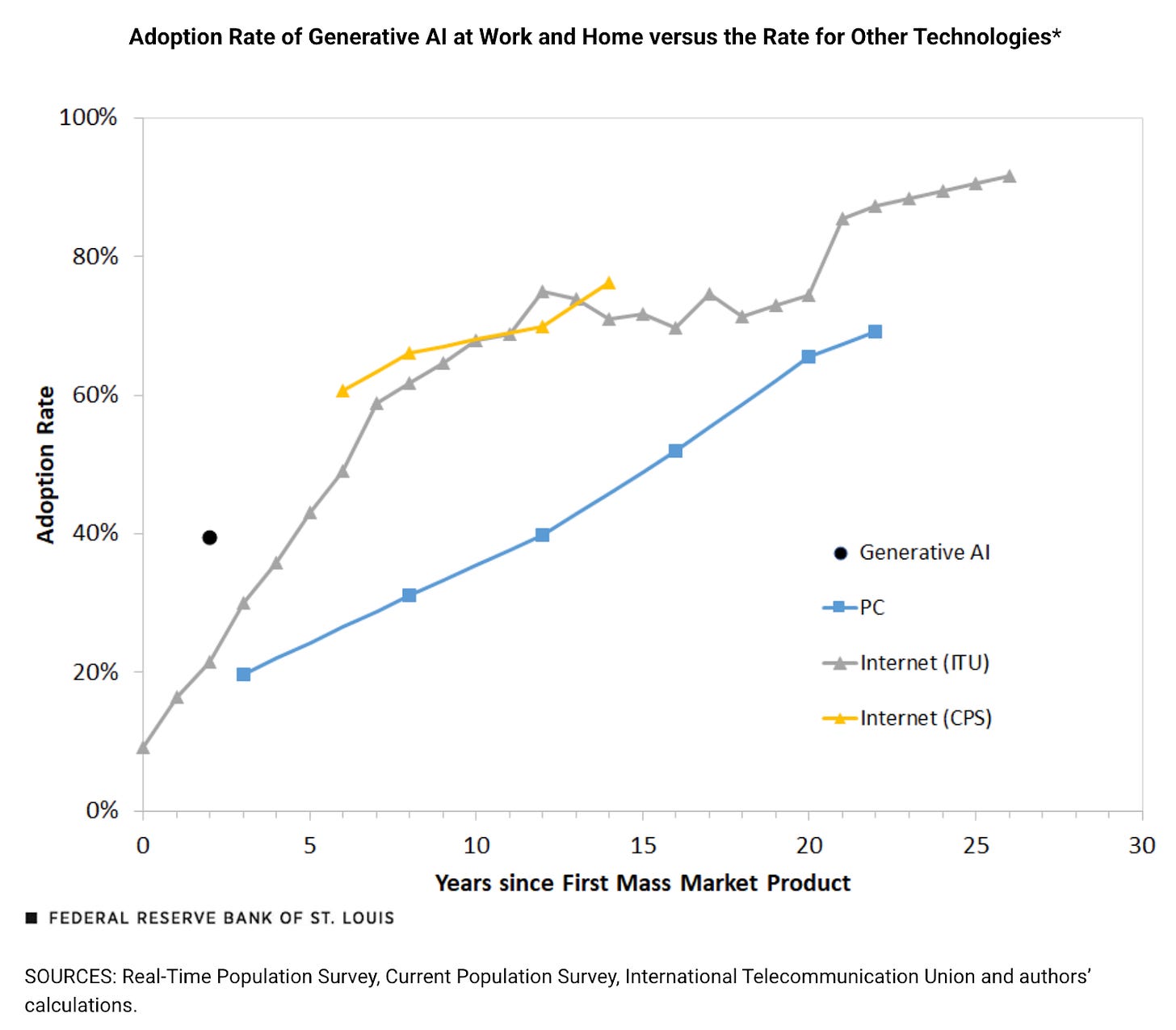

Generative AI may be the fastest-adopted technology ever.

Critics point out that this doesn't account for the intensity of use (which is lower than this graph would suggest) but AI is still ranks among the most rapidly adopted technologies.

In the equation Total energy = (Number of prompts) x (energy per prompt), the energy per prompt is low, but the number of prompts is so high that the total energy is high too. Next, we’ll see why data centers put so much strain on local grids, even though globally they use very little energy relative to how much we interact with them.

What is a data center?

A data center is a facility that stores a large number of computers, and infrastructure for power, cooling, and networking them. It’s effectively a building-sized computer. Data centers run most things you do online. Websites, cloud storage, email, and video streaming are all hosted and stored in data centers. You are interacting with data centers most of the time you’re online.

AI models are trained and run in data centers. When people talk about the environmental effects of AI, they are often talking about AI activity in data centers.

Data centers use lots of energy for massive amounts of computing. Similar to fans in personal computers, data centers require cooling systems to deal with the heat generated when they run. The most energy-efficient way to cool them is often running cool water near the servers to absorb the heat. The warmed water is then either evaporated, or cooled down and circulated again.

Learn more about data centers here.

The central environmental paradox of data centers

The environmental paradox of data centers is that they put so much strain on the surrounding energy grid because, not despite the fact that they have been made so uniquely energy-efficient. This is due to the economies of scale that come with running so many servers in one building.

Data centers are very efficient

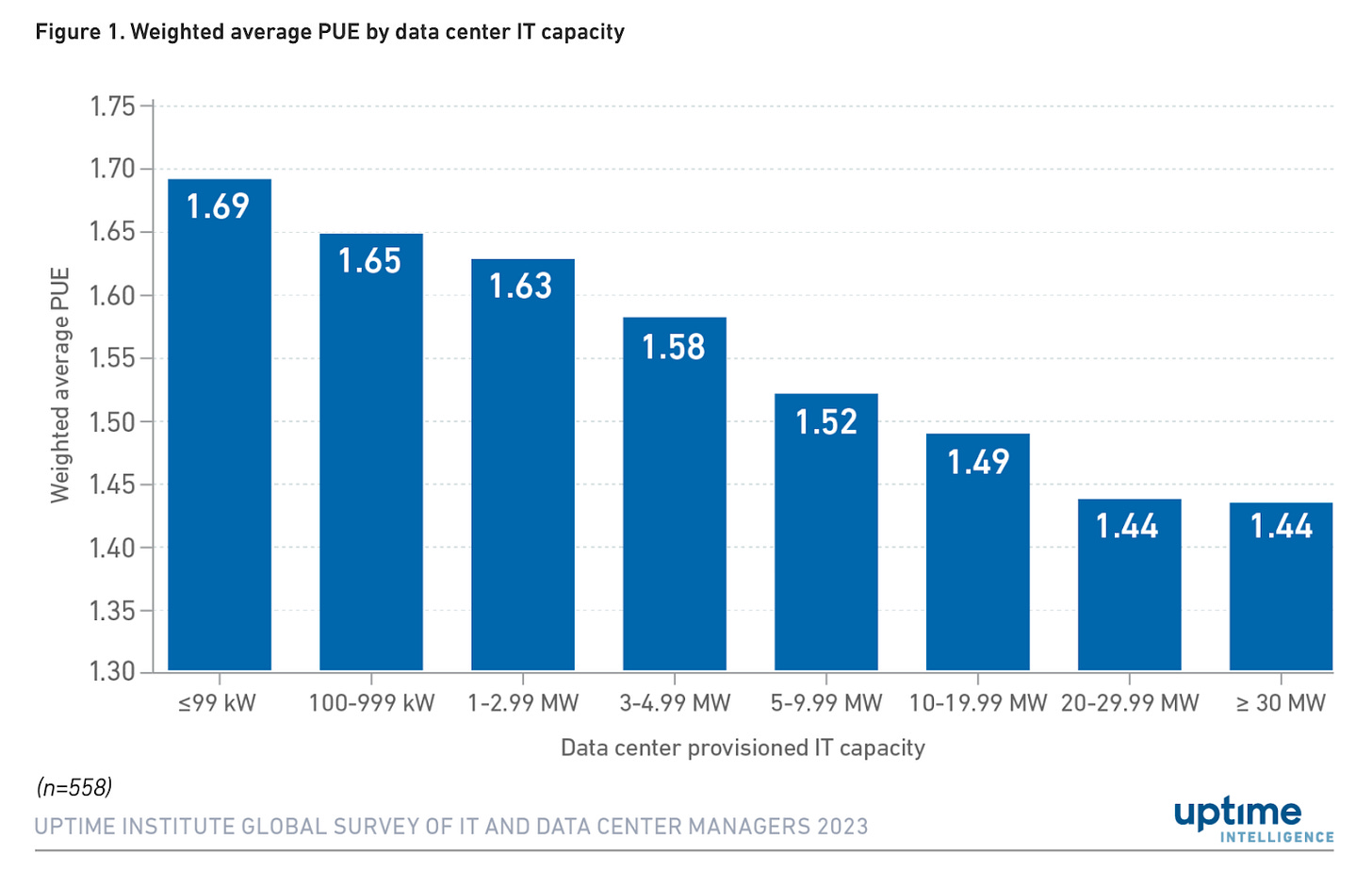

Power Usage Effectiveness (PUE) measures data center efficiency: total energy input divided by energy delivered to servers.

PUE = Energy data center takes inEnergy data center delivers to servers

A perfectly efficient data center would have a PUE of 1. The energy coming in would perfectly equal the energy used by the chips. No data center can actually achieve a PUE of 1, due to lighting, air conditioning, and heat loss.

PUE does not measure water use, or the carbon intensity of the electricity. Data centers use a separate WUE measure for water.

In practice, hyperscale data centers often achieve ~1.1. The industry average is ~1.56.

For context, power lines typically lose ~5% of energy during transmission, meaning they have an energy input-to-output ratio of 1.05. Google has achieved PUE below 1.05 at some of their data centers. This means Google has optimized their data center operations so efficiently that they waste less energy on non-computing infrastructure (cooling, lighting, etc.) than the average power line loses just moving electricity from point A to point B. In other words, their data centers are more energy-efficient at delivering power specifically to computing chips than the electrical grid is at simply transmitting power.

Many hyperscaler data centers are achieving very low PUEs because they are optimized at every level of design and operation. Because the companies using them are also running them, they have a financial incentive to optimize the data center’s energy use.

Larger data centers benefit from economies of scale: shorter transmission distances, reduced losses, and optimization opportunities unavailable to smaller facilities. There are other benefits to clustering AI chips together as well, but the energy benefits alone are significant. Larger data centers operate more efficiently.

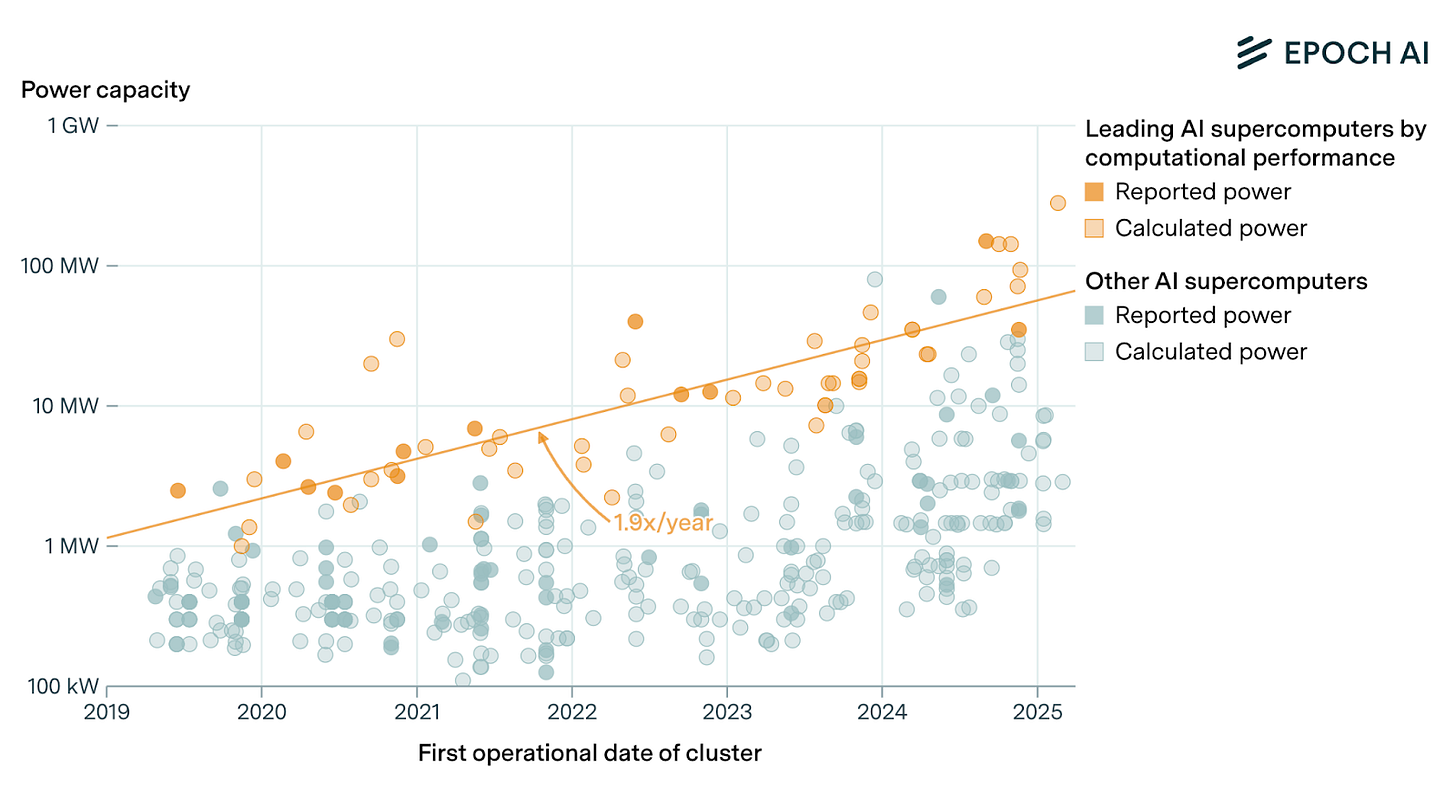

Data center power demand can get very large. For context, 30 MW of power (on the far right of the graph) is enough to power a town of about 60,000 people. xAI’s Colossus is the largest AI supercomputer, with a maximum power capacity of 280 MW, the same as a city with half a million people.

Because larger data centers are more energy-efficient, if you want your AI prompt to use as little energy as possible, you should (all else equal) prefer it to be processed in a very large data center.

In general, data centers are the most energy-efficient way to do the large-scale computing that services like the internet and AI require. Companies already have financial incentive to make them efficient. If we hold the amount of computations equal, Data centers are the most energy-efficient method for large-scale computing.

Data center energy and water demands are high relative to most commercial buildings

Data centers have some of the most concentrated energy demands of any type of building. They also require constant reliable power. Their computers run 24/7, and because a single large data center is handling computing for so many people, even a brief power outage can be uniquely bad for the business. Data centers aspire to “five 9’s of reliability”: the center should function normally for 99.999% of the time. As a result, they strain local grid capacity.

This strain can lead to greater reliance on fossil fuels. This occurs through the concept of marginal emissions. When electricity demand rises, utilities must activate additional power sources. The "marginal" source (the next plant brought online) is often a fossil fuel "peaker plant" (a power plant called upon during times of high electricity demand to supply power to the grid, often using natural gas turbines that can start up quickly). These plants are designed to ramp up quickly but are often less efficient and more polluting per unit energy than the average grid mix.

A data center's constant, high demand reduces the grid's flexibility and increases the baseline load, making it more likely that these high-polluting marginal sources are used. Furthermore, the rapid growth of data center demand is outpacing the deployment of new renewable energy and transmission infrastructure. This has led utilities in several states, including Georgia, Kansas, and Virginia, to delay the retirement of older fossil fuel plants or propose new natural gas plants to ensure grid reliability.

So when a large new constant load like a data center is added, it can increase the amount of fossil generation needed at the margin, making the power they consume more carbon-intensive than the grid average. Data centers also maintain backup generators (often diesel) in case of outages.

The paradox

To recap:

Data centers are so uniquely energy-efficient, and become more efficient the more computing they manage (due to economies of scale), that companies are incentivized to do gigantic amounts of computing in them, and keep them running 24/7. All else equal, if you want an AI tool to use the least energy possible, you should prefer it to be run in the biggest data center possible.

Because they concentrate so much computing inside, and need constant reliable power, even though each computation is energy-efficient, overall data centers have the highest concentrations of energy demand of basically any commercial buildings.

Local energy and water grids were not designed with these hyper-concentrated, very constant demands in mind, so data centers can sometimes strain the capacity of local grids. This sometimes increases fossil fuel dependance, because they can provide more consistent backup power compared to renewables.

This demand puts a strain on the surrounding grid and sometimes favors the use of fossil fuels, even though (and actually because) what’s happening in the data center itself is so uniquely energy-efficient.

The central paradox: data centers strain local grids precisely because they've been made so efficient.

Failing to understand this can lead to bad ideas for how to solve the growing problem of AI emissions. While it may be possible to make small improvements in data center efficiency, it’s unlikely that this would reduce emissions nearly as much as making the grid around data centers greener or enforcing stricter environmental regulations around how the data center generates back-up energy.

What should we expect to see based on the paradox of data centers?

Locally, we should expect data centers to have much higher rates of energy and water use than basically any other commercial or industrial buildings, and to put some strain on local grids as a result.

Globally, data centers should be a small part of energy and water use (and emissions), because they’re uniquely efficient with the resources they use.

The data confirms this.

What would we expect to see globally if data centers are so hyper-efficient?

What would we expect to see if data centers are so hyper-efficient? They should be a tiny, tiny part of our emissions relative to how much we use them, but concentrate that efficient energy usage in specific places and strain local grids. I think of this as the environmental paradox of data centers: they both put uniquely large concentrated demand on local grids, but are also tiny efficient parts of the global energy grid. This creates confusion in discussing their environmental impacts.

Globally, the average person interacts with the internet for 7 hours per day. The entire time they’re interacting with the internet, they’re effectively using a data center as they would a personal computer. Data centers host and organize and store the internet. When you use the internet, you’re using a data center.

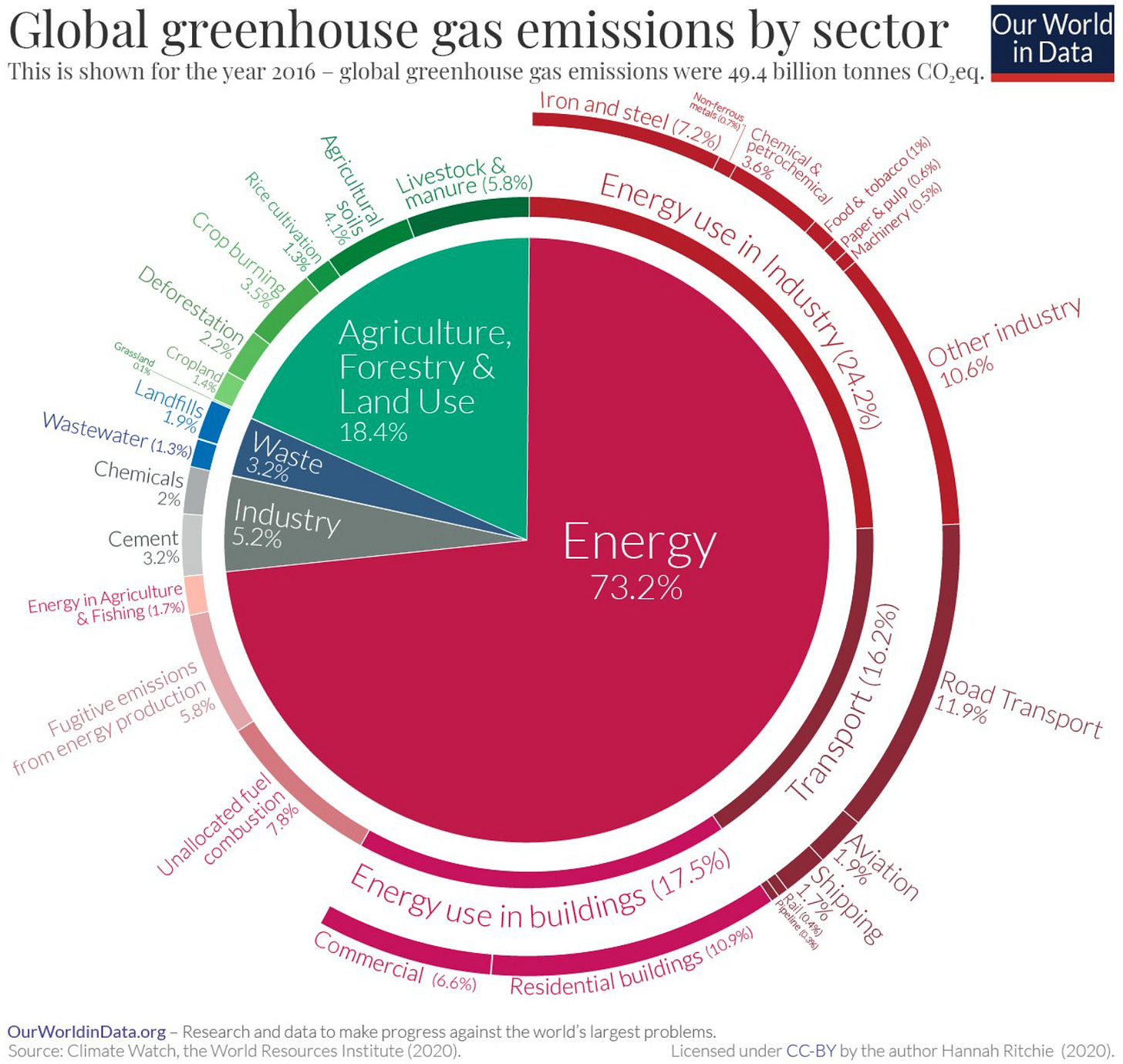

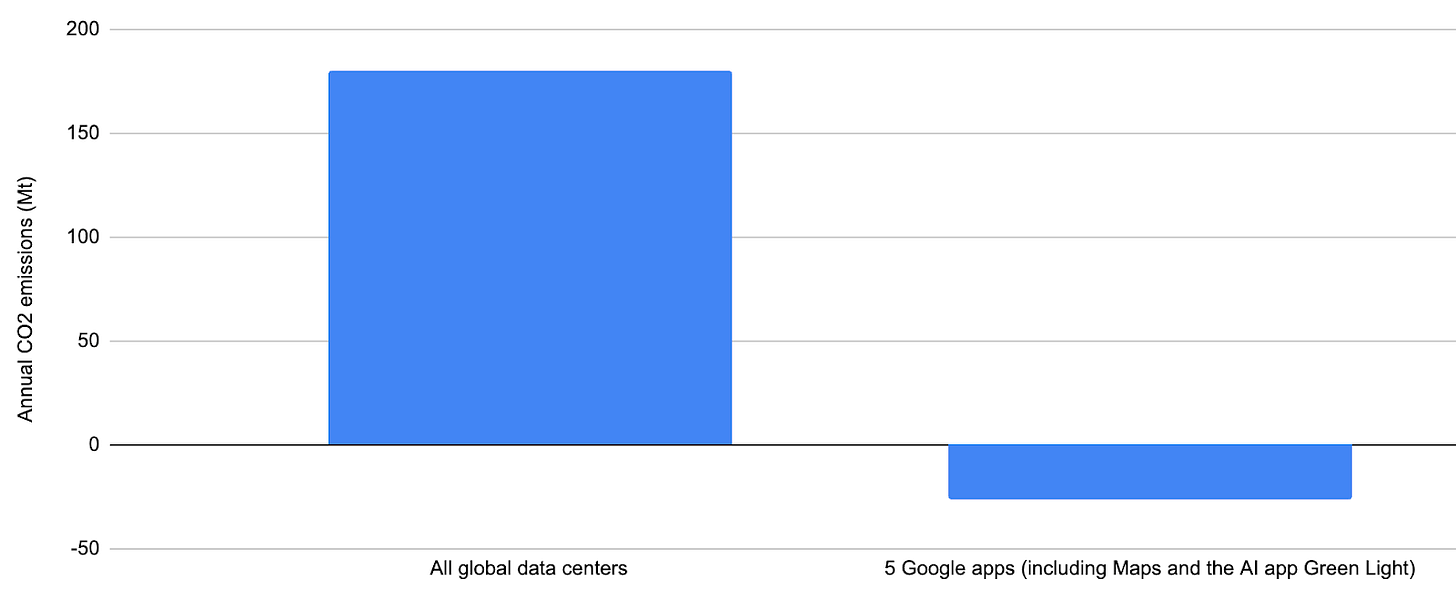

All data centers worldwide emitted roughly 180 million tonnes of CO₂ in 2024, about 0.5% of the world’s annual emissions.

At first, this may seem high. Half a percentage of global emissions is still higher than some countries, because there are ~200 countries. Even if each country were the same size, each would be half a percentage of the world’s emissions. People sometimes point out that data centers globally are emitting more CO2 than countries like the Philippines.

But if everyone on Earth were spending half their waking lives every single day interacting with the Philippines, it makes sense that the country’s emissions would at least double. It would probably skyrocket way higher than that! It should be physically impossible to build a ton of buildings that everyone on Earth uses for half the day every day that would somehow only emit as much as the Philippines, that would only be 0.5% of all emissions, and yet we’ve done it! That’s a miracle!

America is currently going through a buildout of new AI data centers. 51% of all hyperscale AI facilities in the world are in America, and 60% of new ones will be built here. These data centers are supporting users around the world, not just in America. We’re making building-sized computers that people around the world can log into and use to access AI tools. About a billion people use AI. The last year we have great data on America’s AI energy usage is 2023, when it used about 40 TWh. If we guess AI energy increased by 20% in 2024, and that 500 million people were interacting with AI in 2024 (the actual number is probably much higher, because AI is built into a lot of what we do online now), then for each person using an American AI data center, the data center used about 96 kWh of energy in 2024 per user, 0.5% of the average global citizen’s annual energy usage, and just 0.2% of the average American’s. This is a rough estimate, but if you actually include a rough guess of how many people globally are interacting with AI and how many of those people are interacting with US data centers, AI data centers in America still appear remarkably energy efficient.

What about water? Well the water that was actually used onsite in American data centers was only 50 million gallons per day in 2023, the rest was used to generate electricity offsite. Only 0.04% of America’s freshwater in 2023 was consumed inside data centers themselves. Data centers consumed just 3% of the water used by the American golf industry in the same year. Forecasts imply that American data center electricity usage could triple by 2030. Because water use is approximately proportionate to electricity usage, data centers may consume 150 million gallons of water per day onsite, 0.12% of America’s current consumptive freshwater use.

So the water all American data centers will consume onsite in 2030 is equivalent to:

The water usage of 260 square miles of irrigated corn farms, equivalent to 1% of America’s total irrigated corn.

The total projected onsite water consumption of all American data centers is incredibly small by the standards of other ways water is used. Again, consider that these small amounts of water are being used on something we all spend half our lives using.

The real environmental problem with data centers is that they concentrate so much specific electricity demand into such small specific places that the surrounding grid often cannot keep up, and needs to rely more on fossil fuel plants, or onsite gas turbines. This is serious, but to think seriously about this problem, people need to understand that this high demand is not coming from any wasted energy in the data center itself, it’s that there are hundreds of thousands of people invisible to us who are interacting with any one of them at a given time. Concentrating this demand actually makes them more energy efficient, due to economies of scale. The larger the data center, the more efficient it tends to be. So all else being equal, if you want a computer application to use the least energy possible, you should prefer that it be in the largest data center possible, even though this data center will put more strain on the surrounding grid.

On top of all this, anything that uses electricity is going to be much easier to decarbonize than most parts of the economy. The total electricity sector is only responsible for 25% of global emissions. The much bigger challenge is going to be vehicles and industrial processes that use fossil fuels directly. If we transition to a clean grid, the vast majority of the environmental problems with data centers will be solved.

The national microwave example

One of the most important facts about climate change is that where emissions happen is counter-intuitive, often hidden from us. Using a computer for hours doesn’t add nearly as much to your daily carbon footprint as eating a burger, but the computer feels more energy intensive than your lunch.

The climate does not react to which industry emits or which specific buildings emit. It only reacts to the total CO2 in the air.

The national microwave

If data centers didn’t exist, we would need to rely on our personal computers to run everything we do online. When you logged into YouTube, you’d run YouTube software on your own computer like it was a video game, and save all videos you upload on your own computer. Every time someone else wanted to watch your videos, they would need to connect to your computer like other players on a video game can connect to a game you’re running. The magic of data centers is that by piling huge amounts of computing in one place, you can make all that computing more energy-efficient than it would be otherwise, and more accessible for everyone involved.

Other things don’t work this way. If I want to microwave something, I have to own my own microwave. I can’t send things off to some centralized microwave somewhere else.

What if I could?

Let’s say there were a single national microwave. When you needed food heated up, you would teleport the food to the national microwave, in the same way you effectively teleport information from your computer to data centers.

This microwave would need to be massive to fit all microwaved meals Americans are making at any given time.

I estimate that all microwaves in America use ~25 GWh of electricity every day. This means that the big national microwave would be using as much electricity every day as Seattle. An entire new city’s worth of electricity demand added to the grid, just for heating food!

What about the water? Well the average water consumption per kWh in American power plants is 4.35 L, so this microwave would be consuming 110,000,000 liters of water every single day. 45 Olympic pools of water every day.

I think if the big national microwave existed, it would be drawing a lot of scorn. “This seems so wasteful. What’s wrong with just using an oven?” People would see it as sapping a whole city’s worth of energy. There would be articles about how it’s sapping the local grid and using as much energy as 800,000 households.

But this microwave does exist. It’s just hidden, broken up into hundreds of millions of little pieces of itself scattered across America. The impacts are just as real as if it existed in one place. The climate does not care about where emissions happen. It just responds to total emissions. All microwaves in America are emitting just as much as the big national microwave would. But they don’t exist in one place as a single evil building people can get mad at. The big national microwave is invisible.

Suppose someone says “Tech bros just reinvented the oven, only this time it’s destroying the planet.” Would we want people to stop using the big microwave and switch to their ovens?

Well, ovens use way more energy to cook the same food. Getting people to stop using the big microwave and switch to ovens would actually cause way more emissions in total, probably around 10 times as much. Those emissions would just be dispersed across the country, so people would feel better about them, because they couldn’t see them. People really like when they can’t actually see the effects they’re having on the climate, but those effects are still real. Shutting down the big national microwave would be a huge environmental mistake, even though it looks much more evil than everyone’s individual ovens.

These are three mistakes I think people would make if we had the big national microwave:

They would only see it as a single, inert building using a ton of energy, and wouldn’t compare its benefits per unit emissions to other buildings. They wouldn’t consider how many more people were interacting with it, or divide the energy cost by the number of people using it. It would make sense that a building managing all microwave needs for all America would be using more energy than a nearby toy store, because it would be serving a lot more people. The toy store is actually way more inefficient with its energy, but comparing it to the toy store would be ridiculous. If it sounds ridiculous to say “All American microwaves are using more energy than this one toy store, people should all throw away their microwaves!” then it should sound equally ridiculous to condemn the big national microwave for the same reason.

They would want to shut it down and have switch to things that seem more “normal” like using an oven, even though those normal things are mostly way worse for the climate. The normal things don’t have a big evil building of their own to represent how much energy they’re really using, so unlike the microwave, their emissions are invisible, even though they’re much greater in total.

They would only see the building as using a lot of energy relative to everyday people (800,000 households!) and wouldn’t consider it in the context of climate overall and how big of a problem it is compared to most other things we do. They would prioritize optimizing the microwave over much more easy climate wins, like shutting down coal plants or electrifying cars.

People also make these three mistakes when thinking about data centers. When you see climate arguments against data centers, check and see if the same arguments would apply to the national microwave, and wouldn’t apply to regular microwaves. That tells you that the other person is just mad that emissions are visible, not that they’re a lot.

Data centers as the national microwave

Data centers are weird buildings. They concentrate more power demand in a smaller space than basically any other type of building. They also, at any one moment, have hundreds of thousands of people from around the world interacting with them.

From the outside, data centers look boring and inert.

But in some sense they’re the most active physical objects we’ve ever built. They’re building-sized computers constantly running gigantic amounts of equations. Microsoft’s 2023 GPT-4 training cluster reportedly had ~25,000 A100 GPUs in a single build. This amount of chips could perform around 1018 (million trillion) addition or multiplication calculations per second. All humans who have ever lived, doing one calculation per second for 24 hours per day, could together do that many calculations in about 100 days.

Each data center is more of a massive very general tool than a normal building.

Like the national microwave, hundreds of thousands of people interact with a data center at once. People effectively teleport computer tasks away for some far off building to deal with it much more efficiently and reliably. When you read stories about data centers using huge amounts of power, you should think “This is because tens of thousands of people are interacting with the building at once and using it as a tool, like a gigantic national calculator.” You might think the way the data center’s being used is bad or wasteful, but you should still hold in your head that this is just a very very concentrated result of 10s of thousands of small individual decisions, like the microwave is.

Data centers are uniquely energy-efficient. Basically all the energy they take in is delivered directly to incredibly optimized computer tasks. They’re the most energy-efficient way to do a lot of computing. Since computing can give us valuable information about the world, it seems good to be able to build these huge clusters where computing can happen more efficiently than anywhere else.

AI forecasts are very uncertain, but some imply that AI will on net be net good for emissions

It is famously difficult to predict how AI progress will play out, but most expert predictions of AI’s net effects on the climate lean in the direction that it will on net prevent more emissions than data centers cause. The International Energy Agency says:

The adoption of existing AI applications in end-use sectors could lead to 1400 Mt of CO2 emissions reductions in 2035 in the Widespread Adoption Case. This does not include any breakthrough discoveries that may emerge thanks to AI in the next decade. These potential emissions reductions, if realized, would be three times larger than the total data centre emissions in the Lift-off Case, and four times larger than those in the Base Case.

That’s the current total yearly emissions of all global shipping and aviation. Seems good!

Summary

So what does this mean for your individual AI prompts?

Stories of AI data centers using a lot of local resources are due to them concentrating global demand for AI in very concentrated buildings, not each individual prompt using a lot of energy. In the equation Total energy = (Energy per prompt) x (Number of prompts), it’s the number of prompts that’s large, not the energy per prompt.

Usually, the larger the data center, the more energy-efficient it is. Computing in data centers is much more energy-efficient than on your computer.

The fact that AI prompts are run in a big data center makes them no worse for the climate than if you ran them on your personal computer, because the climate does not respond to where emissions happen, only total emissions. Data centers draw from energy sources that are more carbon intensive than normal, but the emissions from your individual prompts still round to zero compared to basically every other way you spend your time. Reducing your individual AI prompts will have no impact in your emissions.

Many people have trouble visualizing the aggregate results of doing everyday activities. If there were a single national microwave, it would use as much energy every day as Seattle. Data centers make this aggregate energy use visible, but the aggregate energy of most other ways we spend our time are invisible. Data centers only look like they’re using way more energy because we can’t directly see all the energy of other things we do gathered together into specific buildings.

If you are worried about the local environmental impacts of data centers, the way to solve them will be regulation from local governments, not individual consumer boycotts. Data centers concentrate so many prompts in one place that even large amounts of people boycotting AI wouldn’t change how much an individual data center emits.

Everything you do online involves interacting with data centers. We shouldn’t be surprised that buildings we spend half our time interacting with are using a noticeable amount of energy. It’s still incredibly small compared to most other things we do.

Globally, forecasts for how much energy data centers will use into 2030 and beyond seem pretty underwhelming, especially when you consider that everyone on Earth is spending half their time interacting with them.

Data centers are not inert buildings that just burn through energy and resources for no reason. They’re building-sized computers that have been uniquely optimized to do complex computing tasks. Of all the ways that we can spend energy as a society, they seem more useful than many other options.

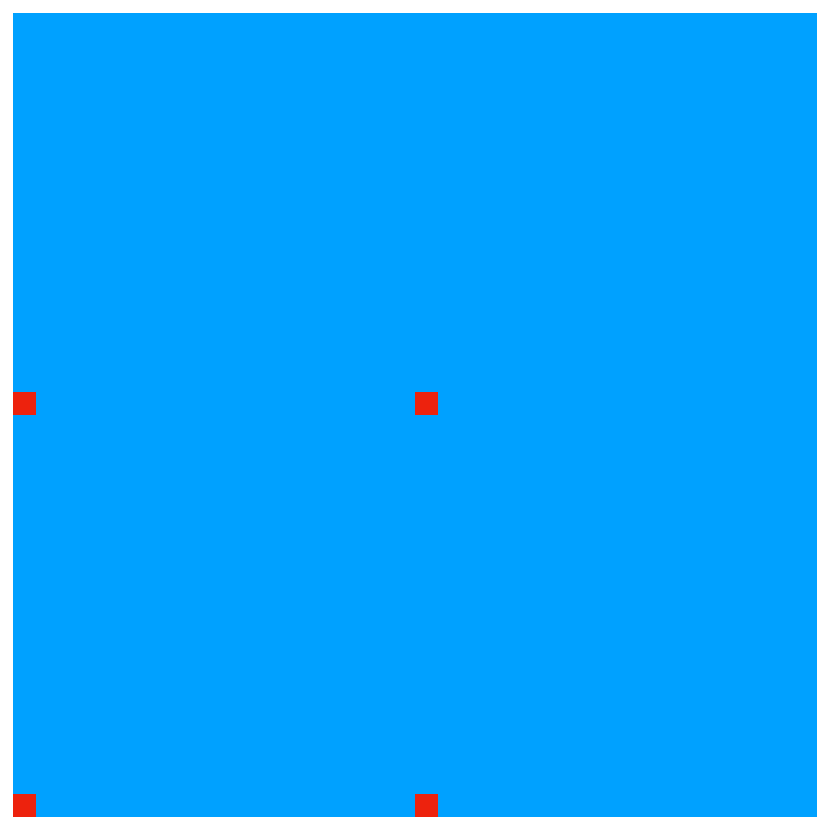

AI is using so much energy that it’s causing new fossil fuel plants to open, which we can’t afford in a climate crisis

It doesn’t matter where emissions happen, what matters is the total

It’s true that there have been places where AI data centers have caused fossil fuel plants to reopen. AI’s putting new concentrated energy demands in a lot of specific places.

The climate does not react to where on Earth emissions happen, it only reacts to how much in total is emitted. I worry that when people focus on new fossil fuel plants, they’re basically normalizing the old ones and treating them as emissions that have somehow already happened. They’re treating all other sources of emissions as “normal” in some way:

I think it makes a lot more sense to think about emissions like this:

We are trying to stop as many of those emissions as possible, but we can’t cut all emissions right this moment. Billions would die if we did that. The world is still too fundamentally dependent on fossil fuels. So we need to work hard to transition society off of fossil fuels, and in the meantime cut specific emissions. We can’t just cut emissions blindly. Some of those emissions are used to power hospitals, others to private jets. Some emissions add up to tiny tiny amounts of the total, others are significant. Which emissions we work to stop should be determined by 2 things:

Where we have the opportunity to prevent the most emissions.

Which emissions are most wasteful and unnecessary to living a good life.

Whether the emissions are happening in an old or new fossil fuel plant doesn’t really matter. If I went out and built a small coal plant to power my personal home, that would be bad, but it wouldn’t be anywhere near as bad as the aviation industry just because it’s new. Even though my fossil fuel plant is “new,” all the emissions around the world are the same type of thing: CO2. It doesn’t matter where CO2 is coming from, what matters is how much of it each industry is emitting and where we can cut the most. Every day we wake up and add a ton of “new” emissions. Every time we drive or use electricity or burn fossil fuels in any way, we’re adding new emissions. That’s what really matters, not the physical power plant those emissions happen in.

Suppose an industry relies on a nearby coal plant. Suddenly, the industry starts using twice as much electricity, causing the nearby plant to burn twice as much coal and emit twice as much. This is identical to the industry causing a second nearby coal plant to open. In both cases, the same total emissions are happening, they’re just coming from different physical buildings. In this sense, all industries are equally responsible for the “opening of new fossil fuel plants” in that they are all contributing different amounts to total CO2 emissions. The excessive focus on new plants doesn’t on its own make sense.

Does this make sense if we think about AI stopping our climate progress?

I think when a lot of people say they’re worried about AI opening fossil fuel plants, what they really mean is that they’re worried AI is using so much new power that it’s stopping the global transition to clean energy. This makes a lot more sense.

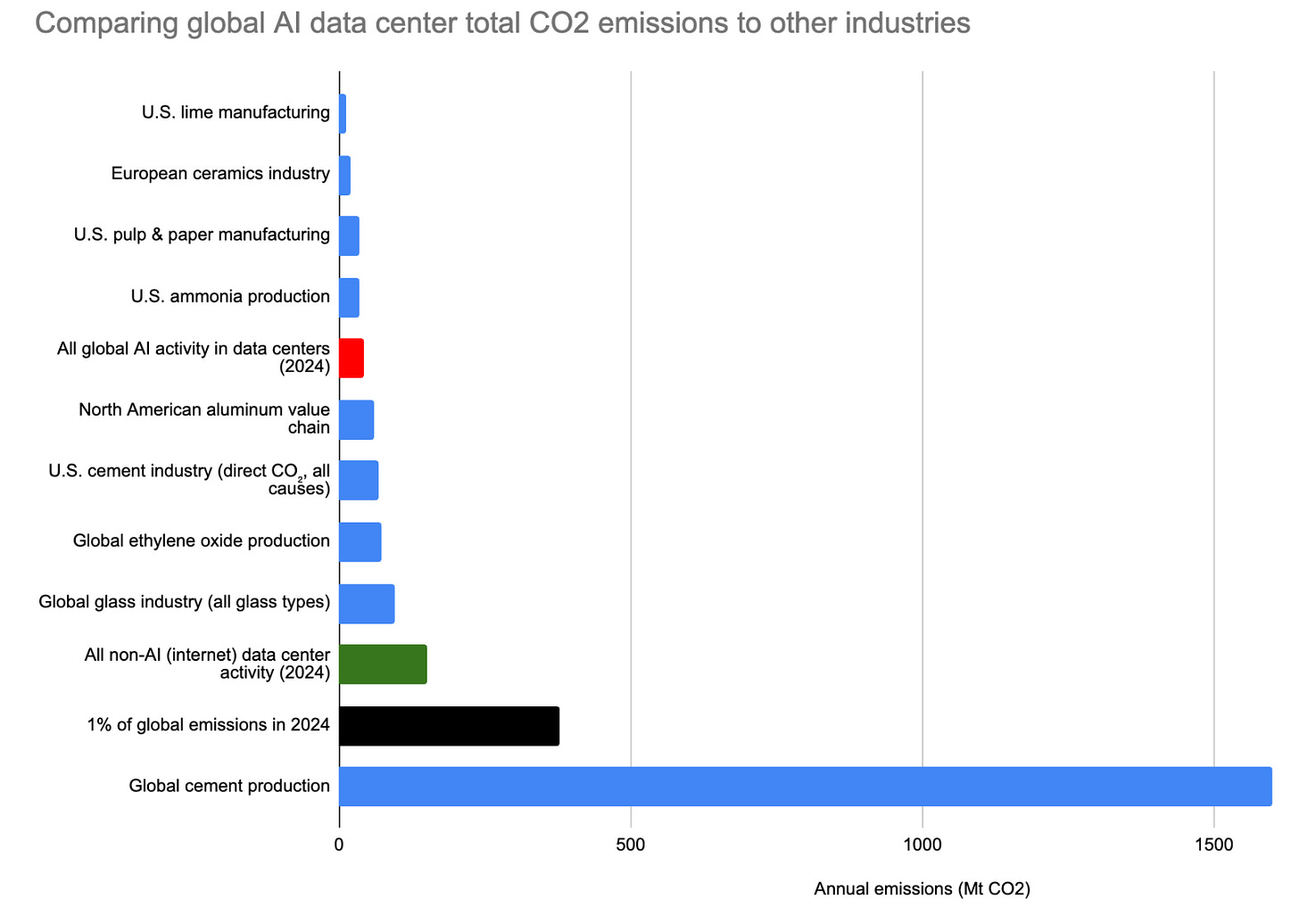

But all AI in all data centers in total caused roughly 43million tonnes of CO₂ in 2024, about 0.11% of the world’s annual emissions. This was less than the US aluminum market:

All AI activity in all global data centers in 2024 emitted about 2% as much as cement production. If we could optimize cement production just 2% more, this would do as much good as stopping all AI services globally. As it happens, AI has a lot of potential applications to optimize cement production, so it itself might reduce cement emissions by 2% and net out to zero emissions. It can do this because it’s both a tiny part of global emissions and uniquely good at optimizing other processes.

AI isn’t actually significantly contributing to global emissions when you consider the scale of use. Roughly a billion people are now using AI weekly, but it’s only adding 1/1000th to global emissions. There is basically no other service that a billion people use every week that is emitting so little.

Complicating this picture more is AI’s potential to optimize services to limit carbon emissions. It is famously difficult to predict how AI progress will play out, but most expert predictions of AI’s net effects on the climate lean in the direction that it will on net prevent more emissions than data centers cause. The International Energy Agency says:

The adoption of existing AI applications in end-use sectors could lead to 1400 Mt of CO2 emissions reductions in 2035 in the Widespread Adoption Case. This does not include any breakthrough discoveries that may emerge thanks to AI in the next decade. These potential emissions reductions, if realized, would be three times larger than the total data centre emissions in the Lift-off Case, and four times larger than those in the Base Case.

So in a world where we adopt AI in more parts of the economy faster, it looks like on net it will prevent more total emissions. If we achieve the high adoption situation the IEA describes, it will on net reduce global emissions by 1100 Mt of CO2 each year. That’s the current total yearly emissions of all global shipping and aviation.

Of all the things to cut to maximally help the climate, AI does not seem like a promising target. It is uniquely good at optimizing complex processes, which is something we desperately need across all sectors to make the green transition go better. If I were making a list of sectors to cut for the climate, AI would be very very far down. Everything we do on computers is incredibly energy optimized compared to most other parts of society.

Putting AI’s 0.11% of global emissions into global perspective, and comparing it to other industries, makes it seem pretty marginal compared to most climate issues. If AI is the “tipping point” that stops us from solving climate change, technically so is the marginal 2% of global cement production:

One last note here is that decarbonizing the economy is going to be easiest for anything that runs entirely on electricity. The real challenge is going to be places where fossil fuels are used directly, like vehicles and industry. Because data centers rely exclusively on electricity, all their climate issues can be solved by a transition to clean energy. They’re not at all locking in fossil fuels in the way industry and vehicles currently are.

Data centers harm local water access

This one’s actually just false. I have a much longer deep dive on this here. There is nowhere in America where data center operational use of water has increased household water prices at all. Why is this?

Data centers are not using that much water

All U.S. data centers had a combined consumptive use of approximately 200–250 million gallons of freshwater daily in 2023. The U.S. withdraws approximately 280 billion gallons of freshwater daily. Data centers in the U.S. consumed approximately 0.09% of the nation’s freshwater in 2023. I repeat this point a lot, but Americans spend half their waking lives online. Everything we do online interacts with and uses energy and water in data centers. It’s kind of a miracle that something we spend 50% of our time using only consumes 0.09% of our water.

However, the water that was actually used onsite in data centers was only 50 million gallons per day, the rest was used to generate electricity offsite. Only 0.02% of America’s freshwater in 2023 was consumed inside data centers themselves. This is 3% of the water consumed by the American golf industry. Forecasts imply that American data center electricity usage could triple by 2030. Because water use is approximately proportionate to electricity usage, this implies data centers themselves may consume 150 million gallons of water per day onsite, 0.06% of America’s current freshwater use.

So the water all American data centers will consume onsite in 2030 is equivalent to:

The water usage of 260 square miles of irrigated corn farms, equivalent to 1% of America’s total irrigated corn.

The total projected onsite water consumption of all American data centers is incredibly small by the standards of other ways water is used.

In 2023 all data centers in America collectively consumed as much water as the lifestyles of the residents of Paterson, New Jersey. AI uses ~15% of energy in data centers globally. It seems unlikely AI in America specifically is even half of the water footprint of Paterson. If we just include the water used in data centers themselves, this drops to the water footprint of the population of Albany, New York.

Water economics

America is good at water economics. Our water management has a lot of ways to keep rates low for consumers. This (and AI’s very low total use of water) is the main reason it hasn’t affected water prices at all.

Household and commercial water prices are different everywhere to keep the markets separate so commercial buildings aren’t competing with homeowners. Data centers only compete with other businesses for water, like any other industry.

In low water scarcity areas, water isn’t zero sum. More people buying water doesn’t lead to higher prices, it gives the utility more money to spend on drawing more water and improve infrastructure. It’s the same reason grocery prices don’t go up when more people move to a town. More people shop at the grocery store, which allows the grocery store to invest more in getting food, and they make a profit they can use to upgrade other services, so on net more people buying from a store often makes food prices fall, not rise. Studies have found that utilities pumping more water, on average, causes prices to fall, not rise.

The only times water costs rise in low water stress areas when a large new consumer arrives is when the consumer demands so much water that utilities are forced to do major rapid upgrades to their systems, and the consumer doesn’t pay for those upgrades. In every example I can find of data centers requiring water system upgrades, the companies that own the data centers are the main source of revenue used.

The main water issue in American small towns isn’t the supply of water, it’s aging water infrastructure that doesn’t serve a large or rich enough tax base to get the money to upgrade. Old infrastructure makes water more expensive. It can also be dangerous (lead pipes etc.). Small town water costs are often higher, not lower, than cities, due to economies of scale. This wouldn’t happen if water costs simply rose when more water is used. Data centers moving into small towns often provide utilities with enough revenue to upgrade their old systems and make water more, not less, accessible for everyone else.

In high water scarcity areas, city and state leaders have already thought a lot about water management. They can regulate data centers the same ways they regulate any other industries. Here water is more zero sum, but data centers just end up raising the cost of water for other private businesses, not for homes. Data centers are subject to the economics of water in high scarcity areas, and often rely more on air cooling rather than water cooling because the ratio of electric costs to water costs is lower.

This seems fine if we think of data centers as any other industry. Lots of industries in America use water. AI is using a tiny fraction compared to most, and generating way, way more revenue per gallon of water consumed than most. Where water is scarce, AI data centers should be able to bid against other commercial and industrial businesses for it.

In general, if there’s a public resource like water, it’s considered the job of the utility and government to set rates to reflect its scarcity. Blaming a private business like a data center for using too much water seems kind of like blaming private customers for buying too much food from a grocery store. It’s the grocery store’s responsibility to set prices to reflect the relative scarcity of and demand for different products. If people are buying too much food from the store and there’s not enough money to restock, that’s the fault of the store, not the individuals. Private businesses shouldn’t be expected to monitor the exact state of local water to decide how much is ethical to buy from the utility. It’s the utility’s job to limit demand by setting prices higher if they actually think the company is going to harm the local water system. If utilities set prices high enough, data centers adjust by switching to different types of cooling systems that use less or no water. The market is (like in most places) the way that data centers receive information about the relative scarcity of water. In most conversations about AI and water, the responsibility for water management is oddly shifted to the private company in a way we don’t do for any other industry.

Politicians especially have strong motivations to keep household water prices low. Voters get mad when utility costs rise.

There are many cases of data centers being built, providing lots of tax revenue for the town and water utility, and the locals benefiting from improved water systems. Critics often read this as “buying off” local communities, but there are many instances where these water upgrades just would not have happened otherwise. It’s hard not to see it as a net improvement for the community. If you believe it’s possible for large companies using water to just make reasonable deals with local governments to mutually benefit, these all look like positive-sum trades for everyone involved.

Here are specific examples:

The Dalles, Oregon - Fees paid by Google fund essential upgrades to water system.

Council Bluffs, Iowa - Google pays for expanded water treatment plant.

Quincy, Washington - Quincy and Microsoft built the Quincy Water Reuse Utility (QWRU) to recycle cooling water, reducing reliance on local potable groundwater; Microsoft contributed major funding (about $31 million) and guaranteed project financing via loans/bonds repaid through rates. These improvements increase regional water resilience beyond the data center itself.

Goodyear, Arizona - In siting its data centers, Microsoft agreed to invest roughly $40–42 million to expand the city’s wastewater capacity—utility infrastructure the city highlights as part of the development agreement and that increases system capacity for the community.

Umatilla/Hermiston, Oregon - Working with local leaders, AWS helped stand up pipelines and practices to reuse data-center cooling water for agriculture, returning up to ~96% of cooling water to local farmers at no charge. That 96% is from AWS itself, not sure if it’s correct.

I could go on like this for a while. Maybe you think every one of these is some trick by big tech to buy off communities, but all I’m seeing here is an improvement in local water systems without any examples of equivalent harm elsewhere

In general, the US has a lot of freshwater.

America has among the cheapest water costs of any nation in the world.

Because we’re also the richest nation in the world, our water costs are incredibly low as a percentage of per capita income.

AI as a normal industry

If a steel plant or college or amusement park were built in a small town, it would be normal for it to use a lot of the town’s water. We wouldn’t be shocked if the main industry in the town were using a sizable amount of the water there. If it provided a lot of tax revenue for the town and was not otherwise harming it, I think we would see this as a positive, and wouldn’t talk in an alarmed way about the specific percentages of the town’s water the industry was using. We should think of AI like we do any other industry. A data center drops into a town, draws water in the same way a factory or college would, the local system adapts to it quickly, and residents benefit from the tax revenue. The industry could provide enough water payments or tax revenue to improve the town’s water supplies in the first place.

In Texas, data centers paid an estimated $3.21 billion in taxes to state and local governments in 2024. There is no exact figure on total data center water use in Texas in 2024, but there are forecasts that they will use ~50 billion gallons of water in 2025. So excluding the price data centers pay for the water and energy they use, data centers are paying about $0.064 in tax revenue per gallon of water they use. The cost of water in Texas varies between $0.005 and $0.015 per gallon. Even if data centers caused water prices to quadruple, they would still ultimately be paying more back to local communities than the communities lost in additional water prices. This pattern holds everywhere data centers are built. They add huge amounts of tax revenue to local and state economies that seem to more than balance out any negative water externalities.

xAI’s Colossus in Memphis polluted a local poor community

This seems like the most likely place where an AI data center created significant harm. To put it mildly, I don’t trust Elon Musk, and wouldn’t rely on him to make good decisions here. Here’s what we know about what happened with Colossus:

xAI’s Colossus is the largest AI supercomputer in America as of writing, with the highest power demand. xAI installed 35 onsite natural gas turbines to supplement the grid, and began operations in June 2024 without necessary air permits from the Shelby County Health Department (SCHD), according to thermal imaging of the site.

The nearby community were already victims of significant air pollution with local air receiving an F grade in quality. Community members registered a significant change in the smell of the air after xAI began operations, to the point that some experienced significant asthma issues. Environmental protection groups raised concerns. The Southern Environmental Law Center estimated that the unregulated turbines could emit 1,200–2,000 tons of NOx per year and potentially exceed the major source threshold for hazardous air pollutants (HAPs) like formaldehyde. A more recent estimate from a team of public and environmental health researchers at the nearby University of Memphis called this number into question, arguing that xAI’s contributions to local air pollution were minimal. The city government performed air quality tests that did not detect changes in air quality due to the data center, but critics argued that the tests were poorly designed and did not measure key pollutants.

The regulatory response culminated in July 2025, when the SCHD issued a construction permit with strict annual emission caps (87.14 tons of NOx per year, lowering total potential emissions by a factor of 12-21). This resolution demonstrates that while initial unregulated operation posed a significant risk, the application of stringent, utility-grade pollution controls can drastically reduce the emissions effect.

I basically don’t know what the final story is here, but am inclined to trust local community members here over xAI.