AI data centers use water. Like any other industry that uses water, they require careful planning. If an electric car factory opens near you, that factory may use just as much water as a data center. The factory also requires careful planning. But the idea that either the factory or AI is using an inordinate amount of water that merits any kind of boycott or national attention as a unique serious environmental issue is innumerate. On the national, local, and personal level, AI is barely using any water, and unless it grows 50 times faster than forecasts predict, this won’t change. I’m writing from an American context and don’t know as much about other countries. But at least in America, the numbers are clear and decisive.

The idea that AI’s water usage is a serious national emergency caught on for three reasons:

People get upset at the idea of a physical resource like water being spent on a digital product, especially one they don’t see value in, and don’t factor in just how often this happens everywhere.

People haven’t internalized how many other people are using AI. AI’s water use looks ridiculous if you think of it as a small marginal new thing. It looks tiny when you divide it by the hundreds of millions of people using AI every day.

People are easily alarmed by contextless large numbers, like the number of gallons of water a data center is using. They compare these large numbers to other regular things they do, not to other normal industries and processes in society.

Together, these create the impression that AI water use is a problem. It is not. Regardless of whether you love or hate AI, it is not possible to actually look at the numbers involved without coming to the conclusion that this is a fake problem. This problem’s hyped up for clicks by a lot of scary articles that completely fall apart when you look at the simple easy-to-access facts on the ground. These articles have contributed to establishing fake “common wisdom” among everyday people that AI uses a lot of water.

This post is not at all about other issues related to AI, especially the very real problems with electricity use. I want to give you a complete picture of the issue. I think AI and the national water system are both so wildly interesting that they can be really fun to read about even if you’re not invested in the problem.

Contents

AI water use isn’t an issue on the national, local, or personal level

Using AI can save way more water than is used in data centers

The social value or harm of a tool isn’t the final word on how harmful it is to the environment

What about all those news stories about AI harming local water access?

AI water use isn’t an issue on the national, local, or personal level

National

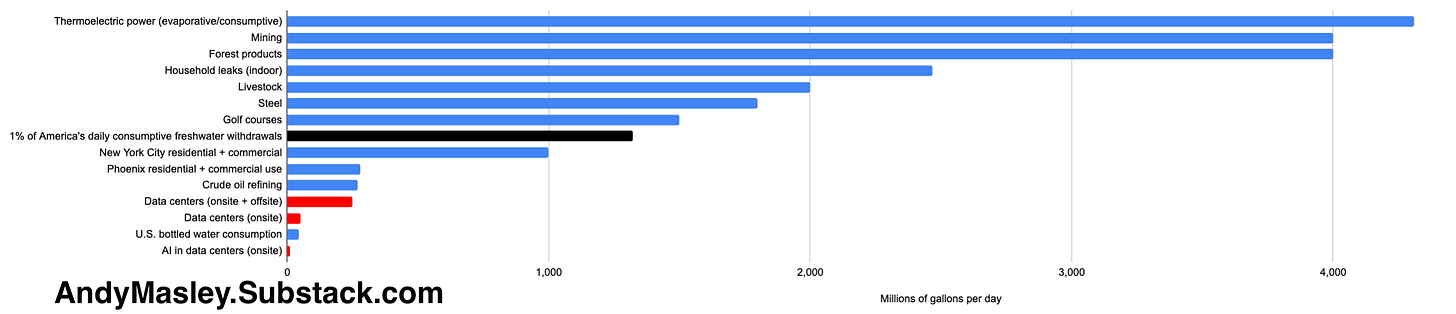

All U.S. data centers (which mostly support the internet, not AI) used 200–250 million gallons of freshwater daily in 2023. The U.S. consumes approximately 132 billion gallons of freshwater daily. The U.S. circulates a lot more water day to day, but to be extra conservative I’ll stick to this measure of its consumptive use, see here for a breakdown of how the U.S. uses water. So data centers in the U.S. consumed approximately 0.2% of the nation’s freshwater in 2023. I repeat this point a lot, but Americans spend half their waking lives online. A data center is just a big computer that hosts the things you do online. Everything we do online interacts with and uses energy and water in data centers. When you’re online, you’re using a data center as you would a personal computer. It’s a miracle that something we spend 50% of our time using only consumes 0.2% of our water.

However, the water that was actually used onsite in data centers was only 50 million gallons per day, the rest was used to generate electricity offsite. Most electricity is generated by heating water to spin turbines, so when data centers use electricity, they also use water. Only 0.04% of America’s freshwater in 2023 was consumed inside data centers themselves. This is 3% of the water consumed by the American golf industry.

How much of this is AI? Probably 20%. So AI consumes approximately 0.04% of America’s freshwater if you include onsite and offsite use, and only 0.008% if you include just the water in data centers.

So AI, which is is now built into every facet of the internet that we all use for 7 hours every single day, that includes the most downloaded app for the 7 months straight, that also includes many normal computer algorithms beyond chatbots, and that so many people around the world are using that Americans only make up 16% of the user base, is using 0.008% of America’s total freshwater. This 0.008% is approximately 10,600,000 gallons of water per day.

I’m from a town of 16,000 people. It looks like this:

All AI in all American data centers is collectively using 8 times as much water as the local water utility in my town provides to consumers.1 You should be exactly as worried about AI’s current national water usage as you would be if you found out that 8 additional towns of 16,000 people each were going to be built around the country.

Here’s data center water use compared to a lot of other American industries:

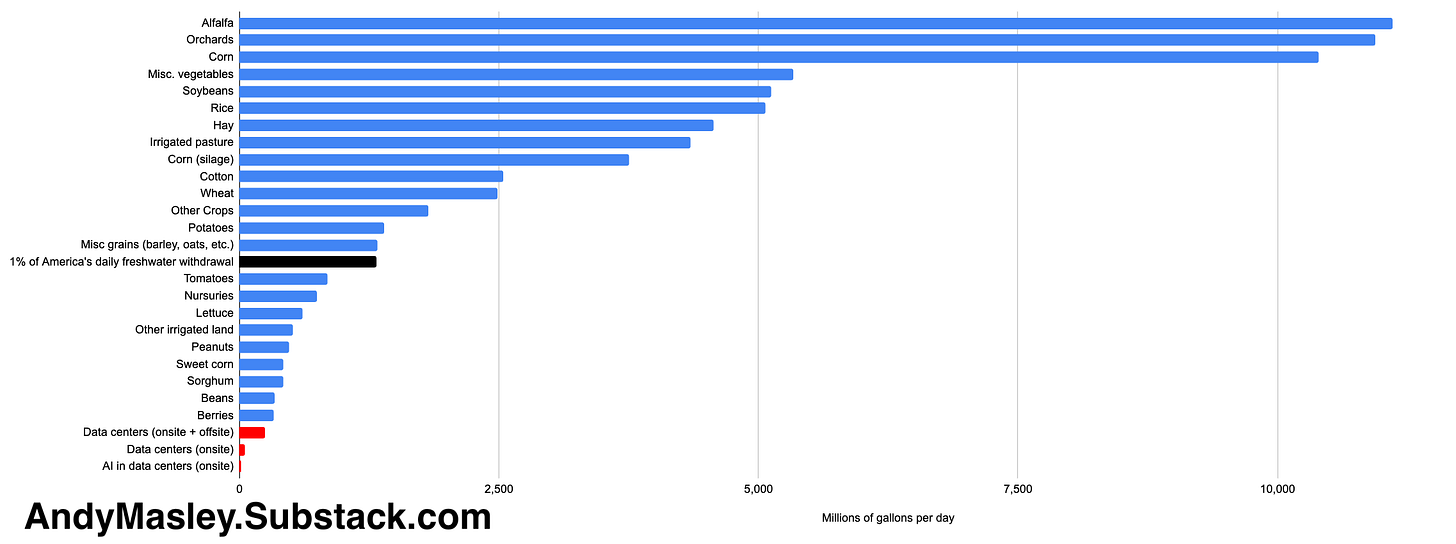

And here’s a comparison to how much water different American agricultural products use, the main way water is used in America:

Forecasts imply that American data center electricity usage could triple by 2030. Because water use is approximately proportionate to electricity usage, this implies data centers themselves may consume 150 million gallons of water per day onsite, 0.12% of America’s current freshwater consumption.

So the water all American data centers will consume onsite in 2030 is equivalent to:

8% of the water currently consumed by the U.S. golf industry.

The water usage of 260 square miles of corn farms, equivalent to increasing America’s corn production by 1.4%.

If you found out that U.S. steel production was expected to increase by 8% in 2030, the amount that would cause you to worry about water is how worried you should be about data center water usage by 2030.

How much of this will be AI? Almost all this growth will be driven by AI, but because AI is only 20% of data center power use, its growth will have to be huge to triple total power usage. One forecast says AI energy use in America will be multiplied by 10 by 2030. Because water use is proportionate to energy use, we can multiply AI’s water use by 10 as well.

So in 2030, AI in data centers specifically will be using 0.08% of America’s freshwater. This means it will rise to the level of 5% of America’s current water used on golf courses, or 5% of U.S. steel production, or be about 173 square miles of corn farms.

The average American’s consumptive lifestyle freshwater footprint is 422 gallons per day. This means that in 2023, AI data centers used as much water as the lifestyles of 25,000 Americans, 0.007% of the population. By 2030, they might use as much as the lifestyles of 250,000 Americans, 0.07% of the population. Not nothing, but 250,000 people over 5 years is just 4% of America’s current rate of population growth. If you found out that immigration plus new births in America would increase by 4% of its current rate, would you first thought be “We can’t afford that, it’s way too much water”?

This is more contentious, but all this is in the context of AI potentially boosting U.S. and global GDP by whole percentage points. Most forecasts imply that AI will boost total U.S. GDP by at least 1%. If we judge industries by how much they’re contributing, data center direct onsite usage will collectively be 0.08% of consumption by 2030, but contributing at least 1% to GDP. Maybe this won’t happen, but in worlds where this doesn’t happen, AI companies won’t be able to afford a huge buildout either. If AI is a bubble, the bubble will have to pop sometime before AI data center water usage hits 10x what it currently is in America. Your predictions for how much water AI will use and your predictions for how much real economic value it’s going to provide have to be related in some way.

Local

Data center operational use of water doesn’t limit water access anywhere they’re built

Because data centers are using the same normal amounts of water as many other industries, there are no places (so far) where it seems like data centers have raised water costs at all or harmed local water access. I have a much longer deep dive on that here. I won’t repeat all the arguments. If you’re skeptical, I’d suggest reading that first.

The only exceptions to this rule are the construction of data centers, which has in a few place caused issues for local groundwater. This is bad, but it’s purely an issue of constructing a large building. It has nothing to do with AI specifically, for the same reason that debris from a bank being constructed would tell you nothing about how banks normally impact a community. There’s a famous New York Times headline that comes up in most conversations of AI and water use:

But the reason their taps ran dry (which the article itself says) was entirely because of sediment buildup in groundwater from construction. It had nothing to do with the data center’s normal operations (it hadn’t begun operating yet, and doesn’t even draw from local groundwater). The residents were wronged by Meta here and deserve compensation, but this is not an example of a data center’s water demand harming a local population.

Basically every single news story that’s broken about this has been misleading for similar really simple reasons it’s easy to cross check and verify. I’ve written up my issues with most major news coverage of AI water below. You don’t have to take my word for it, you can look at each one and see if I’m right or wrong for yourself.

The Georgia data center is only using ~2% of the county’s water. For comparison, a pharmaceutical manufacturing plant is using ~4% of the county’s water. A construction plant for Rivian cars is using about the same amount of water as Meta’s data center. The data center is functioning like any other normal industry in the county.

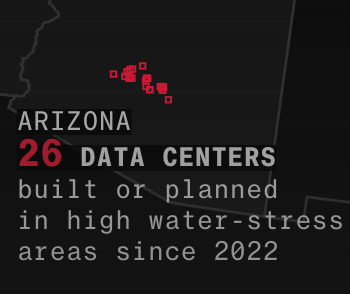

No matter where you look, whether it’s the place with the highest percentage of local water going to data centers (the Dalles, Oregon) or the place with the most water in total going to data centers (Loudoun County, Virginia) or the place with the highest water stress where lots of new data centers are being built (Maricopa County, Arizona), data centers are not negatively impacting local’s freshwater access at all, because they are behaving like any normal private industry. You can follow each link in the parentheses for a breakdown of how that county uses water and how data centers affect them.

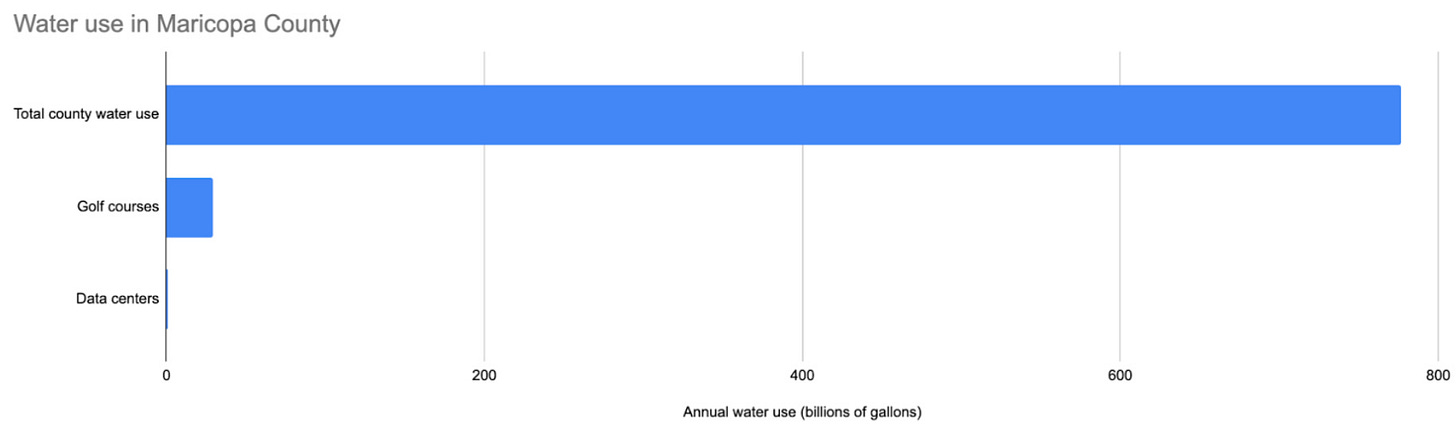

The only difference is that data centers contribute way way way more tax revenue per unit of water used than most other industries. Take Maricopa County in Arizona. The county is home to Phoenix, and is in a desert where water is pumped in from elsewhere. It’s also one of the places in the country where the most new data centers are being built.

Circle of Blue, a nonprofit research organization that seems generally trusted, estimates that data centers in Maricopa County will use 905 million gallons of water in 2025. For context, Maricopa County golf courses use 29 billion gallons of water each year. In total, the county uses 2.13 billion gallons of water every day, or 777 billion gallons every year. Data centers make up 0.12% of the county’s water use. Golf courses make up 3.8%.

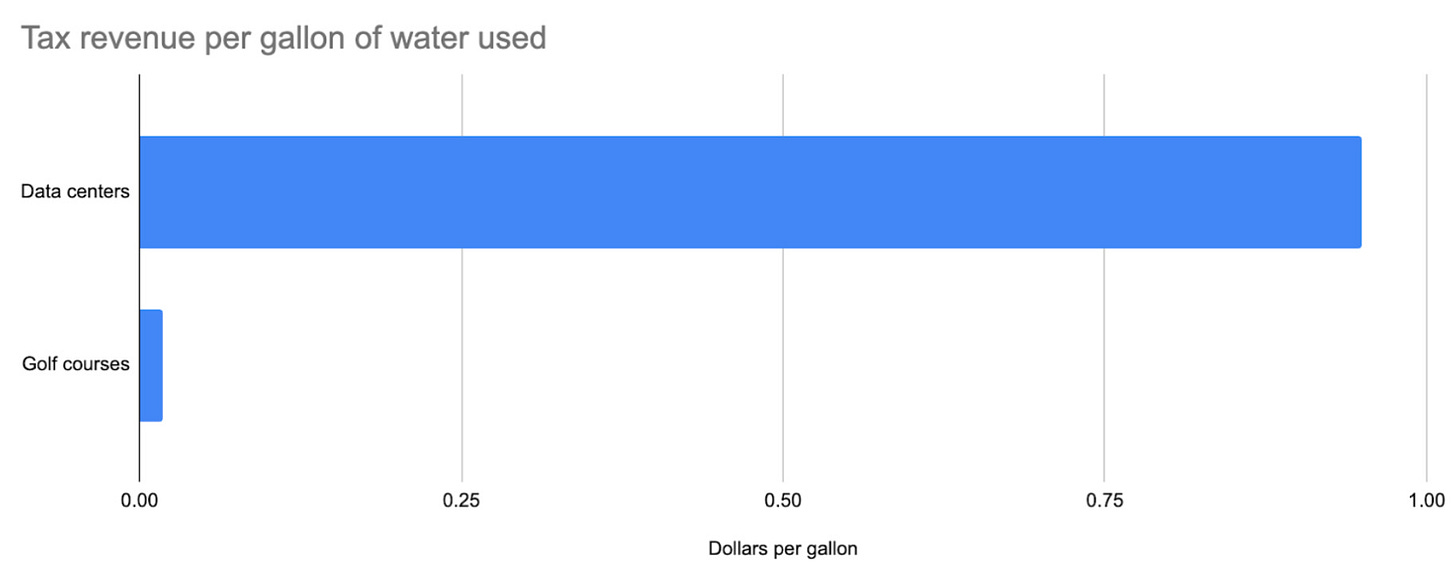

Data centers are so much more efficient with their water that they generate 50x as much tax revenue per unit of water used than golf courses in the county:

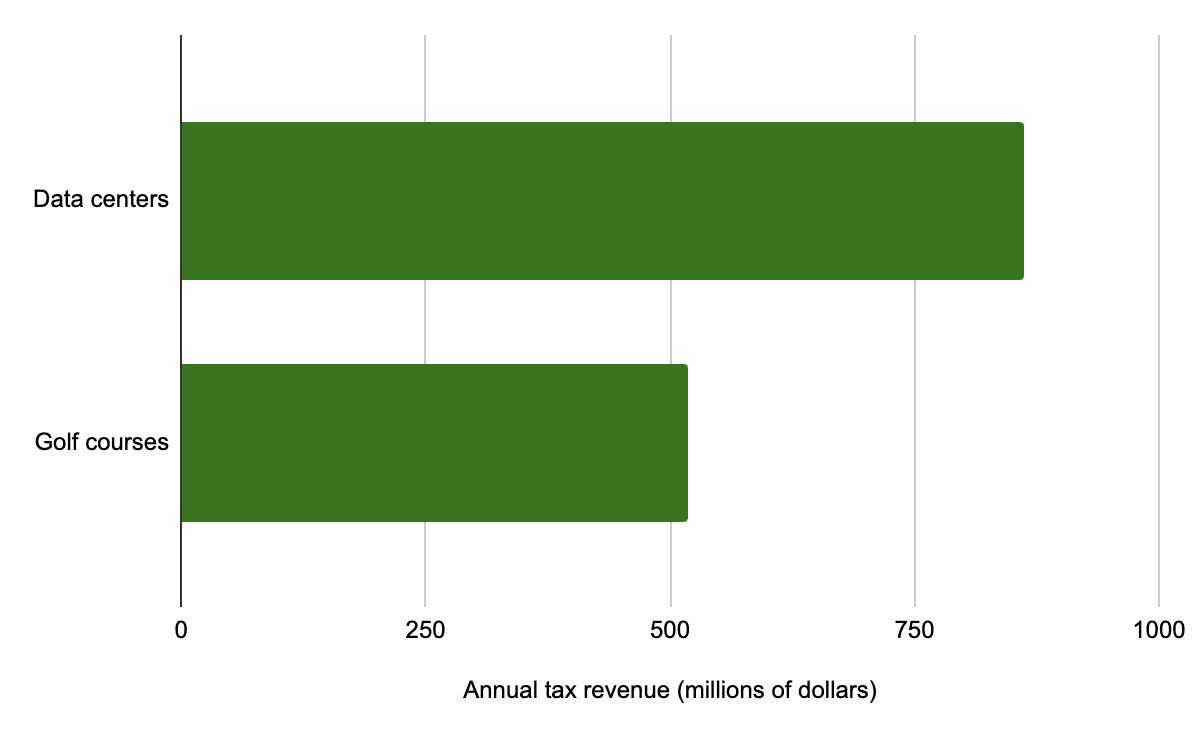

So even though data centers are using 30x less water than golf courses, they bring in more total tax revenue:2

In low water scarcity areas, data centers can actually benefit water access, because there water isn’t zero sum. More people buying water doesn’t lead to higher prices, it gives the utility more money to spend on drawing more water and improve infrastructure. It’s the same reason grocery prices don’t go up when more people move to a town. More people shop at the grocery store, which allows the grocery store to invest more in getting food, and they make a profit they can use to upgrade other services, so on net more people buying from a store often makes food prices fall, not rise. Studies have found that utilities pumping more water, on average, causes prices to fall, not rise.

In high water scarcity areas, city and state leaders have already thought a lot about water management. They can regulate data centers the same ways they regulate any other industries. Here water is more zero sum, but data centers just end up raising the cost of water for other private businesses, not for homes. Data centers are subject to the economics of water in high scarcity areas, and often rely more on air cooling rather than water cooling because the ratio of electric costs to water costs is lower.

This seems fine if we think of data centers as any other industry. Lots of industries in America use water. AI is using a tiny fraction compared to most, and generating way, way more revenue per gallon of water consumed than most. Where water is scarce, AI data centers should be able to bid against other commercial and industrial businesses for it. So far, I haven’t seen any arguments against building data centers in high water stress areas that aren’t basically saying “we shouldn’t have any industries at all in places with high water stress” which seems wrong. People still choose to live in places like Phoenix and expect to have strong local governments that need a big tax base to function well. If you’re against industry in high water stress areas period, you need to be against people living in Phoenix in the first place, which means their water bills should probably rise anyway.

There are many cases of data centers being built, providing lots of tax revenue for the town and water utility, and the locals benefiting from improved water systems. Critics often read this as “buying off” local communities, but there are many instances where these water upgrades just would not have happened otherwise. It’s hard not to see it as a net improvement for the community. If you believe it’s possible for large companies using water to just make reasonable deals with local governments to mutually benefit, these all look like positive-sum trades for everyone involved.

Here are specific examples:

The Dalles, Oregon - Fees paid by Google fund essential upgrades to water system.

Council Bluffs, Iowa - Google pays for expanded water treatment plant.

Quincy, Washington - Quincy and Microsoft built the Quincy Water Reuse Utility (QWRU) to recycle cooling water, reducing reliance on local potable groundwater; Microsoft contributed major funding (about $31 million) and guaranteed project financing via loans/bonds repaid through rates. These improvements increase regional water resilience beyond the data center itself.

Goodyear, Arizona - In siting its data centers, Microsoft agreed to invest roughly $40–42 million to expand the city’s wastewater capacity—utility infrastructure the city highlights as part of the development agreement and that increases system capacity for the community.

Umatilla/Hermiston, Oregon - Working with local leaders, AWS helped stand up pipelines and practices to reuse data-center cooling water for agriculture, returning up to ~96% of cooling water to local farmers at no charge.

I could go on like this for a while. Maybe you think every one of these is some trick by big tech to buy off communities, but all I’m seeing here is an improvement in local water systems without any examples of equivalent harm elsewhere

What about water pollution?

AI data centers are not a notable source of water quality pollution in their host communities. Their cooling water is typically kept in closed loops, any periodic blowdown is routed to a sanitary sewer for treatment or discharged under numeric permit limits, and an increasing share of facilities use highly treated recycled water that would otherwise be released by wastewater plants. By contrast, the largest water quality problems in the United States come from sectors like agriculture and construction.

The EPA’s national assessments repeatedly identify agriculture as the leading source of impairment for rivers and streams due to nutrient and sediment runoff, with continued nitrogen and phosphorus problems that affect drinking water and coastal ecosystems. Construction activity is also a well documented source of sediment discharges if not controlled. Data centers are not flagged by EPA in these national problem lists, and they do not handle the kinds of process chemicals or waste streams that typify the industrial categories with effluent guidelines.

This makes sense when you think about it. Data centers are just big computers. Water just runs through them to cool them, in the same way your laptop needs to be cooled by a fan. Why would using water to cool a big computer significantly pollute the water? You want the water interfering with the physical material of the big computer as little as possible.

How should local communities think about new data centers being built near them?

Data centers have an impact on local water systems, just like any other private industry. They shouldn’t just randomly be built anywhere. Local communities should consider the costs and benefits. But in doing this, they need to consider the actual amounts of water data centers will use compared to other normal industries, not compared to individual lifestyles. Many data centers use as much water as small to medium-sized beer breweries.

Obviously, questions about electricity or pollution are real and should be considered separately, but at least in terms of water, I can’t find a single example where data center operations have harmed local water access in any way, many places where they’ve benefited local water access, and a universal pattern of huge tax revenues.

Personal

I think a lot of people don’t realize how much water we each use every day. Altogether, the average person’s daily water footprint is 422 gallons, or 1600 liters. This is mostly from agriculture to grow our food, manufacturing products we use, and generating electricity. Only a small fraction is the water we use in our homes.

Our best current data on AI prompts’ water use from a thorough study by Google, which says that each prompt might only use ~2 mL of water if you include the water used in the data center as well as the offsite water used to generate the electricity.

This means that every single day, the average American uses enough water for 800,000 chatbot prompts. Each dot in this image represents one prompt’s worth of water. All the dots together represent how much water you use in one day in your everyday life (you’ll have to really zoom in to see them, each of those rectangles is 10,000 dots):

However, that 2 mL of water is mostly the water used in the normal power plants the data center draws from. The prompt itself only uses about 0.3 mL, so if you’re mainly worried about the water data centers use per prompt, you use about 300,000 times as much every day in your normal life. That’s the same water your local power plant uses to generate a watt-hour of energy, enough to use your laptop for about 2 minutes. So every hour that you use your laptop, you’re using up 30 chatbot prompt’s worth of water in a nearby power plant.

Have you ever worried about how much water things you did online used before AI? Probably not, because data centers use barely any water compared to most other things we do. Even manufacturing most regular objects requires lots of water. Here’s a list of common objects you might own, and how many chatbot prompt’s worth of water they used to make (all from this list, and using the onsite + offsite water value):

Leather Shoes - 4,000,000 prompts’ worth of water

Smartphone - 6,400,000 prompts

Jeans - 5,400,000 prompts

T-shirt - 1,300,000 prompts

A single piece of paper - 2550 prompts

A 400 page book - 1,000,000 prompts

If you want to send 2500 ChatGPT prompts and feel bad about it, you can simply not buy a single additional piece of paper. If you want to save a lifetime supply’s worth of chatbot prompts, just don’t buy a single additional pair of jeans.

Because generating electricity in America often involves water, anything that you do that uses electricity often also uses water. The average water used per kWh of electricity in America is 4.35 L/kWh, according to the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory. This has a few weird assumptions (explained here), so to be conservative I’ll divide it in half to 2 L/kWh. This means that every kWh of electricity you use evaporates the same amount of water as 1000 chatbot prompts (including both onsite + offsite water cost). Conveniently, 1 prompt’s water per Watt-hour.

Here are some common ways you might use electricity, and how many AI prompts’ worth of water the electricity used took to generate:

Playing a PS5 for an hour - 200 prompts’ worth of water

Using a laptop for an hour - 50 prompts’ worth of water

An LED light bulb on for an hour - 6 prompts

A digital clock for an hour - 1 prompt

Heating a kettle of water - 125 prompts’ worth of water (the kettle itself has enough water for ~500 prompts)

Heating a bath of warm water - 5000 prompts (the bathtub itself has enough water for 80,000 prompts)

If you want to reduce your water footprint, avoiding AI will never make a dent. These numbers are so incredibly small it’s hard to find things to compare them to. If you send 10,000 chatbot prompts per year, the water used in AI data centers themselves adds up to 1/300,000th of your total water footprint. If your annual water footprint were a mile, 10,000 chatbot prompts would be 0.2 inches.

Using AI can save way more water than is used in data centers

None of what I’m going to list here is generative AI like ChatGPT, but other machine learning tools have been heavily benefited by spillover effects from the general economic success of generative AI tools. These tools include things like computer vision systems for manufacturing quality control, predictive maintenance algorithms for industrial equipment, recommendation engines for e-commerce, fraud detection systems for financial services, and optimization algorithms for logistics and supply chains. While these applications have existed for years, the massive investment flowing into AI infrastructure (data centers, chip manufacturing, training talent) has made them cheaper, faster, and more accessible to deploy at scale.

AI is a way to get a machine to build its own soup of internal heuristics for how to handle complex situations. This soup of heuristics both succeeds and fails in surprising ways. We don’t design the heuristics themselves, and don’t even know what they are or how they work, in the same way we don’t know how a lot of the heuristics in our own brains work. There are a lot of situations where deploying this type of machine can help us optimize water use, because there are lots of places in America and around the world where huge amounts of water is wasted. Almost 20% of U.S. drinking water is lost to leaking pipes before reaching consumers.

AI leak detection saves 3 billion gallons of water over a few years in New Jersey.

AI detecting a single leak in a local suburb saved 350,000 gallons of water per day, saving a municipality $213,000 per year.

Another leak detection company saves 25,000,000 gallons of water per year.

A single AI-based irrigation optimization tool saved South American farmers 19 billion gallons of water over 2 years. This is 2 times as much water as all American AI data centers used over the same period.

This was the result of a few minutes of Googling. I could go on way longer with more examples of ways simple AI tools are saving towns huge amounts of water.

It’s okay to use water on a digital product

Many people’s background aversion to using water on data centers is that it’s a physical resource being spent on a digital product. Shouldn’t we only spend physical goods on other physical goods?

We already use a lot of water on the internet, and digital goods in general. Most of the ways we generate electricity uses a lot of water, so most of the time, when you’re using a computer, TV, or phone, you’re also using water. Internet data centers have always relied on water cooling, so we were always using water to access and share digital information.

Information is valuable. The real value of a book is almost entirely in the words it contains, not the physical quantity of ink and paper that make it up. We think it’s valuable to spend lots and lots of physical resources each year making books. Books and newspapers use 153 billion gallons of water annually. This is almost entirely in the service of delivering information. If it’s okay to spend water on creating and distributing books, it’s okay to spend water on other sources of valuable information. The water used to deliver digital information is orders of magnitude lower than physical books.

You might object that AI does not deliver anything like the value of books. My point isn’t to make a claim about how much valuable information AI provides, only that it isn’t inherently bad to spend a physical resource to deliver information. Ultimately if you believe AI is entirely valueless, than any water used on it is wasted regardless of whether AI’s output is physical or digital. But the fact that it’s digital on its own shouldn’t factor into whether you think it’s valuable or not.

The social value or harm of a tool isn’t the final word on how harmful it is to the environment

A very common point that comes up in conversations about AI and water use is that no matter how little water AI uses, AI is either useless or actively harmful, so all that water is being used on something bad. This makes it inherently worse than using any large amounts of water on good things. For example, when I share these stats from before:

Here’s a list of common objects you might own, and how many chatbot prompt’s worth of water they used to make (all from this list, and using the onsite + offsite water value):

Leather Shoes - 4,000,000 prompts’ worth of water

Smartphone - 6,400,000 prompts

Jeans - 5,400,000 prompts

T-shirt - 1,300,000 prompts

A single piece of paper - 2550 prompts

A 400 page book - 1,000,000 prompts

I often get the response that all of these things have social value, whereas AI has no value, so AI is worse for water than all these things, even though it’s using tiny tiny tiny amounts of water compared to each.

It seems like some people measure how wasteful something is with water is by a simple (Value to society / Water) equation where no matter how tiny something’s water use is, if it’s negative value, it’s always worse than something okay with huge water use.

This doesn’t make sense as a way of thinking about conserving water, for the same reason that it’s not a good way of thinking about saving money. If I were doing a fun activity that cost $40,000, and something useless or bad that cost $0.01, even though the $0.01 thing was bad, cutting it just would never ever be as promising or urgent as finding ways to reduce the cost of the $40,000 thing, or to just go without it.

Driving somewhere I want to be is much worse for the environment than riding a bike in the wrong direction. I agree that we need to factor in the value somehow, but it can’t just be “Anything socially bad is always worse for the environment than anything socially good.” AI water is often hundreds of thousands of times as small as many other ways we use water.

Talking about the social harm of a tool and adding “And it uses a few drops of water!” basically always dilutes the point you’re trying to make. I’m not exactly consistently pro AI. There’s a lot I’m worried about. But I find it distasteful when people effectively say “This far-right authoritarian government is using powerful AI systems to surveil people!… and also, every time they use it, a few drops of water are evaporated!” This just so obviously dilutes and trivializes the much more important point that I’d really rather it not be brought up. Manufacturing a gun uses at minimum 10,000 times as much water as an AI prompt in a data center, but if authoritarians are bearing down on people, I’m not going to add “And it cost a glass of water each to make their guns!'“

There’s a trade-off between water and energy for data center cooling systems. For the climate, water’s often preferable

Data centers don’t have to use water for cooling, they can also circulate cold air. They do this much more often when they’re built in deserts, because water’s more expensive and solar power’s cheaper and more abundant. As with any industry, they respond to the costs of goods and adjust how they use them accordingly.

But replacing water with air cooling systems means a lot more energy is used on cooling. Circulating cool air is more energy intensive than circulating water. Because water has much higher heat capacity and thermal conductivity than air, it can absorb and transfer heat more efficiently. Air cooling (especially in hot climates) requires stronger fans, chillers, compressors, and mechanical systems to push cooled air throughout the facility.

One study found that replacing air cooling with liquid cooling reduces a data center’s total power usage by 10%. This is a big deal, because electricity demand is a much more serious problem for data centers. Using 10% less energy also means roughly 10% less CO2 emissions. If water usage isn’t an issue, it seems like the main effect of water cooling is preventing a significant amount of CO2 emissions and electricity demand.

What about all those news stories about AI harming local water access?

Every popular article about how AI’s water use is bad for the environment in the last year has had a wildly misleading framing

The Economic Times: Texans are showering less because of AI

Take this one from the Economic Times, it circulated a lot:

The article clarifies that this is 463 million gallons of water spread over 2 years, or 640,000 gallons of water per day. Texas consumes 13 billion gallons of waters per day. So all data centers added 0.005% to Texas’s water demands.

0.005% of Texas’s population is 1,600. Imagine a headline that said “1,600 people moved to Texas. Now, residents are being asked to take shorter showers.”

Many iterations of the same article appeared:

San Antonio data centers guzzled 463 million gallons of water as area faced drought

Data Centers in Texas Used 463 Million Gallons of Water, Residents Told to Take Shorter Showers

One article corrected for the much larger uptick of data centers in 2025:

50 billion gallons per year is a lot more! That’s more like 1.1% of Texas’s water use. Nowhere in this article does it share that proportion. It seems pretty normal for a state as large as Texas to have a 1% fluctuation in its water demand.

The New York Times: Data centers are guzzling up water and preventing home building

From the New York Times:

The subtitle says: “In the race to develop artificial intelligence, tech giants are building data centers that guzzle up water. That has led to problems for people who live nearby.”

Reading it, you would have to assume that the main data center in the story is guzzling up the local water in the way other data centers use water.

In the article, residents describe how their wells dried up because residue from the construction of the data center added sediment to the local water system. The data center had not been turned on yet. Water was not being used to cool the chips. This was a construction problem that could have happened with any large building. It had nothing to do with the data center draining the water to cool its chips. The data center was not even built to draw groundwater at all, it relies on the local municipal water system.

The residents were clearly wronged by Meta here and deserve compensation. But this is not an example of a data center’s water demand harming a local population. While the article itself is relatively clear on this, the subtitle says otherwise!

The rest of the article is also full of statistics that seem somewhat misleading when you look at them closely.

Water troubles similar to Newton County’s are also playing out in other data center hot spots, including Texas, Arizona, Louisiana and the United Arab Emirates. Around Phoenix, some homebuilders have paused construction because of droughts exacerbated by data centers.

The term “exacerbated” is doing a lot of work here. If there is a drought happening, and a data center is using literally any water, then in some very technical sense that data center is “exacerbating” the drought. But in no single one of these cases did data centers seem to actually raise the local cost of water at all. We already saw in Phoenix that data centers were only using 0.12% of the county water. It would be odd if that was what caused home builders to pause.

The article goes on with some ominous predictions about Georgia’s water use around the data center, but so far residents have not seen their water bills rise at all. We’re good at water economics! You wouldn’t know that at all from reading this article.

I think the main story being an issue with construction, but the title associating it with some issue specific to data centers, seems pretty similar to a news story reporting on loud sounds from construction of a building that happens to be a bank, and the title saying “Many banks are known for their incredible noise pollution. Some residents found out the hard way.” This would leave you with an incorrect understanding of banks.

Contra the subtitle, data centers “guzzling up water” in the sense of “using the water for cooling” has not led to any problems, anywhere, for the people who live nearby. The subtitle is a lie.

CNET’s long very vague report on AI and water

This same story was later referenced by a long article on AI water use at CNET, here with a wildly misleading framing:

The developer, 1778 Rich Pike, is hoping to build a 34-building data center campus on 1,000 acres that spans Clifton and Covington townships, according to Ejk and local reports. That 1,000 acres includes two watersheds, the Lehigh River and the Roaring Brook, Ejk says, adding that the developer’s attorney has said each building would have its own well to supply the water neededEverybody in Clifton is on a well, so the concern was the drain of their water aquifers, because if there’s that kind of demand for 34 more wells, you’re going to drain everybody’s wells,” Ejk says. “And then what do they do?”

Ejk, a retired school principal and former Clifton Township supervisor, says her top concerns regarding the data center campus include environmental factors, impacts on water quality or water depletion in the area, and negative effects on the residents who live there.

Her fears are in line with what others who live near data centers have reported experiencing. According to a New York Times article in July, after construction kicked off on a Meta data center in Social Circle, Georgia, neighbors said wells began to dry up, disrupting their water source.

There’s no mention anywhere in the article that the data center in Georgia was not using the well water for normal operations.

Bloomberg: AI is draining water from areas that need it most

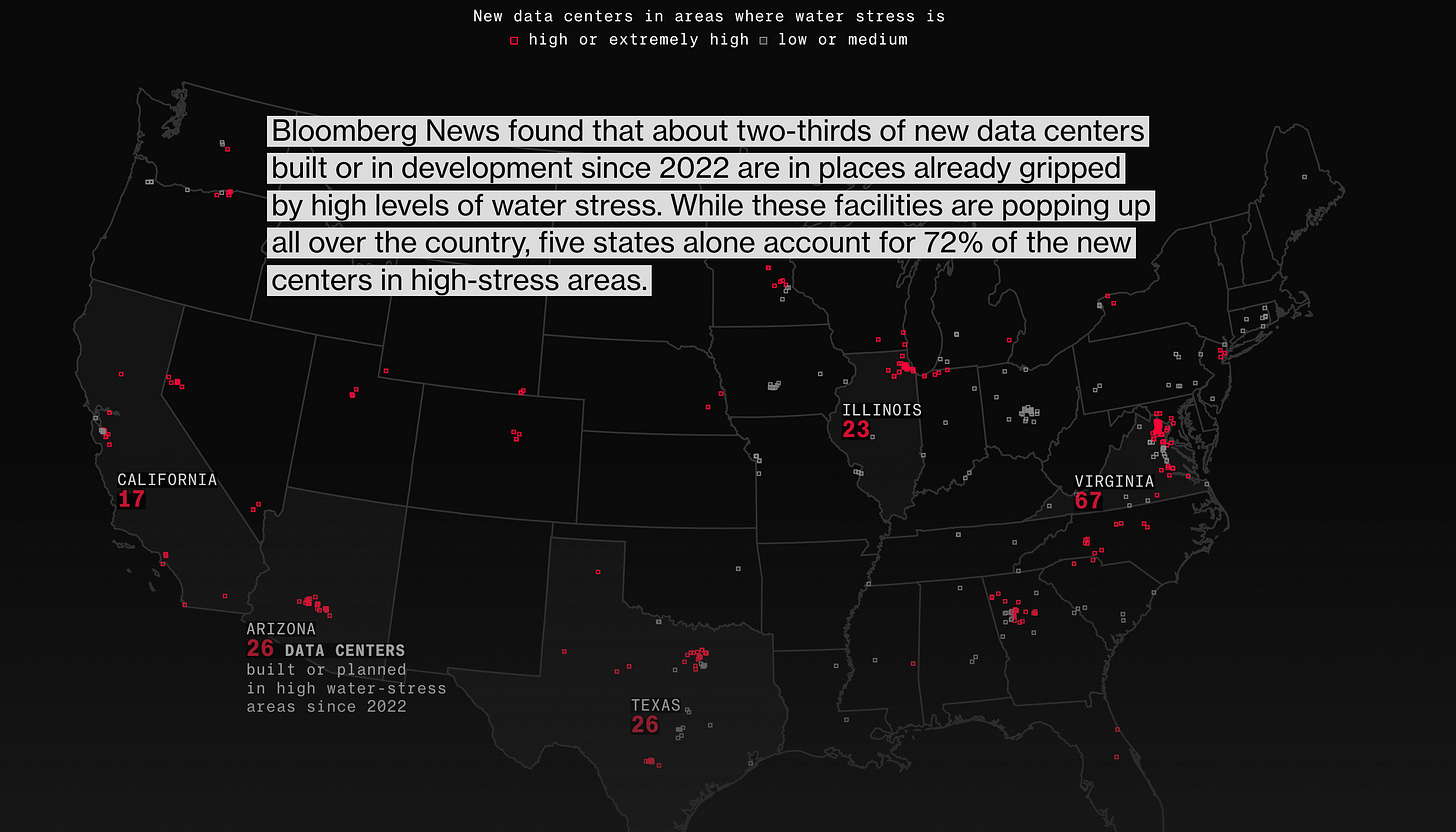

Here’s a popular Bloomberg story from May. It shows this graphic:

Red dots indicate data centers built in areas with higher or extremely high water stress. My first thought as someone who lives in Washington DC was “Sorry, what?”

Northern Virginia is a high water stress area?

I cannot find any information online about Northern Virginia being a high water stress area. It seems to be considered low to medium. Correct me if I’m wrong. Best I could do was this quote from the Financial Times:

Virginia has suffered several record breaking dry-spells in recent years, as well as a “high impact” drought in 2023, according to the U.S. National Integrated Drought Information System. Much of the state, including the northern area where the four counties are located, is suffering from abnormally dry conditions, according to the U.S. Drought Monitor. But following recent rain, the Virginia Department of Environmental Quality on Friday lifted drought advisories across much of the state, though drought warnings and watches are still in effect for some regions.

Back to the map. There were some numbers shared in a related article by one of the same authors. But readers were left without a sense of proportion of what percentage of our water all these data centers are using.

AI’s total consumptive water use is equal to the water consumption of the lifestyles of everyone in Paterson, New Jersey. This graphic is effectively spreading the water costs of the population of Paterson across the whole country, and drawing a lot of scary red dots. The dots are each where a relatively tiny, tiny amount of water is being used, and they’re only red where the regions are struggling with water. This could be done with anything that uses water at all and doesn’t give you any useful information about how much of a problem they are for the region’s water access.

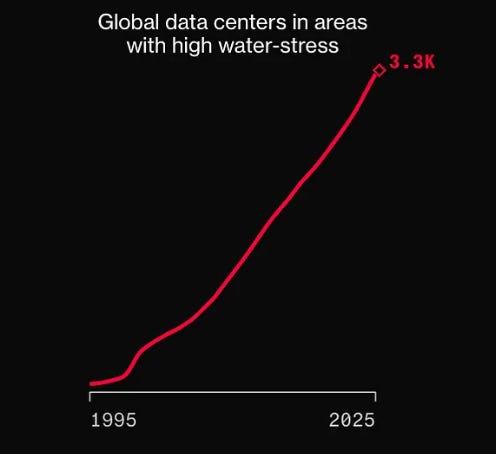

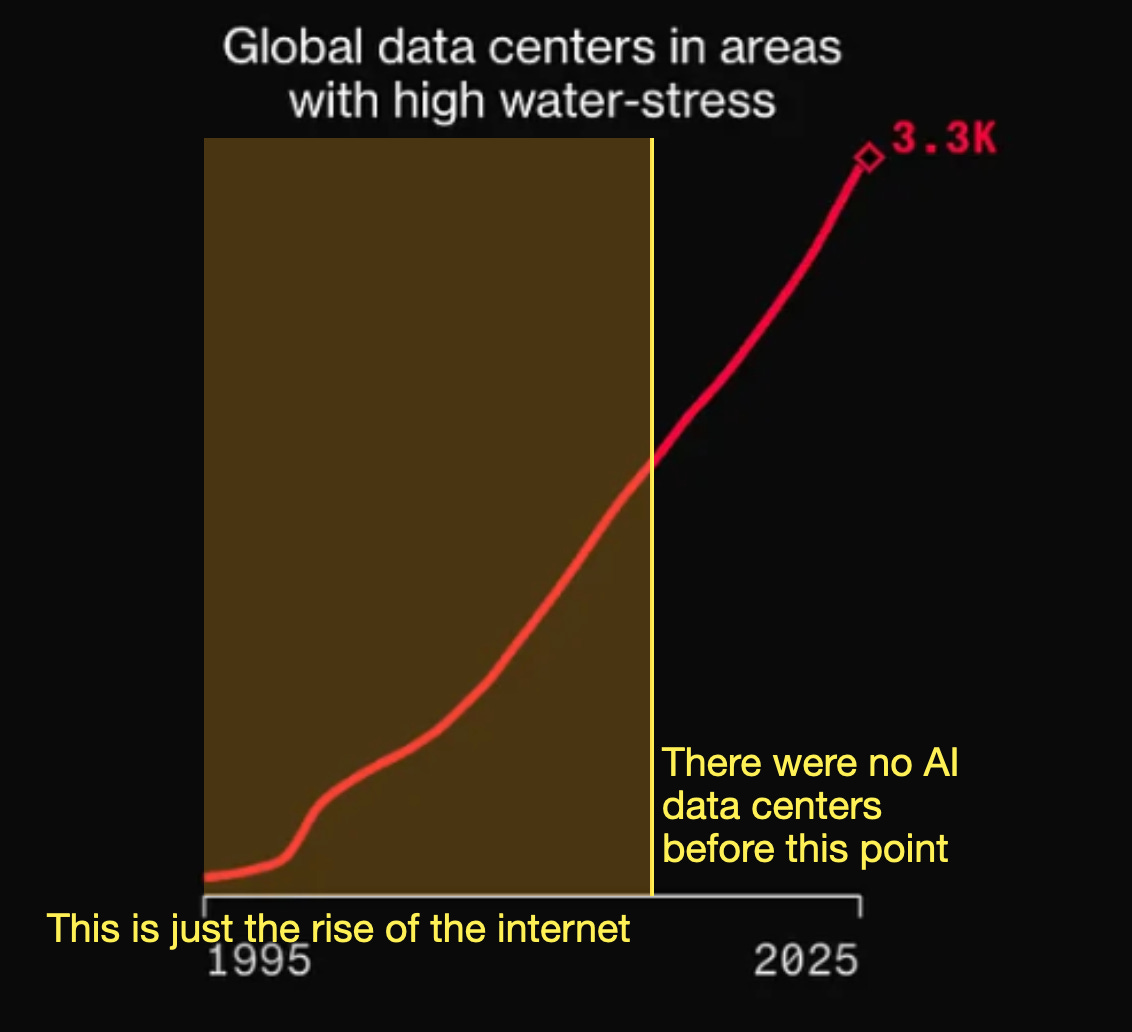

Even the title chart can send the wrong message.

I think for a lot of people, stories about AI are their first time hearing about data centers. But the vast majority of data centers exist to support the internet in general, not AI.

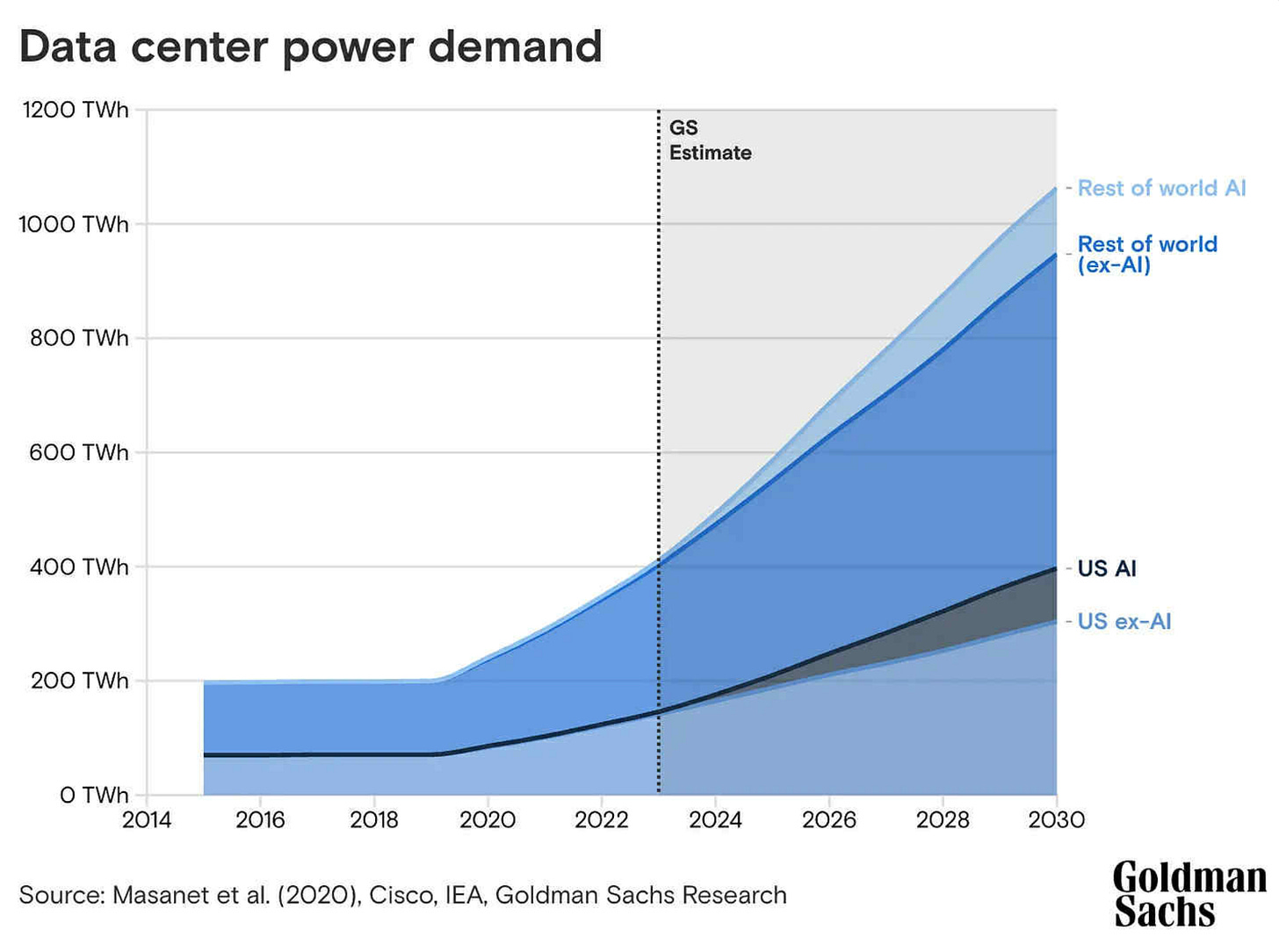

Simply showing the number of data centers doesn’t show the impact of AI specifically, or how much power data centers are drawing. Power roughly correlates with water, because the more energy is used in data center computers, the more they need to be cooled, and the more water is needed to do that. Here’s a graph showing the power demand of all data centers, and how much of that demand AI makes up.

Obviously there’s been a big uptick on power draw since 2019, but AI is still a small fraction of total data center power draw. I think Goldman Sachs underestimated AI’s power draw here, experts think it’s more like ~15% of total power used in data centers, but it’s important to understand that the vast majority of that original scary red data center graph isn’t AI specifically.

AI is going to be large part of the very large data center buildout that’s currently underway, but it’s important to understand that up until this point most of those data centers on the graph were just the buildout of the internet.

One more note, circling back again to Maricopa County.

The county is a gigantic city built in the middle of a desert. For as long as it’s existed, it’s been under high water stress. Everyone living there is aware of this. The entire region is (I say this approvingly) a monument to man’s arrogance.

The only reason anyone can live in Phoenix in the first place is that we have done lots of ridiculous massive projects to move huge amounts of water to the area from elsewhere.

This is an area where environmentalism and equity come apart. I’d like residents of Phoenix to have access to reliable water supplies, but I don’t think this the most environmentalist move. I think the most environmentalist move would probably be to encourage people to leave the Phoenix area in the first place and live somewhere that doesn’t need to spend over two times as much energy as the country on average pumping water. I have to bite the bullet here and say that between environmentalism and equity, I’d rather choose equity and not raise people’s water prices much, even though they’ve chosen to live in the middle of a desert.

It seems inconsistent to think that it’s wrong for environmentalist reasons to build data centers near Phoenix that increase the city’s water use by 0.1%, but it’s not wrong for Phoenix to exist in the first place. If it’s bad for the environment to build data centers in the area at all, Phoenix’s low water bills themselves seem definitionally bad for the environment too. I think you can be on team “Keep Phoenix’s water bills low, and build data centers there” or team “Neither the data centers nor Phoenix should be built there, we need to raise residents’ water bills to reflect this fact” but those are the only options. I’m on team build the data centers and help out the residents of Phoenix.

More Perfect Union

More Perfect Union is one of the single largest sources of misleading ideas about data center water usage anywhere. They very regularly put out wildly misleading videos and headlines. There are so many that I’ve written a long separate post on them here. They are maybe the single most deceptive media organizations in the conversation relative to their reach.

5 common misleading ways of reporting AI water usage statistics

Comparing AI to households without clarifying how small a part of our individual water footprint our households are

Many articles choose to report AI’s water use this way:

“AI is now using as much as (large number) of homes.”

Take this quote from Newsweek:

In 2025, data centers across the state are projected to use 49 billion gallons of water, enough to supply millions of households, primarily for cooling massive banks of servers that power generative AI and cloud computing.

That sounds bad! The water to supply millions of homes sounds like a significant chunk of the total water used in America.

The vast majority (~93%) of our individual total consumption of freshwater resources does not happen in our homes, it happens in the production of the food we eat. Experts seem to disagree on exactly what percentage of our freshwater consumption happens in our homes, but it’s pretty small. Most estimates seem to land around 1%. So if you just look at the tiny tiny part of our water footprint that we use in our homes, data centers use a lot of those tiny amounts. But if you look at the average American’s total consumptive water footprint of ~1600 L/day, 49 billion gallons per year is about 300,000 people’s worth of water. That’s about 1% of the population of Texas. The entire data center industry (both for AI and the internet) using as much water as 1% of its population just doesn’t seem as shocking.

Referencing the “hidden, true water costs” that AI companies are not telling you, without sharing what those very easily accessible costs are

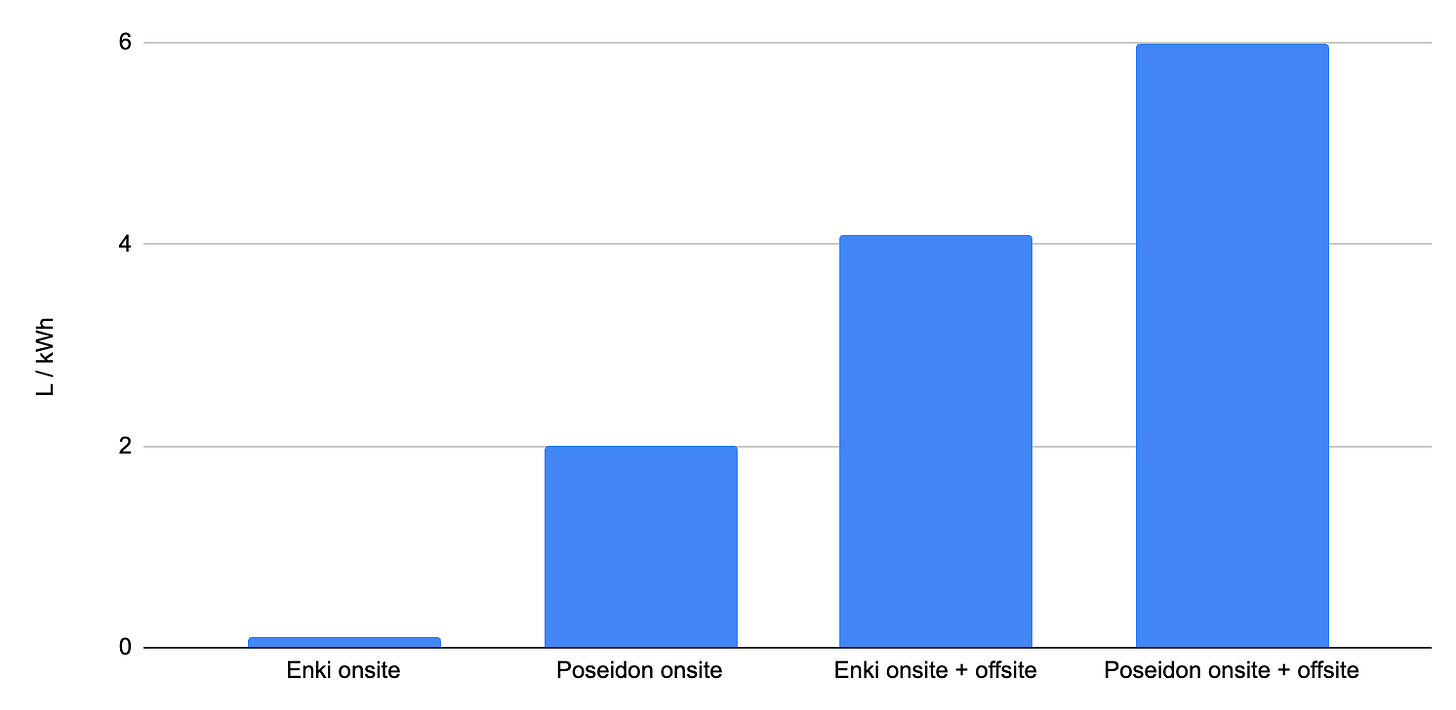

A move that I complained about in my last post is that a lot of articles will imply that AI companies are hiding the “true, real” water costs of data centers by only reporting the “onsite” water use (the water used by the data center) and not the “offsite” water use (the water used in nearby power plants to generate the electricity). Reporting both onsite and offsite water costs has become standard in reporting AI’s total water impact.

Many authors leave their readers hanging about what these “true costs” are. They’ll report a minuscule amount of water used in a data center, and it’s obvious to the reader that it’s too small to care about, but then the author will add “but the true cost is much higher” and leaves the reader hanging, to infer that the true cost might matter.

We actually have a pretty simple way of estimating what the additional water cost of offsite generation is. Data centers on average use 0.48 L of water to cool their systems for every kWh of energy they use, and the power plants that provide data centers energy average 4.52 L/kWh. So to get a rough estimate:

If you know the onsite water used in the data center, multiply it by 10.4 to get the onsite + offsite water.

If you know the onsite energy used, multiply it by 5.00 L/kWh to get the onsite + offsite water used.

Obviously scaling up a number by a factor of 10 is a lot, but it often still isn’t very much in absolute terms. Going from 5 drops for a prompt to 50 drops of water is a lot relatively, but in absolute terms it’s a change from 0.00004% of your daily water footprint to 0.0004%. Journalists should make these magnitudes clear instead of leaving their readers hanging.

This talking point can be doubly deceptive if you only look at the proportion

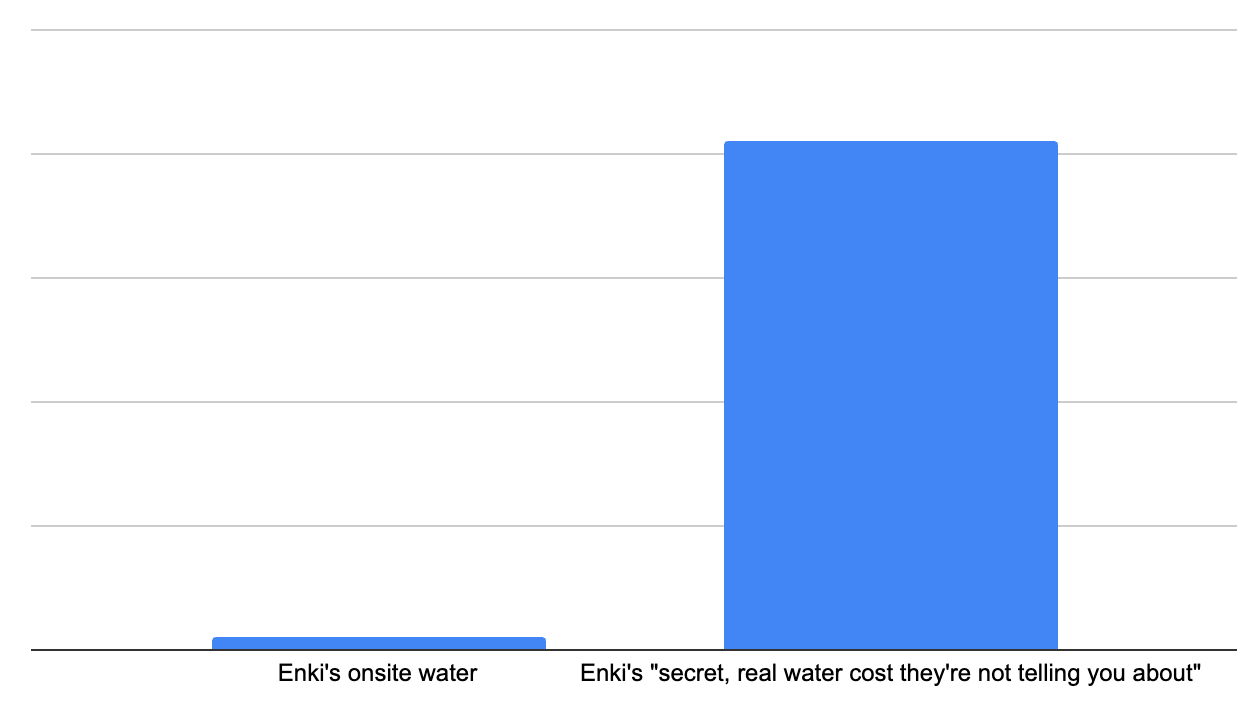

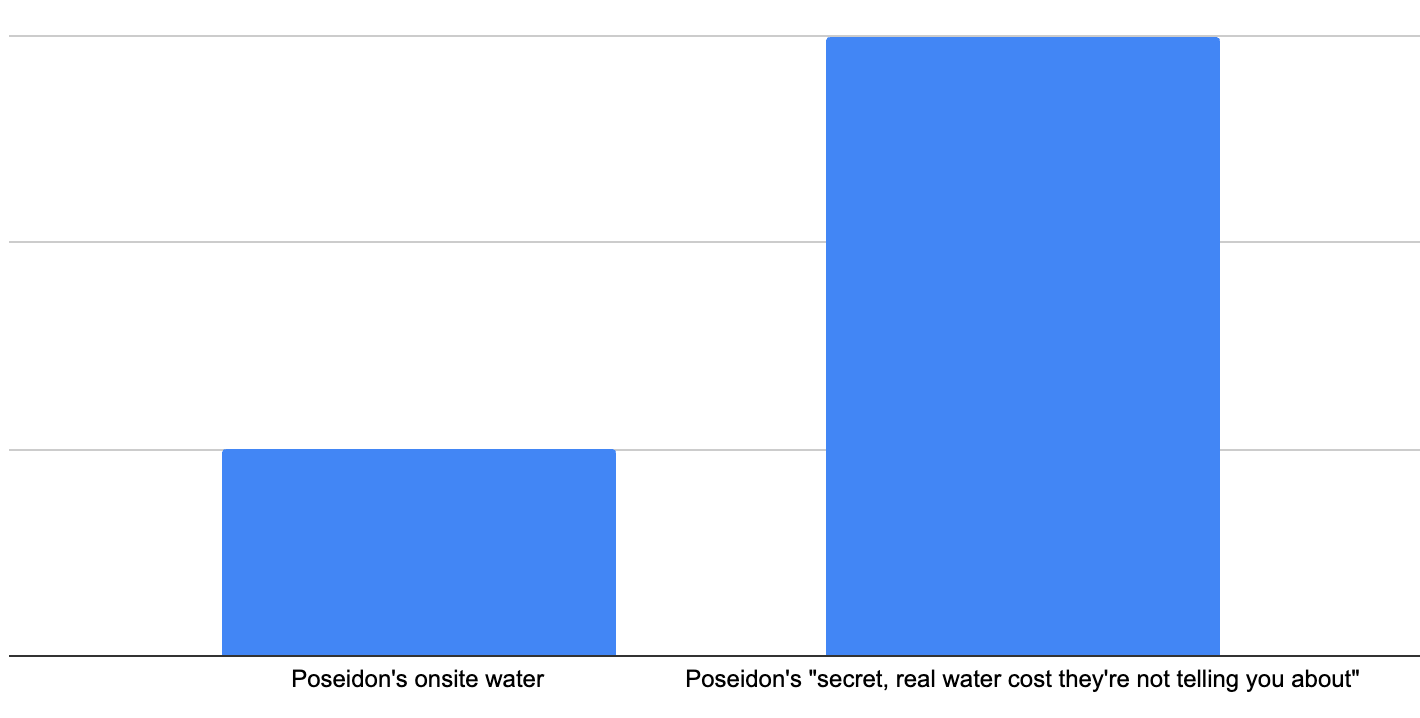

Let’s say there are 2 data centers in a town (I’ll call them Poseidon and Enki) drawing from the same power source. The local town’s electricity costs 4 L of water per kWh to generate.

The Poseidon data center is pretty wasteful with its cooling water. It spends 2 L of water on cooling for every kWh it uses on computing, way above the national average of 0.48L/kWh. So if you add the onsite and offsite water usage, Poseidon uses 6 L of water per kWh.

The Enki data center finds a trick to be way more efficient with its cooling water. It drops its water use down to 0.1L/kWh. Well below the national average. So if you add its onsite and offsite water usage, it uses 4.1 L per kWh without using any more energy.

Obviously, the Enki data center is much better for the local water supply.

Both data centers are asked by the town to release a report on how much water they’re using. They both choose to only report on the water they’re actually using in the data center itself.

Suddenly, a local newspaper shares an expose: both data centers are secretly using more water than they reported, but Enki’s secret, real water use is 41x its reported water costs.

While Poseidon’s is only 3x its reported water costs:

Here, Enki looks much more dishonest than Poseidon. If readers only saw this proportion, they would probably be left thinking that Enki is much worse for the local water supply. But this is wrong! Enki’s much better. The reason the proportions are so different is that Enki’s managed to make its use of water so efficient compared to the nearby power plant.

I think something like this often happens with data center water reporting.

When I wrote about a case of Google’s “secret, real water cost” actually not being very much water, a lot of people messaged me to say Google still looks really dishonest here, because the secret cost is 10x its stated water costs once you add the offsite costs. A way of reframing this is to say that Google’s made its AI models so energy efficient that they’re now only using 1/10th as much water in their data centers per kWh as the water required to generate that energy. This seems good! We should frame this as Google solidly optimizing its water use.

Take this quote from a recent article titled “Tech companies rarely reveal exactly how much water their data centers use, research shows”:

Sustainability reports offer a valuable glimpse into data center water use. But because the reports are voluntary, different companies report different statistics in ways that make them hard to combine or compare. Importantly, these disclosures do not consistently include the indirect water consumption from their electricity use, which the Lawrence Berkeley Lab estimated was 12 times greater than the direct use for cooling in 2023. Our estimates highlighting specific water consumption reports are all related to cooling.

The article should have mentioned that this means data centers have made their water use so efficient that basically the only water they’re using at all is in the nearby power plant, not in the data centers themselves. But framing it in the original way way make it look like the AI labs are hiding a massive secret cost from local communities, which I guess is a more exciting story.

Vague gestures at data centers “straining local water systems” or “exacerbating drought” without clarifying what the actual harms are

If you use literally any water in any area with a drought, you’re in some sense “straining the local water system” and “exacerbating the drought.” Both of these tell us basically nothing meaningful about how bad a data center is for a local water system. If an article doesn’t come with any clarification at all about what the actual expected harms are, I would be extremely wary of this language. In basically every example I can find where it’s used, the data centers are adding minuscule amounts of water demand to the point that they’re probably not changing the behavior of any individuals or businesses in the area.

Simply listing very large numbers without any comparisons to similar industries and processes

This is the great singular sin of bad climate communication. The second you see it, you should assume it’s misleading. Simply reporting “millions of gallons of water” without context gives you no information. The power our digital clocks draw use millions of gallons of water, but digital clocks aren’t causing a water crisis.

Take this example:

7.2 million gallons per year! Sounds like a ton. How much is that? About as much as a small craft brewery. How worried should local residents of a county be about water use if they found out a new craft brewery were opening nearby? Probably not nearly as much as this tweet is trying to get across. This data center would represent about 0.02% of nearby El Paso’s water usage.

Whenever you see an article cite a huge amount of water with no comparisons at all to anything to give you a proper sense of proportion, ask a chatbot to contextualize the number for you.

Take this excerpt from “Are data centers depleting the Southwest’s water and energy resources?”

Meta’s data centers, meanwhile, withdrew 1.3 billion gallons of water in 2021, 367 million of which were from areas with high or extremely high water stress. Total global water consumption from Meta’s data centers was over 635 million gallons, equivalent to about 6,697 U.S. households. It’s not clear how much of this water withdrawal occurs in the United States, although that’s where most of Meta’s data centers are located. Neither report reveals the specific water use of the company’s Arizona data center.

I’m going to rewrite this, but using my town of 16,000 people (Webster, Massachusetts) as a unit to measure Meta’s data center withdrawal instead of individual households. Webster’s utility delivers 1.4 million gallons of water per day to the citizens and businesses there (511 million gallons per year).

Meta’s data centers, meanwhile, withdrew as much water as 3 Massachusetts small towns in 2021. Two thirds of a single one of those small towns was in areas with high or extremely high water stress. Total global water consumption from Meta’s data centers was a little more than a single Massachusetts small town. It’s not clear how much of this water withdrawal occurs in the United States, although that’s where most of Meta’s data centers are located. Neither report reveals the specific water use of the company’s Arizona data center.

This all seems silly when you consider Meta’s one of the single largest internet companies.

Reporting the maximum upper bound for water a data center uses as the number it will actually use

Many articles about current or future AI data centers report how much water they use

When a data center is being built, the company needs to obtain water use permits from local authorities before construction. At this stage, they have to estimate their maximum possible water consumption under worst-case scenarios:

All cooling systems running at full capacity

Peak summer temperatures

Maximum IT load (every server rack filled and running)

Minimal efficiency from cooling systems

The permit needs to cover this theoretical maximum because regulators want to ensure the local water infrastructure can handle the demand and that there’s enough water supply for everyone. It’s easier to get a higher permit upfront than to come back later and request more, so data centers are incentivized to aim high.

Actual water usage is always significantly lower than what the permits allow, because they’re designed with the absolute worst conditions in mind. But many popular articles about how much water data centers use give the number on the water permit, not how much the data center actually uses.

Duff is the only city council member to vote no on a recently approved $800 million data center - rumored to be for Facebook - after discovering the facility would eventually use 1.75 million gallons of water every day for cooling their rows of servers once fully operational.

Further reading

The Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory’s report on data center energy and water use in 2024 is the most comprehensive document we have on AI and water right now.

Brian Potter’s recent piece on water and update on data center water use.

Hannah Ritchie has some recent great stuff on data centers and chatbots

Matt Yglesias’s piece on data centers and water

Friend of the blog SE Gyges has a great breakdown of the single most popular statistic about ChatGPT that’s also a lie: it uses a bottle of water per email.

More from me:

Top of page 3

I thank you for doing this, Andy, but IMO, few of these people are arguing in good faith.

I'm not saying they are "evil" or stooges. Just that Doom is their religion.

https://www.mattball.org/2023/05/doom-force-that-gives-life-meaning.html

This is the most grounded, data-driven take I’ve seen on AI and water use. The argument that AI is some outsized environmental villain when it comes to water just doesn’t hold up under scrutiny — especially when data centers are using a fraction of the water that golf courses or agriculture consume daily.

We should be critical of how tech impacts the environment, but let’s focus on the real issues (like electricity usage and e-waste), not the hyped-up distractions. Comparing AI water use to adding a few midsize towns across the U.S. really puts it in perspective.