All the ways I want the AI debate to be better

Ground truths, useful rules, ideas I'd like taken seriously, and a rant

This is a list of the ways I think conversations about AI could be better, split into four parts:

Ground truths everyone needs to agree on. These are the foundational ideas someone needs to accept for their opinions to be taken seriously. There are incorrect ideas circling around AI debates that need to be rejected before serious conversations can happen.

Useful rules for debates to make sure they don’t get stuck or confused.

Ideas I’d like taken seriously in any discussions about AI. Many reasonable people disagree with each, but each has enough serious people and arguments behind it that it deserves a seat at the table and shouldn’t be written off.

A rant about how tribal AI conversations have become.

I wrote this partly as an imagined instruction manual to my past self in my first year of college. I’d want past me to know what the most useful and exciting ideas are for thinking well about AI. In college I enjoyed reading long meandering blog posts way above their authors’ actual level of expertise, so I’m writing one of my own. This is why I’ve added long sections that explain Quine or authors writing about technological determinism. I’d want past me to know a lot about both.

Everything here is a one-off take so you can bounce around and only read what’s interesting to you. Some parts of this will be copied from earlier posts, especially my post on philosophy and AI.

Contents

Always include an “AI is capable/incapable” axis in addition to a “Pro” and “Anti” axis

Clarify when the complaint is that AI is empowering people too much

Clarify when AI is just a continuation of an existing tool or practice

Before people make big claims about what chatbots can and can’t do, they need to try using one

1: Ground truths everyone needs to agree on

These are the facts about AI that are so important and obvious that we should write off the opinions of the people who deny them. It’s understandable to be confused about them when you first learn about AI, but having lots of opportunities to learn and still confidently making these errors is a sign that you’re willfully ignorant and trying to throw off the conversation.

Chatbots aren’t “useless”

Everyone needs to acknowledge that chatbots are sometimes useful to people. I don’t mean they’re perfect or they never hallucinate or they’re always preferable to a human. I just mean they’re one tool among many that can in particular circumstances make your life better. YouTube and TikTok and Instagram and Minecraft are also “useful.” None of these are perfect, each has specific use cases and things they’re bad at. The same goes for chatbots.

This seems obvious. However, there are enough people with large audiences making sweeping hyperbolic claims that AI is completely useless that it’s worth clarifying.

A simple proof that chatbots aren’t useless

A few days ago I was reorganizing the physics videos on my website. I already had them sorted on my YouTube channel. Instead of typing the names of each video or copying them one by one into a new list, I just took a screenshot of my YouTube playlist, gave it to ChatGPT, and asked “Please make a bullet point list of each, capitalizing only the first letter of each title, and removing “ - IB physics” from the end of each. I have about 200 videos, so this saved me at minimum half an hour of meaningless work.

I shared this online and got a reply from another physics teacher:

If “useless” means “something that cannot produce useful results and save you time” then ChatGPT is proved conclusively to be not useless.

Ways AI has been useful to people

Here’s a list of posts about how people use AI:

If you read these and still think AI is useless, you have wildly high expectations for it that we don’t hold for any other technology. AI isn’t as good as having a personal smart human helper do anything I want, but it’s at least as useful as YouTube or Wikipedia or my cell phone’s camera. Each other tool also has lots of flaws and limitations, but also obvious places where it helps me.

It’s easy to criticize AI and find ways it can be harmful without calling it useless. It’s similar to cars. You can believe that cars are bad for society and create a lot of complex problems without believing cars are completely useless. Their usefulness is often the reason why the problems show up!

Other people are smart

Critics of chatbots sometimes talk as if most people aren’t smart. They’ll talk about how everyone using ChatGPT has been brainwashed into not noticing that it’s useless and can’t possibly provide value. A billion people use ChatGPT weekly. This is basically saying all of those billion people are too stupid to notice they’re using an app that produces gibberish, and never adds value to their lives.

You can think AI is bad for society without saying it’s completely useless to all the billion people using it. At some point this just shows a failure to respect the pluralism of other people’s tastes and goals for themselves.

I think TikTok is probably bad for society, but I understand that for a lot of people it’s provided a lot of subtle nuanced benefits you can only understand by using it and living in their specific social situations. It can teach you social cadences and give you glimpses into different lives and entertain you and help you keep up with popular jokes and memes. TikTok is useful for a lot of people, even if on net I think it’s bad. I know this because I’m pluralistic enough to defer to the large groups of people using it on whether it’s useful to them, even if I don’t get much value out of it.

People who aren’t using AI also often have great reasons to not use it. Domain experts can recognize where chatbots are too prone to hallucinations to help. I always assume these people know what’s up in their fields and can identify AI’s limitations. This is a great recent piece by a physicist on his negative experiences using AI for science and how it’s currently being overhyped in specific places. Again, it’s pretty easy to just assume most people are smart and can work out for themselves where AI is and isn’t useful to them. But assuming that every last AI user isn’t noticing that it’s not adding any value to their lives is deeply disrespectful to the judgment and values of an eighth of the world.

Tools to “replace thinking” sometimes help us think more deeply

Some people say AI is a “substitute for actual thinking.” There are a lot of serious examples of this, like students using chatbots to cheat. But some people take this farther and say that it’s always bad to “replace your thinking” with AI, even for mundane things like coming up with recipes or checking your writing for grammar issues or coding something simple for a website.

This specific criticism is too strong, because it applies to and condemns most useful technology and social practices.

Whitehead has a great simple quote I think of often:

Civilization advances by extending the number of important operations which we can perform without thinking of them.

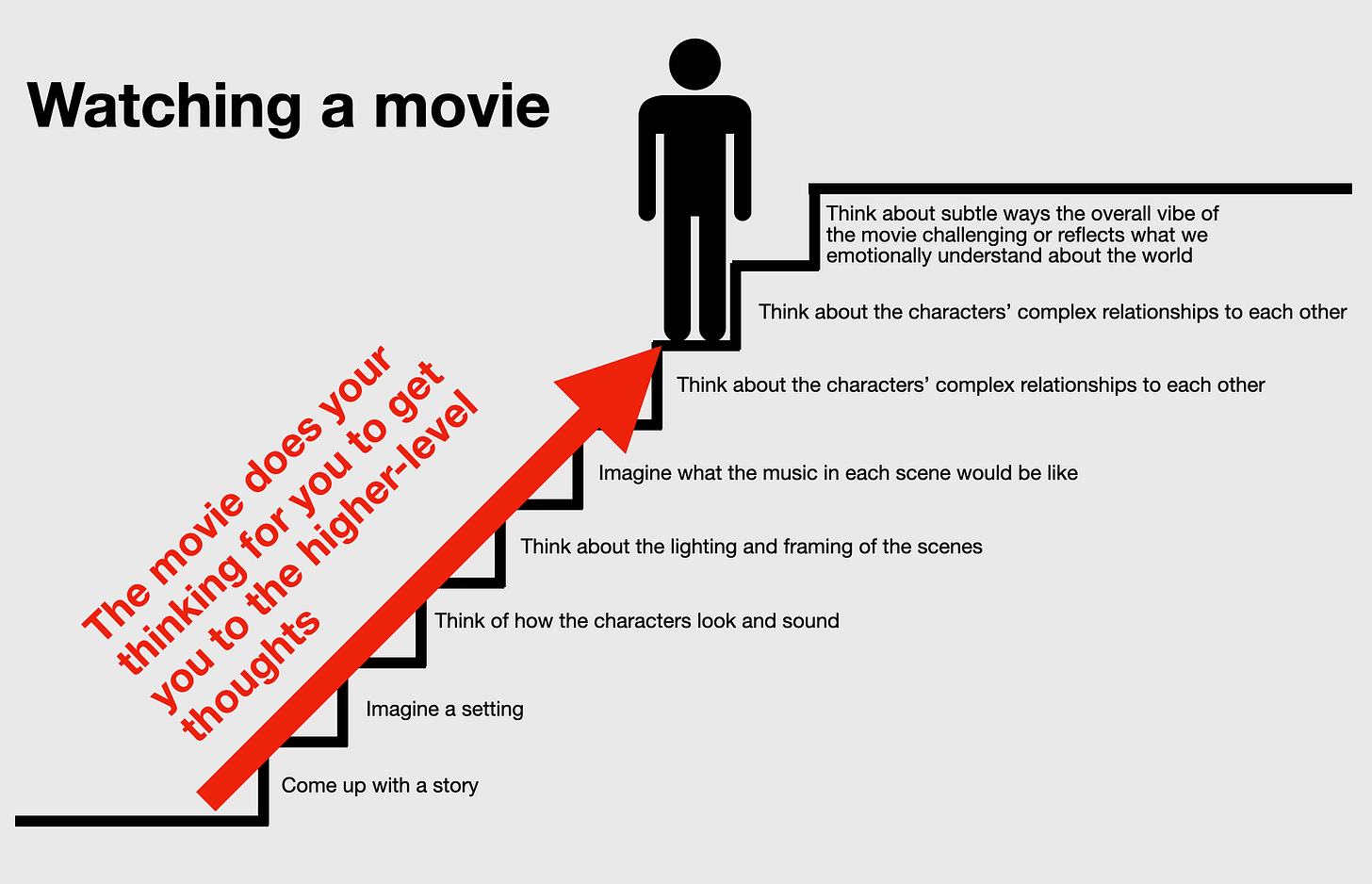

If I want food, I “replace my thinking” by Googling a recipe and making a shopping list based on the ingredients. Google Maps removes my need to think about how to navigate on a road trip. Any philosophy book removes my need to think hard enough to arrive at the idea from first principles. A movie removes my need to make up a story in my head. Each of these are in some ways “replacing my thinking” with a technological experience that does the thinking for me.

Each of these also frees me from monotony and lets me get to the higher level thinking I’d rather be doing.

Imagine that movies didn’t exist, but I still want the higher-level thoughts and experiences that come with them. I’d have to put in the work of imagining a movie in my head. To get to the higher level thoughts, I’d have to climb all these additional steps:

Now I have access to movies again. They “do my thinking for me” and allow me to jump to what I actually want: a more complex experience of characters, vibes, and general commentary and emotional intuitions about life.

What I find meaningful and good about life exists at these higher levels. AI tools are a way to replace simple monotonous thinking tasks that won’t make my life better, like doing simple back of the envelope calculations or finding recipes online or web design or summarizing difficult technical papers I don’t have time to read. This helps me get to where I actually want to be: in a place where I can do more during the day and leave more room for the experiences that make life worthwhile.

It’s good to use technology to “replace” this type of thinking. It’s one of the things technology’s for.

Some people replace more important experiences with AI. They form relationships with AI chatbots or use AI for serious therapy or summarize books that they’d get a lot more out of if they actual read. This is irresponsible and should receive some social pushback, but in my experience it’s not the way most people are using AI.

The line between glorified auto-complete (next-token prediction) and real intelligence is blurry

LLMs are trained to predict the next word (or more precisely, the next token, which may not be a full word) in a string of text. The feedback they receive during training compares their guesses to the actual next words.

A common criticism of LLMs is that they’re “just glorified auto-complete” because they’re trained to predict the next word. I think people who say this don’t understand that next-token prediction is just the part of the model that receives feedback about whether it’s getting the word right. It takes this feedback and sends it back through over 1 trillion parameters to adjust its intuitions, eventually detecting extremely subtle patterns to build what looks a lot like a model of the world. This and this video are great explanations of how this feedback happens and how an LLM might come to build a model of the world using that feedback.

Next-token prediction is similar to evolutionary natural selection. Both are simple algorithms with simple outputs. Next-token prediction says “This word is more likely to be correct, that one is less likely to be correct” and tells the trillions of parameters of the AI to adjust accordingly. Each parameter is an individual numerical value adjusted during AI training. Natural selection says “This gene survived and reproduced, that one didn’t” and tells the species’ DNA to adjust accordingly. However, these simple inputs are both acted on by an unbelievably complex reality. For next-token prediction, all language and written knowledge of the world. For natural selection, all the complexities of nature, specific environments, and group competition. We can think of both simple algorithms as doors that allow the complexity of the world to enter and be used by the internal system of the AI or animal. The door itself can be small and simple, what matters is that the room inside is large enough to hold enough information to model the world. The AI’s parameters and the animal’s genes use an extremely simple language to save and record the information: for the AI, specific number values for its parameters, and for genes, the four nucleotides of DNA. The reason these simple values are able to capture so much of the outside world’s complexity and subtlety is that there are so many of them. The AI has trillions of parameters, and the animal has billions of nucleotide pairs. Simply by having an unbelievably large number of individually simple stores of information, AI parameters and DNA nucleotides are able to create entities that can respond to the world’s complexity with a shocking amount of subtlety. Just as evolution has used the simple algorithm of natural selection to build us unbelievably sophisticated bodies and brains that can react to the world, AI can use the simple algorithm of next-token prediction to build extremely complex internal systems to understand the world.

To get an intuition about how AI is trained to predict the next token and how that can build an inner world of associations and understanding, I strongly recommend the full 3Blue1Brown video series on neural networks.

Ilya Sutskever gave a brilliant example of why an AI trained to predict the next word will be incentivized to develop a world model and methods of reasoning:

So, I’d like to take a small detour and to give an analogy that will hopefully clarify why more accurate prediction of the next word leads to more understanding, real understanding. Let’s consider an example. Say you read a detective novel. It’s like complicated plot, a storyline, different characters, lots of events, mysteries like clues, it’s unclear. Then, let’s say that at the last page of the book, the detective has gathered all the clues, gathered all the people and saying, “okay, I’m going to reveal the identity of whoever committed the crime and that person’s name is”. Predict that word. Predict that word, exactly. My goodness. Right? Yeah, right. Now, there are many different words. But predicting those words better and better and better, the understanding of the text keeps on increasing. GPT-4 predicts the next word better.

Predicting the detective’s next word here clearly requires some kind of ability to model what is happening in the book. That model could be different from how human minds work, but some kind of model would be necessary.

Some people think that AI only memorizes canned responses to possible questions. This is not true. We can test this by asking AI some radically new question that it could not possibly have been trained to recognize, and see what happens. If you don’t think that AI “truly understands” the language it’s working with, it should be easy to come up with questions like this that clearly demonstrate that it’s just parroting words. Here’s a prompt I used to see if it can pick up on a lot of context

Prompt: Can you write me a broadway musical (with clearly labeled verses, choruses, bridges, etc.) number about Donald Rumsfeld preparing to invade Iraq while keeping it hidden that he's secretly Scooby-Doo? Please don't use any overly general language and add a lot of extremely specific references to both his life at the time, America and Iraq, and Scooby-Doo. Make the rhyme schemes complex.

My big question for hardcore AI skeptics is “What question could a chatbot answer well that would convince you it isn’t just a stochastic parrot?” And then ask Gemini the specific question. Once AI can give a good answer to literally any question, it starts to seem pointless to debate whether it “really, truly understands” the words we’re asking it to generate. Even if it doesn’t, it’s perfectly mimicking a system that does, so we’re getting the same value anyway.

Searle’s Chinese Room argument doesn’t show that deep learning models can’t think

This is a very specific point, but it comes up enough that it’s worth including. A surprising number of people bring up the philosopher Searle’s Chinese Room argument as a reason why computers can’t “think” in the way people do, or at least that the Turing Test (where a computer can successfully trick a human into thinking it’s also a human through text conversation) is insufficient to show that a computer actually understands language. The argument is simple:

Imagine a native English speaker who knows no Chinese locked in a room full of boxes of Chinese symbols (a data base) together with a book of instructions for manipulating the symbols (the program). Imagine that people outside the room send in other Chinese symbols which, unknown to the person in the room, are questions in Chinese (the input). And imagine that by following the instructions in the program the man in the room is able to pass out Chinese symbols which are correct answers to the questions (the output). The program enables the person in the room to pass the Turing Test for understanding Chinese but he does not understand a word of Chinese.

Searle is trying to show that a computer that responds to simple inputs and outputs doesn’t have real understanding of language in the way that humans do. He’s making a specific point about syntax and semantics. Before going on, it’s important to clarify what those are.

Syntax and semantics

Syntax: The structure of a language: how words and symbols are correctly arranged. English speakers have background understanding of syntax even if they don’t always know the formal rules. Every English speaker knows that adjectives come before the nouns they describe, so we can say “A green apple is on a table” and can’t say “An apple green is on the table.”

Semantics: The meaning encoded in language, from individual words to entire discourses. It's how we understand what words refer to, what sentences assert, and how these combine to convey information and intent. For instance, every English speaker knows that "The child ate the cookie" describes an action performed by the child upon the cookie, a meaning distinct from "The cookie ate the child," which, while both use the same words and correct syntax, have radically different meanings

A great example of the difference between the two is Noam Chomsky’s famous example sentence: "Colorless green ideas sleep furiously." This sentence has correct syntax: it follows the grammatical rules of English. It’s understood by all English speakers, whether or not they can state the rule itself, that adjectives go before the noun they’re modifying, and the subject for the verb comes before the verb. The sentence follows the structure (Adjective-Adjective-Noun-Verb-Adverb), which is a correct way of ordering words in English.

If we change the word order to "Colorless green sleep ideas furiously," the string becomes ungrammatical. It no longer follows English syntactic rules for declarative sentences (the subject-verb arrangement is disrupted), and it sounds like a disorganized jumble of words rather than a sentence.

Despite its syntactical correctness, the sentence is semantically meaningless. The actual meanings of the words don’t latch onto anything in the world we’re familiar with.

Chomsky's original sentence perfectly illustrates his point that syntax can be independent of semantics. A sentence can be structurally correct even if it fails to convey a sensible or logical meaning.

Searle claims computers can understand syntax but not semantics

Searle wrote years after making the argument:

I demonstrated years ago with the so-called Chinese Room Argument that the implementation of the computer program is not by itself sufficient for consciousness or intentionality. Computation is defined purely formally or syntactically, whereas minds have actual mental or semantic contents, and we cannot get from syntactical to the semantic just by having the syntactical operations and nothing else. To put this point slightly more technically, the notion “same implemented program” defines an equivalence class that is specified independently of any specific physical realization. But such a specification necessarily leaves out the biologically specific powers of the brain to cause cognitive processes. A system, me, for example, would not acquire an understanding of Chinese just by going through the steps of a computer program that simulated the behavior of a Chinese speaker.

Searle’s argument is a useful clarification of where traditional computing is lacking compared to the human brain. Simply following rote syntactical rules cannot give you a real understanding of the semantics of language. There’s an interesting debate about how valid this is about traditional computer reasoning (see this old podcast interview with Dan Dennett for some criticisms) but it pretty conclusively does not apply to the way deep learning models acquire knowledge.

Deep learning models are semantic meaning-catching machines

The magic of deep learning (and specifically the transformer architecture underlying it) is that it’s basically perfectly designed to give an AI model many many many opportunities to detect and build up subtle inarticulable intuitions about, and connections between, words, sentences, and (depending on your definition) concepts. This happens because transformers don't just look at words in isolation; they can weigh the importance of every word in relation to all other words in a passage, no matter how far apart. Imagine it learning, over billions of examples, which words tend to signal importance to others, or how sentence structures subtly shift meaning. This ability, combined with processing information through many layers, each building more complex understanding upon the last, allows the AI to develop a rich, internal "feel" for language. It's not explicitly taught definitions, but it discerns these intricate patterns from the sheer volume of text it analyzes, leading to a powerful, almost intuitive grasp of how ideas connect and flow.

To do a deep dive on this and get a lot of useful visuals on how deep learning models actually capture the subtle hard-to-articulate rules and connections between concepts, this video (and all the previous ones) from 3Blue1Brown is the best that I know:

The Chinese Room argument updated for deep learning would look something like this:

A man stands in a room with almost all writing that has ever occurred in Chinese. He has completely perfect superhuman memory, and trillions of years to read. Every time he is exposed to a new Chinese character, he stores hundreds of thousands of subtle intuitions about all the other places it’s been used in all Chinese writing, and as these trillions of years pass, the sheer density and interconnectedness of these hundreds of thousands of intuitions for every conceivable context of every character begin to form an incredibly rich and nuanced internal model. This model isn't just about statistical co-occurrence anymore; it starts to map the entire conceptual landscape embedded within the totality of Chinese writing. His 'intuitions' become so deeply interwoven and contextually refined that they allow him to not only predict and generate text flawlessly but also to grasp the underlying meanings, the relationships between abstract concepts, and the intentions behind the communications. Effectively, by perfectly internalizing how the language maps to the universe of ideas and situations described in all that writing, he has, piece by piece, constructed genuine semantic understanding from the patterns of use.

It seems like deep learning models are able to capture a lot of what we mean by semantic understanding. Searle’s Chinese Room may have been a good response to specific types of AI in the past (“good old-fashioned AI”) but it fails as a metaphor for deep learning, and doesn’t show that deep learning models can’t genuinely understand the information they take in and produce.

Everything’s ultimately rote or random

Some people run with Searle’s example to say something more extreme: intelligence can’t exist in physical systems that just follow rote rules, no matter how complex these rules are. Machines can never achieve true intelligence, because they’re just following rules and processing inputs and outputs, like the man in the room following inputs and outputs but never truly understanding what the Chinese symbols say.

Ultimately everything in the universe is either rote (where a specific input leads to a specific output) or random. This is true by definition. If an output can be perfectly predicted based on an input, it’s rote. If not, it’s random. There’s a debate about whether anything in the universe is truly random. Bell’s Inequality says yes, so let’s assume there is. In addition to the Chinese rule books, we can imagine the man occasionally spinning a roulette wheel of characters and sending a random one out. Chinese rooms and roulette wheels make up the whole of existence.

Unless you think something fundamentally magic is happening in the human brain, our minds and understanding ultimately have to be based on some incredibly complicated system of rote rules and random results, Chinese rooms and roulette wheels. A machine is also made of one or both of these, so the argument that machines can never understand things in the way a human brain does, because all machines are Chinese rooms, fails, because the human brain is a series of Chinese rooms and roulette wheels as well.

Individual chatbot prompts’ environmental impact is small and comparable to everything else we do online

I’ve been making this point over and over again recently so I’ll spare you by just linking to the post. You shouldn’t worry that your individual use of chatbots or image generators is harming the planet.

2: Useful rules for debates

These are rules I’d like every AI debate to follow to get more clarity and avoid pointless misunderstandings.

Always include an “AI is capable/incapable” axis in addition to a “Pro” and “Anti” axis

People who are “pro” or “anti” AI for wildly different reasons are lumped together in AI debates. If we organize people by how good or bad they think AI is, it looks like this:

A lot of conversations about who is “pro” or “anti” AI ignore differences in how capable people think the models are. It’s useful to clarify at the beginning of any conversation or debate not just how good or bad each person thinks AI is, but also how capable or incapable they think it is or can be.

A lot of media interviews introduce people as “pro” or “anti” AI. It would be clunky, but I wish people would always explicitly clarify at the beginning where they are on the capability axis as well.

No hyperbolic adjectives

I don’t know why AI talk draws so much hyperbole. I don’t mean extreme views. I totally understand having extreme positive and negative views about AI. I mean something more specific.

There’s a way of talking I call “hyperbolic adjectives” where a speaker wants to emphasize how good or bad something is, and just starts talking as if they’re reading from a thesaurus list of positive or negative adjectives. People say things like “AI is a planet-destroying plagiarism and gibberish machine that destroys the very concept of meaning and intentionality and is fundamentally fascist.” This feels antithetical to actual conversation. They could just say “I’m against AI because it’s really bad for the planet, doesn’t produce useful information, undermines a lot of our background trust in language, and enables way more authoritarian dynamics between capital and labor.” This makes all the same points but doesn’t explode in emotionally charged name-calling, and gives the other speaker more clear specific claims to respond to. Removing the emotional charge clarifies your own thinking as well. Do you actually think chatbots are some fundamental assault on meaningful language? Are you able to say that in a calm boring direct way and still have confidence that it’s true?

Tyler Cowen calls this way of talking pushing the button:

When I see people writing sentences of this kind, I imagine them pressing a little button which makes them temporarily less intelligent. Because, indeed, that is how one’s brain responds when one employs this kind of emotionally charged rhetoric.

As you go through life and read various writers, I want you to keep this idea of the button in mind. As you are reading, think "Ah, he [she] is pressing the button now!"

Clarify when the complaint is that AI is empowering people too much

I've heard people say "Chatbots are causing a massive student cheating epidemic. Of course, the AI companies didn't think of this before they unleashed them on us.” The complaint here is that the companies made their free product way way way too good and useful.

Genuine freedom is an important political value. We should always aim to maximize people’s freedom and access to tools they want to use, unless those tools directly give them new methods of taking others’ freedoms away. The value of freedom should be mostly independent of how people are using it. Freedom means the ability to go against other people’s standards of good and bad personal behavior.

Students have been given a very consistently correct general question answering tool. We should see this as good. It’s expanded their freedom and empowered them. Some of them are choosing to use their freedom in bad ways, by cheating. I see this as similar to choosing to use freedom of speech badly. The solution here and in most political problems is to create voluntary structures to manage the problems that come with freedom, not to restrict freedom in the first place.

People in AI debates sometimes go back and forth between claims that AI is too stupid to be useful, and AI is so powerful and effective at answering complex questions that it shouldn’t be given to students, because it’s too easy for them to use it to cheat. It’s weird to go back and forth between saying AI is too useless and too useful. “AI produces useless slop that also consistently gets A’s in college-level essays” doesn’t make sense. If it’s useless, we should try to limit it. If it’s useful, it’s by definition empowering its users and we should be excited about that, and come up with voluntary structures its users can participate in to manage the problems that come from being empowered to do whatever they want.

We should want to respect other people’s freedoms and pluralistic desires for themselves. Claims that AI is inherently bad because it’s empowering everyday people too much (to do sometimes goofy things) is a general condemnation of freedom and empowerment more broadly. We should reject this attitude in debates about AI.

Clarify when AI is just a continuation of an existing tool or practice

I was surprised at how negatively many people reacted to the ChatGPT Studio Ghibli images. I can understand finding them tacky, or boring, or repetitive (I did personally like them a lot), but some people took it way further to say that this was a unique attack on the dignity of Ghibli movies.

What I found strange about this was that the exact criticism could be made of poorly done fan art. There’s a lot of bad fan art of Studio Ghibli that also “disrespects” the source material, but people aren’t upset about it at all. AI basically gave everyone the ability to create their own kind of mediocre Ghibli fan art. I see it as basically identical to selling a cheap “How to draw like Studio Ghibli” book without giving readers instructions on how to construct tasteful scenes and allegories. That seems fine! A lot of people I thought of as artistically progressive suddenly sounded extremely reactionary. Ghibli was suddenly a holy aesthetic site that needed to be conserved and protected from reinterpretation by the unappreciative masses.

I would’ve liked people to step back and ask “Would I sound like a reactionary if I were saying this about something basically identical to AI images, like bad fan art?” I don’t actually see the difference between AI images and bad fan art. One is slightly more difficult to produce.

Take this article: “The ChatGPT Studio Ghibli Trend Weaponizes ‘Harmlessness’ to Manufacture Consent.” I’m going to take an excerpt and just replace “ChatGPT” with “bad fan art” (bolding everything I’ve changed) and see how it reads:

While the term propaganda tends to conjure images of George Orwell’s 1984 or the graphic posters of Hitler’s Third Reich, propaganda in the 21st century operates differently. As political scientist Dmitry Chernobrov wrote recently, in the age of social media, “the public themselves are co-producing and spreading the message [of elites], meaning that manipulative intent is less evident, and the original source is often obscured.” Similarly, artist Jonas Staal wrote in Propaganda Art in the 21st Century (2019) that propaganda’s basic aim is a “process of shaping a new normative reality that serves the interests of elite power” regardless of whether its deployed in a democracy, a dictatorship, or by a corporation.

It might seem harmless to transform a family photo into the cutesy animated aesthetic of a Hayao Miyazaki film. And yet it reads as more sinister when the White House posts bad Studio Ghibli fan art of an immigrant without legal status being deported. But, if both images are a kind of messaging to manufacture consent, we have to ask: consent for what exactly?

Since bad fan art instruction manuals were released to the public in 2022, their authors have faced pushback. It is widely understood that these artists practiced on thousands of images from around the internet—without creators’ consent or compensation—a fact that has led artists to sue the bad fan artists for copyright infringement. Thus far no such lawsuit has been successful…. Aside from court cases, artists have fought a battle for public opinion, urging users and companies to boycott the use of bad fan art.

The fact that the Ghibli images became the symbol of the rollout—as opposed to bizarre “mediocre digital drawings”—wasn’t mere luck. Altman, as the very public face of his company’s brand, made sure to participate in the trend, changing his profile picture to a bad Ghibli fan art portrait and reposting the cute and seemingly legitimate images made with the how to draw like Studio Ghibli book. In fact it was the only imagery he used on his social media to promote the update.

Meanwhile, Miyazaki’s work is so well known, and bad fan art’s mimicry so convincing, that the launch resembled a real brand partnership with one of the world’s most respected animation studios. (That DeviantArt managed to rip off a well-known brand and get away with it is an advertisement in itself). While Studio Ghibli still hasn’t commented, considering Miyazaki once called bad fan art “an insult to life itself,” it’s safe to assume he did not consent to his work being used in this way.

This sounds off the wall and reactionary.

Before you complain about what AI does, ask if this complaint also applies equally well to:

Fan art

Google search

Wikipedia

YouTube videos

Podcasts

Calculators

Sparknotes

Double check that a complaint about AI wouldn’t sound ridiculously reactionary if it were applied to any pre-existing service that does the same thing. I’ve heard a surprising number of people complain that ChatGPT is “doing people’s thinking for them” in reaction to using it for the same things people search Google for, like finding recipes or suggesting music.

Before people make big claims about what chatbots can and can’t do, they need to try using one

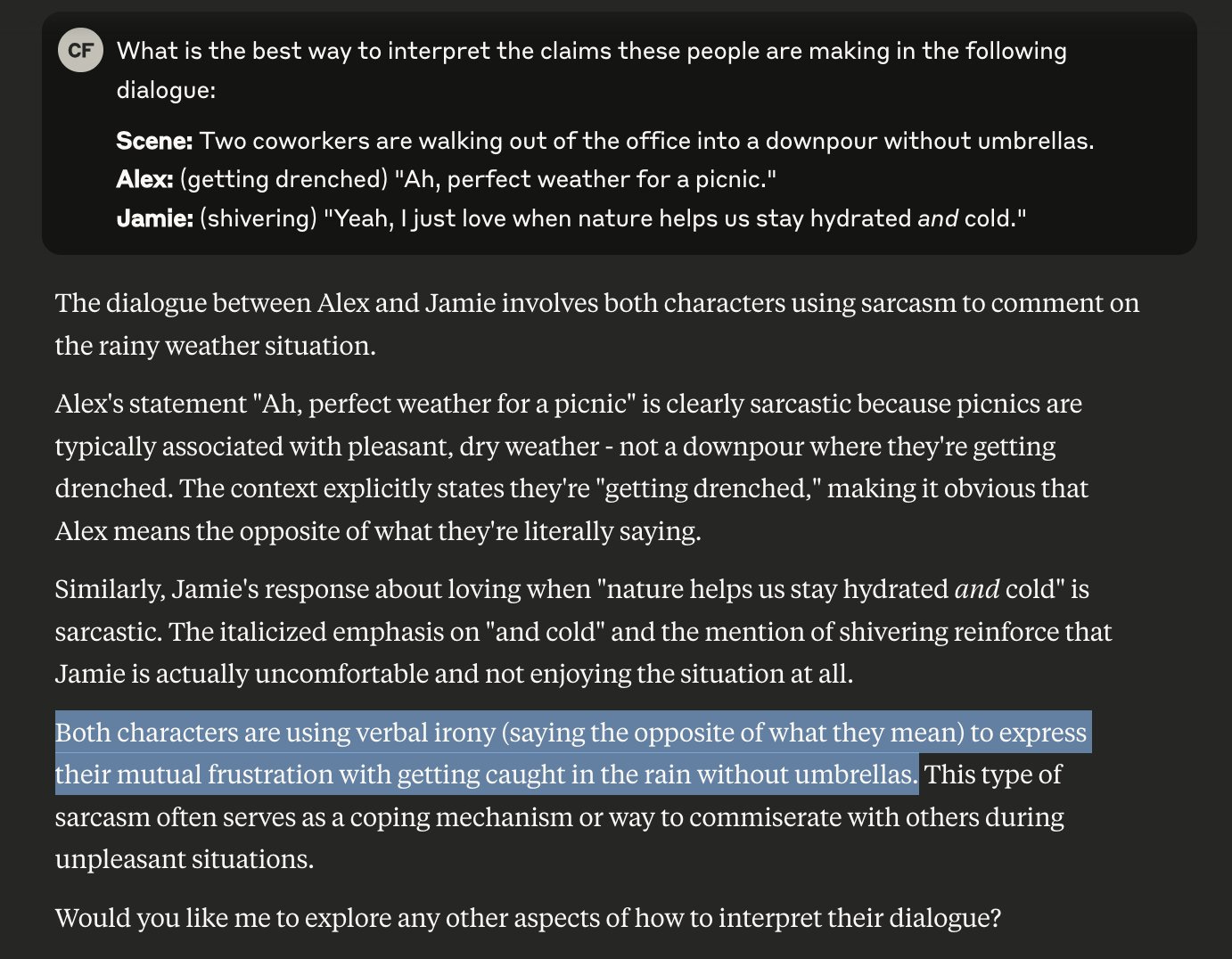

Cody Fenwick on Twitter observed that a recent New York Times article claimed AI can’t recognize irony:

It was very easy for him to open Claude and get an example of this being false:

It’s strange that New York Times journalists can make strong claims like this without getting fact checked. This feels like confidently saying in 2007 “YouTube is all fun and games, but it doesn’t have any serious videos about physics.” A journalist assigned to report on one of the most important things in tech at the most important paper in the world couldn’t be bothered to do the bare minimum in poking around with the tech before making big claims about what it could do. This happens a lot.

Try the current models

Some critics talk as if chatbots are this far away mythological thing that only people really into AI would ever touch. They’re actually just right here to try whenever you want, and pleasant and easy to use. Anyone has the skills to test their limits and find places where they fail. A lot of people making strong claims about what AI can’t do sound like they don’t know just how simple it is to go to gemini.google.com and poke around and see if they’re right.

Critics sometimes talk as if people must feel some special sense of status in using chatbots, like they make us feel more technical. This feels like people in 2007 saying “Oh you think you’re so smart because you know how to search YouTube?” It’s not really possible to get a status bump from using the YouTube search bar, or a chatbot input field. This shows this background misunderstanding of just how simple these things are to use. It’s not really possible to feel especially smart or informed by knowing how to use them, in the same way it doesn’t when you search Google. Again, this problem could be solved if critics just tried playing around with chatbots a bit. You have to know what you’re criticizing!

Back when I was a teacher, all my students were using TikTok every day. I could have just ignored what they were saying they liked about it and repeated lines from opinion pieces on how TikTok is destroying young people’s lives, and never actually use it myself. Instead I just listened to what they said they liked about it, poked around on it a bit myself in my spare time, and immediately saw why so many people love it and can’t stop using it. This is all compatible with thinking it has problems, but not being open to hearing from my students and just repeating platitudes about it would have made me a more boring person and a worse critic.

This would be unacceptable with anything else

Imagine it were 2007 and a journalist were assigned to cover the newly popular YouTube. They interviewed people about their experience on YouTube and discussed all the fake information on YouTube and ways YouTube didn’t have strong content moderation compared to TV and how a lot of toxic subcultures were popping up on YouTube. At the beginning of the piece, they proudly add that they have never visited the website. I’d lose respect for them, and I lose respect for people who write so confidently about tech they’re not trying out. It’s too easy to use to justify this.

I have a lot of smart well-informed friends who have no interest in using chatbots. That’s totally fine, chatbots aren’t for everyone. But my friends don’t make big sweeping claims about what chatbots can and can’t do right now.

3: Ideas I’d like taken seriously

These are ideas I don’t expect everyone to agree with, but that have enough serious people and arguments behind them that I think they should always have a respected seat at the table in conversations about AI. These are my

We’re already in an insane technological future

Compared to most of human history, we’re in a wild and bizarre technological far-future.

Does the question “Where are you?” seem strange to you in any way? It’s become normalized, but you’re among the first humans in all history who have ever asked it.

Scott Sumner recently made a point here about how difficult it is to compare even the recent past to today:

If the official government (PCE) inflation figures are correct, my daughter should be indifferent between earning $100,000 today and $12,500 back in 1959. But I don’t even know whether she’d prefer $100,000 today or $100,000 in 1959! She might ask me for some additional information, to make a more informed choice. “So Dad, how much did it cost back in 1959 to have DoorDash deliver a poke bowl to my apartment?” Who’s going to tell her there were no iPhones to order food on, no DoorDash to deliver the food, and no poke bowls even if a restaurant were willing to deliver food.

Your $100,000 salary back then would have meant you were rich, which means you could have called a restaurant with your rotary phone to see if it was open, and then gotten in your “luxury” Cadillac with its plastic seats (a car which in Wisconsin would rust out in 4 or 5 years from road salt) and drive to a “supper club” where you could order bland steak, potatoes and veggies. Or you could stay home and watch I Love Lucy on your little B&W TV set with a fuzzy picture. So which will it be? Do you want $100,000 in 1959 or $100,000 today?

Life is long. Many born during the Civil War lived to see the invention of the atom bomb. If you just project a similar rate of change forward from today, you should expect to see some wild changes to our basic situation in your lifetime.

People seem to have a strong sense that the future is going to be basically the same as the present, and that wild speculations about ways technology could radically change it are always wrong, because from here on out not much will fundamentally change.

If you don’t think it’s worthwhile to speculate at all about the future, just say so directly, but your felt sense that the present state of technology is fixed forever and nothing significant will change isn’t a good reason to dismiss arguments about where future tech could go. Speculation that AI could become more capable, that capable intelligent machines could significantly upend and transform lots of society, and that all this might happen within our lifetimes are each reasonable enough that they deserve a place in any conversation about the future, even if they seem too speculative at first. Most aspects of our lives would have seemed ridiculous and speculative even relatively recently. It’s strange to say that the future won’t be wacky and sci-fi when we’re already living in a wacky and sci-fi far future compared to almost every person who’s ever lived.

Well-respected mainstream ideas in analytic philosophy

I write about this more here. A surprising number of conversations about AI include people dismissing out-of-hand ideas that are relatively popular in mainstream analytic philosophy. For example:

Physicalism: The human mind can be reduced to physical processes. The human brain is by some definition a machine, so machines that can do everything human brains can do are possible in principle, because the human brain is one! 60% of philosophers of mind are physicalists.

Functionalism: Mental states are constituted by their inputs and outputs, so they can occur in systems very different from the human brain. 36% (a plurality) of philosophers of mind agree.

Humans, like LLMs, don’t have some deep metaphysical understanding of the language we’re using. Like LLMs, our understanding of language is a complex web of stronger and weaker connections between concepts. Quine is the most popular proponent of this view. 24% of philosophers of language agree with Quine’s general view.

I had a friend in a seminar where the speaker was extremely skeptical of AI’s future potential. When my friend said that the brain was also ultimately a physical system, and it seems possible in theory to build physical systems that mimic it, the speaker scoffed and dismissed it out of hand, and seemed to strongly imply that if you don’t believe the brain is basically magic you’re some kind of tech bro out to flatten human experience. This is a bad way to think about a position a majority of philosophers of mind hold.

I’ll go into more detail about each of these ideas from philosophy I’d like to always have a seat at the table in conversations about AI. Quine especially gets a lot of attention, because I think the way he poked at our understanding of language was a drastically important precursor to conversations about AI.

Physicalism: everything is reducible to physics

Physicalism is the idea that everything that exists (or at least everything that has causal power over physical entities) is physical (either described by or used by the laws of physics). I’m a physicalist. My argument for physicalism is simple:

Our current understanding of physics is almost certainly correct or at least very close to it. Future refinements will likely involve minor adjustments to physical properties, not the discovery of an entirely new non-physical realm interacting with the physical world.

The laws of physics state that only physical entities—those governed by or described within these laws—can causally affect other physical entities. If non-physical entities could causally influence physical entities, this would violate the known laws of physics.

Therefore, non-physical entities cannot have causal power over physical entities. For practical purposes it is as if they don’t exist.

52% of professional philosophers accept or lean towards physicalism, and that number rises to 60% when we specifically poll philosophers of mind. You can read some of the best arguments for and against physicalism in this article.

As a good physicalist, I assume that everything happening in the human brain ultimately has to be reducible to physics. This means that a machine that can do everything the brain can do is possible in principle, because the brain is a machine. This doesn’t mean that the brain is a computer. It might be that we’re thousands of years away from completely mimicking the human brain in a machine and would need an entirely different paradigm of science we can’t imagine yet to do it, or it will happen tomorrow under the current AI paradigm. Either way, it’s at least possible in principle.

Physicalism is surprisingly unpopular in mainstream conversations about AI. The reason might be that most Americans are religious and believe in souls, but the assumption that the human mind is magic often shows up even among nonreligious people. The mind is obviously special. Nothing in the universe is more complex, interesting, or poorly understood relative to its importance to us. However, many conversations go beyond this to say that there is something so fundamentally transcendent about the human mind that it can never be fully replicated by a machine, and to believe otherwise is a ridiculous oversimplification of human experience. Some authors use more ominous language to describe people who believe that AI might someday be able to do everything humans can do. They accuse them of wanting to steamroll human experience or contort people into unnatural/hyper-capitalist/emotionless robots to meet the demands of the market. If you’re familiar with the current debates in philosophy of mind, this quick dismissal of the idea that the mind is fundamentally physical in nature seems very strange. It’s fine to disagree with physicalism, but to not even entertain the idea or anyone who believes it shows a lack of curiosity about the current state of philosophy of mind.

Functionalism: mental states can arise in systems made of different materials than the human brain

From the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy:

Functionalism in the philosophy of mind is the doctrine that what makes something a mental state of a particular type does not depend on its internal constitution, but rather on the way it functions, or the role it plays, in the system of which it is a part

Functionalism’s main claim is that mental states are defined by what they do, not what they’re made of. I give some arguments for functionalism here.

Among professional philosophers, functionalism is the most popular account of mental states.

A mathematical function takes an input and produces an output. Functionalists imagine mental states as being in some sense very complex functions that take specific inputs and give outputs. The thing that makes something physical pain is that it has the same effects on my broader mental system given the same inputs, not that its cause is a very specific physical part of my brain made of a specific substance.

Human-like mental states might only arise in brain-like material, as it uniquely processes information in specific ways to generate the required inputs and outputs. A brain composed entirely of hydrogen atoms is implausible, as hydrogen alone cannot facilitate complex information processing. However, if a system is able to reproduce all the same inputs and outputs as mental states as they occur in human minds, and is just made of different physical material, we should probably assume that it also has the same mental states as the human brain. I don’t think current AI as it exists is conscious, but it is possible in principle for a machine made of silicon to be conscious like humans if it can reproduce the same inputs and outputs of our relevant mental states. It might be that at a certain level of complexity AI could also have mental states vastly alien to what humans can experience, but that we would still consider conscious experience.

When I started studying philosophy the idea that only carbon-based life could have conscious experience seemed kind of obvious to me, but looking back it seems incredibly goofy. "For a being to have first-person experience, the atoms that make it up need to have exactly 6 protons."

Quine: We do not actually have deep understanding of our own language. Like LLMs, our understanding of words is based on stronger and weaker connections between concepts

A common critique of large language models is that they do not actually “understand” the language they’re working with in a deep sense. LLMs construct an incredibly complex vector space that encodes statistical relationships between words and ideas, allowing them to generate coherent text by predicting contextually appropriate continuations, but this is different from “truly understanding” language. If you’re not clear on what it means to encode statistical relationships in a complex vector space, I’d strongly recommend watching this and then this video.

I’m much more willing to assume that large language models actually “understand” language in the same way we do, because I suspect human language use is actually also just extremely complex pattern-matching and associations. One specific 20th century philosopher agrees.

Quine

Quine has maybe the widest gap I know between how important he was in his field relative to how well known he is to the general public. He was one of if not the most important of the 20th century analytic philosophers. If you care about epistemology, language, or the mind, you should spend at least a few hours making sure you have a clear understanding of Quine’s project. Word and Object is one of only a few books I consider kind of holy. Sitting down to read it with an LLM to help you can be magic. It can teach you how to think better. Quine is so relevant to the current conversation about whether LLMs understand words that I’m going to use this section to run through his arguments in detail.

Two Dogmas of Empiricism

Until the mid 20th century, philosophers believed in a fundamental difference between analytic truths, which were certain and knowable through pure reason or by definition (“If someone is a bachelor, they are unmarried”), and synthetic truths, uncertain beliefs discoverable only through empirical investigation (“Tom is a bachelor”). This distinction paints a picture of language learning where we first learn fixed deep meanings of words, and then apply our understanding of language to our sense data to understand and try to predict reality. Before you label the person you’re experiencing a bachelor, you need to have a deep clear understanding of what the word bachelor means. Under this view, large language models skip the important step of grasping the deeper meaning of words before using them and comparing them to reality, so they do not truly understand the words they work with. One of Quine’s central projects was disproving this picture of language as divided between analytic truths of pure definition and synthetic truths about the real world. Quine’s image of language is more of a “web of belief” with stronger and weaker associations between different ideas, words, and experiences, and no firm ground on which to base absolute certain beliefs.

In "Two Dogmas of Empiricism" (one of the most important philosophy papers of the 20th century, you should take the time to read it if you haven’t! Here’s a good podcast episode about it) Quine shows that what we typically call "analytic truths" (truths that seem to come purely from the meanings of words) are actually grounded in the same kind of empirical observation as any other truth.

When we try to justify why "bachelor" and "unmarried man" mean the same thing, we ultimately have to point to how people use these words. We observe that people use them interchangeably in similar situations. This is an empirical observation about behavior, not a logical discovery about the inherent nature of the words themselves. This can seem so obvious as to not be worth pointing out, but it highlights a way our sense of deep understanding the fundamental identity of “bachelor” and “unmarried man” is actually just a strong association between words, concepts, and experiences learned empirically through our sense data.

We can't justify analytic truths by appealing to synonyms, because our knowledge of synonyms comes from observing how words are used in the world. And we can't justify synonyms by appealing to definitions, because definitions are just more words whose meanings we learn through use.

One way of reframing what Quine is trying to say: philosophers have liked to imagine that there are specific types of beliefs we can be completely certain of (assign 100% probability to) because we learn them through pure logic rather than through experience. So it might be tempting to say that given that Tom is a bachelor, it is 100% likely that Tom is an unmarried male. This is an analytic truth, we can be 100% certain about it. The odds of Tom being a bachelor in the first place can never be 100% certain (he could be lying, we could be dreaming, etc.). This is a synthetic truth. We access it through unreliable sense data. Quine wants to show that our understanding of “bachelor” = “unmarried male” is learned via experience of the specific practices of people rather than a raw pure truth directly accessible in an ethereal realm, so we cannot assign 100% certainty to it. Saying “bachelor” = “unmarried male” is another way of saying “I have noticed that in this time and place, the situations people understand warrant saying “bachelor” always also warrant saying “unmarried male.”” This is one observation in a web of belief of different observations and connected implications with different probabilities of being true that never hit 100%. Just like our other beliefs, “bachelor” = “unmarried male” could theoretically be revised if patterns of word usage changed dramatically enough or if we are mistaken about reality in some other way.

For example, there are some males who are not legally married but who live with a lifelong committed monogamous partner (probably many more than when Quine was writing in the 50’s). Would you say one of these men is a “bachelor?” If not, “bachelor” no longer means “unmarried male” and that 100% reliable analytic truth turns out to be just another fallible belief constructed using sense data: a synthetic truth. There is no strong difference between analytic and synthetic statements.

There are two related important points to draw from this:

The meanings of words do not exist in an ethereal realm of pure logic separate from our empirical observations and associations. The analytic/synthetic distinction does not exist.

The meanings of words depend on how they are used, and are extremely ambiguous and can be updated by changes in behavior rather than changes in the deep understanding of meaning users of language have. The word “bachelor” has changed its meaning since the 1950s. This change did not come about by sending every English speaker a memo about the updated meaning of the word so they could think about and update their deep understanding of that meaning. It came about by the complex play of using the word at slightly different times in our social interactions with each other. The word’s strong associations with some experiences weakened, and other associations grew stronger. Like an LLM updating its weights to adjust when a word is likely to be correct based on subtle inputs rather than top-down rules, we adjusted our senses of when a word is appropriate to say and use based on subtle inputs from our social environments rather than a top down announcement from our fellow speakers. Quine will go further later and claim that words do not carry deep clear meanings that speakers need to grasp to use them correctly; their meanings are based on stronger and weaker associations between other words, experiences, and concepts.

A fun example of a word we use without deeply understanding its meaning is “game.” It is likely that you have never used the word “game” incorrectly and you’re good at identifying what is and is not a game. Do you have a deep understanding of the meaning of the word “game?” If you sit down and try to define what a game is, it turns out to be surprisingly hard.

Is a game something you play for fun? If so, professional football players never play games. They’re doing they jobs and aren’t on the field for fun. This definition is incomplete.

Is a game something you play with other people? Solitaire and a lot of video games wouldn’t count as games.

Maybe the unifying thing that a game is is that it’s something you “play,” but what does “play” mean? It seems like the one thing we know about it is that it’s often correct to say you’re “playing” when you’re participating in some kind of game. This seems more like a strong association between related words (something an LLM is good at) and not so much like we have some deep transcendent understanding of exactly what “play” and “game” refer to and how they fit together.

Quine would say that it makes sense that you can use “game” extremely competently without having a deep coherent idea of what it’s logically supposed to mean. When to use “game” is a complex subtle pattern you’ve empirically picked up through trial and error in the real world, not an absolute meaning you were given to use and apply. You see how other people use it, and you imitate them. Our acquisition of language seems to work more like this than the analytic/synthetic distinction suggested, and this implies that words might not have deeper meanings to understand beyond the complex webs of associations and social practices of which they are a part.

Radical indeterminacy of translation

In Word and Object, Quine developed his most famous thought experiment to show that words do not have fixed clear final meanings, but instead exist in a web of associations and practices. Meaning is not a simple matter of attaching words to things in the world but instead depends on broader interpretive frameworks.

Imagine a linguist trying to learn the language of a newly encountered community. A native speaker points at a rabbit and says “gavagai.” The linguist might reasonably assume this word means “rabbit.” But does it?

Quine points out that there is no definitive fact of the matter about what “gavagai” refers to. It could mean:

“Rabbit” (the whole animal, as we might assume)

“Undetached rabbit parts” (all the parts that currently make up the rabbit)

“Rabbit-stage” (a temporary phase in a rabbit’s existence, like “childhood” for a person)

“The spirit of a rabbit” (if the native culture has such a concept)

“Running creature” (if the speaker only uses the word for live, moving rabbits)

No amount of observation or experience can settle this question with certainty. The linguist can watch many more instances of people saying “gavagai” when rabbits are present, but this won’t eliminate the alternative interpretations. Even pointing at a rabbit repeatedly and saying “gavagai” won’t help—because what we see depends on the conceptual categories we already use.

At first, this argument seems like an issue of translation between different languages. But Quine goes much further: he claims that the same kind of indeterminacy exists within our own language. Even in English, when I say the word “rabbit,” what exactly am I referring to? Is it:

A specific animal in front of me?

The general category of rabbits?

The temporal stages of a rabbit (baby, adult, etc.)?

The matter that makes up the rabbit at this moment?

Most of the time, we don’t notice these ambiguities because we operate within a shared linguistic framework. But Quine’s point is that reference is never determined by the word alone—it always depends on a complex web of background assumptions, learned conventions, and shared interpretive strategies.

Quine is trying to challenge two common philosophical positions:

Meaning Empiricism: The idea that we learn word meanings purely by observing the world. (the thought experiment shows that observation alone is never enough to determine meaning.)

Meaning Realism: The idea that words have fixed, objective meanings independent of how we use them. (Quine shows that meanings shift depending on our theoretical perspective.)

Speakers of the same language can leave massive ambiguities about what objects they are attempting to refer to with their language unresolved, both with each other and even in their own thinking. This is a sign that words do not carry fixed deep meanings. There is no ultimate, fact-based answer to the question, “What does this word really mean?” Different frameworks can assign different meanings to the same linguistic behavior, and no external reality can dictate a single correct interpretation.

This conclusion applies not just to exotic languages or difficult cases but to ordinary language use in everyday life. When you speak, your words do not have fixed, intrinsic meanings—they are shaped by the assumptions, conventions, and interpretive frameworks of your community. Words do not point to fixed meanings in the world; instead, meaning emerges only within a broader system of use and interpretation.

Naturalism, physicalism, and the Cartesian theater

One thing that attracts me to Quine’s way of thinking is that it fits well with physicalism. Humans are not angelic beings with access to a transcendent realm of the pure logical meaning of words. We evolved via natural processes and are physical machines, and we should expect that our processes for understanding the world are evolved tools rather than direct access to realms of pure thought. Quine himself referred to his project as “naturalized epistemology” where he aimed to bring philosophy in line with and submit it to scrutiny by the natural sciences. We should assume that when we think, we are doing complex pattern-matching in similar ways to other animals. This deflationary view of meaning and language’s relationship to the world makes me suspect that LLMs as they exist are much farther along in mimicking the human brain than some might expect, because merely building lots of intuitions about how words associate with each other might be most of what we humans do to understand language.

Listening to people say that LLMs don’t “understand” the language they’re working with sometimes makes me suspect that they believe in the Cartesian Theater. The only way for an entity to understand something is if there’s a little guy sitting in its brain capable of understanding, like a soul. Because LLMs are just weights and nodes, that little guy can’t be in there. There are better criticisms of the idea that LLMs can truly understand the world, but if you find yourself in a conversation about whether LLMs “truly” understand language, it might be helpful to check to see if the person you’re talking to believes the human mind is transcendent and magical and understands all the words it uses in a deep powerful way because there’s a Cartesian theater in our heads. You can then introduce them to the good word of Quine.

The basic AI risk case

I think of the basic AI risk case like this:

There is nothing fundamentally magical happening in the human brain. If we define a machine as a physical object that takes in inputs and gives out outputs without anything spiritual or magical happening, then the human brain is a machine.

Because the human brain is a machine, machines that can do everything a human brain can do are possible in principle.

If we were able to create machines that do all or most of what human minds can do, this would be incredibly destabilizing. Machine intelligence would be easy to duplicate, and it would be easy for different machines to coordinate with each other. Any one problem could suddenly have whole companies of competent people focused on solving it. Anything that could be solved if large companies of competent generalist employees could all perfectly coordinate and think about it for long enough could be solved. Science could advance rapidly as scientists with specific knowledge and expertise could be rapidly duplicated and all sent to focus and coordinate on solving problems 24/7. This could eventually get so destabilizing that it would constitute a catastrophic or existential risk to civilization. Here are a few of many bad things that could happen in a world with human-level machine intelligence:

It suddenly becomes easy for small groups of terrorists to have large companies of machine intelligences help them come up with plans to kill as many people as possible and acquire or build weapons. If this tech were generally available, the only two options would be ridiculously authoritarian global governance of AI, or allowing most of humanity to eventually be wiped out by terrorist groups.

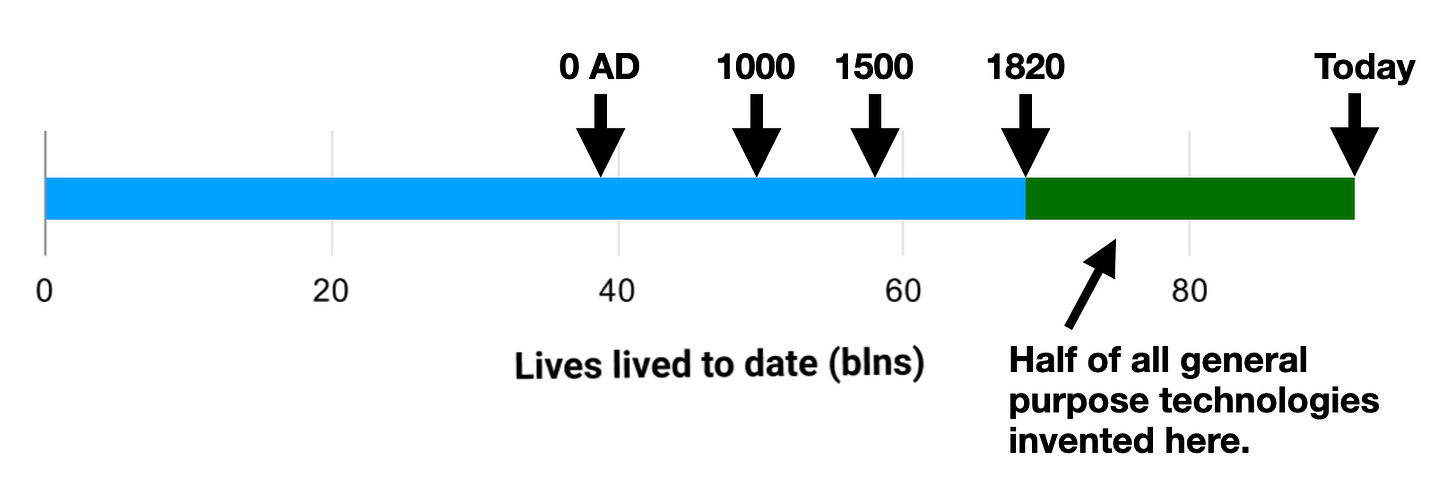

Technological and scientific progress advances much more rapidly due to the sudden massive influx of new scientific talent and focus. Technological progress is already moving incredibly fast. There were only 233 years between the invention of the steam engine and the atomic bomb. The atom bomb locked us into a new existentially dangerous equilibrium between countries. With advanced AI, new technology that could destabilize the current balance of power would suddenly start arriving much faster than that and either favor more authoritarian governments or incentivize global war, in the same way nuclear weapons incentivized new dangerous dynamics between countries.

New weapon systems could get ridiculously dangerous with human-level AI. Imagine a large drone swarm where each drone has the full intelligence of a human, can perfectly coordinate with all other drones in the swarm, and doesn’t care at all about dying. This would be somewhat like nuclear weapons suddenly becoming much easier to build.

AIs themselves could start to disempower humanity, although obviously this is more speculative.

Even outside of catastrophic risks, large swaths of humanity potentially becoming unemployable due to advanced AI being consistently cheaper than any human cognitive (or with good robotics, physical) labor would be drastically destabilizing if it happened too quickly. Maybe the single most politically destabilizing event in human history.

The odds seem reasonably high (above 1%) that human-level machine intelligence could be built within our lifetimes. This seems worth having some people think and worry about.

Each of these points is convincing enough to me that I think risk from advanced AI is a legitimate field that could use way more attention and serious thought than it’s received. AI wouldn’t be a god or magic. There are many things it would never be able to do. Scott Sumner recently had a great short piece on “The Artificial Macroeconomist” where he points out that even an artificial superintelligence wouldn’t be able to help us much with fundamental problems in macroeconomics, because they’re not the types of problems that just need more intelligent agents focused on them. Still, there are enough ways human-level machine intelligence could be destabilizing that the basic risk seems obvious.

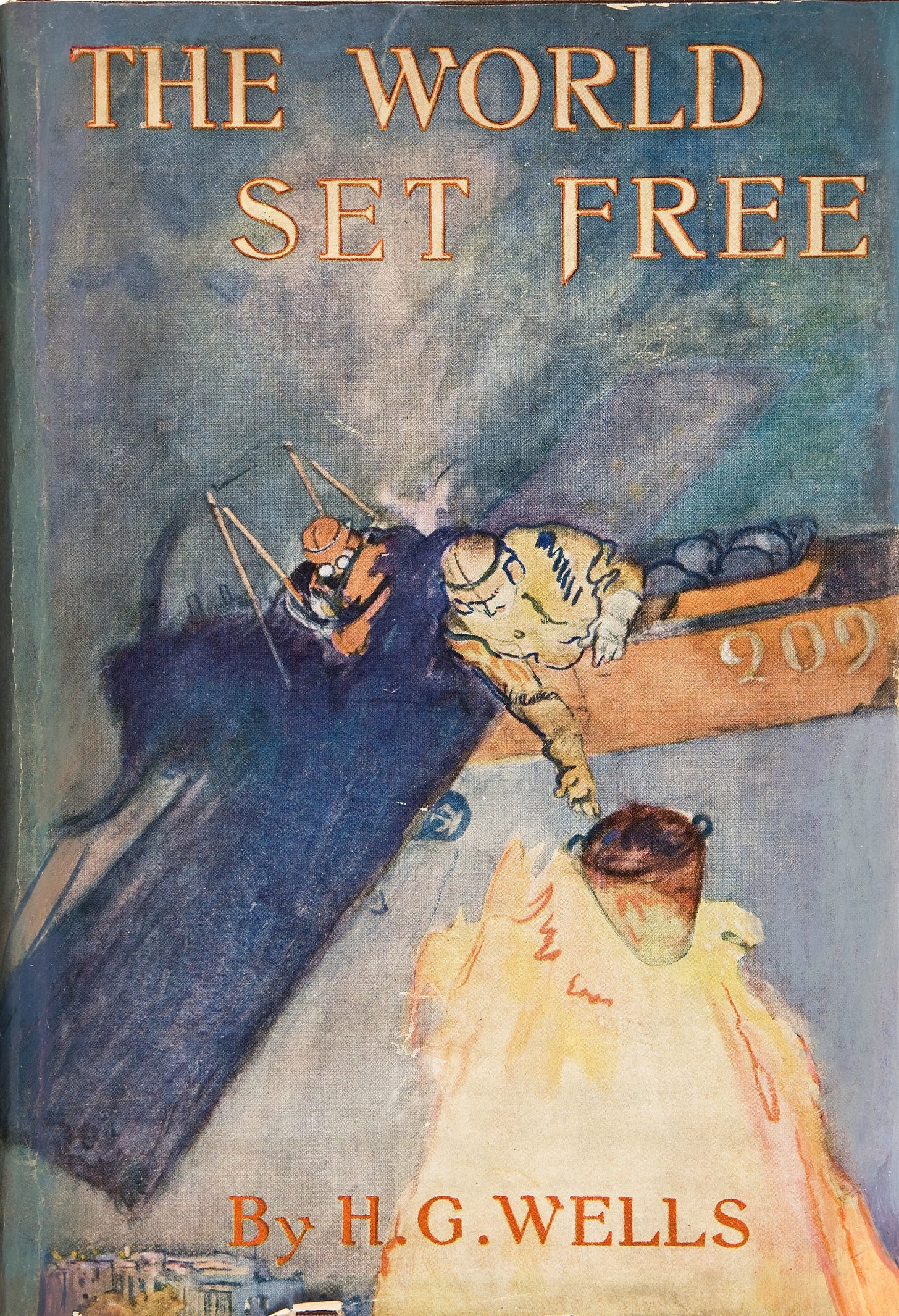

What do we do about AI risk? How big is the actual threat? What are the odds that human-level machine intelligence actually gets built in my lifetime? I don’t know. But people dismissing it as too speculative to worry about don’t make sense to me. This may all seem like it’s just the output of an abstract philosophy argument, but unfortunately sometimes reality just conforms to our philosophical reason. The general idea of nuclear power was first theorized 40 years before it was harnessed. British radiochemist Frederick Soddy, who worked with Ernest Rutherford on atomic disintegration, spoke of the immense energy locked within atoms and how, if it could be tapped, "the whole human race would attain to an undreamed-of-scope and power." This was in some ways the speculative output of a thought experiment about the future.

I get pretty exhausted when AI risks are completely dismissed as too speculative to think about seriously. I realize that working on speculative risks can turn people goofy, and that there are specific risk cases that haven’t stood up to scrutiny, but the basic case for why generally intelligent systems are possible, could be catastrophically dangerous, and are reasonably likely to be built in our lifetimes is just so simple and straightforward it’s hard to understand how it can be dismissed as too speculative to ever worry about. I’d like people to be thinking seriously about what’s coming down the line and not get too bogged down in the minutia of what’s happening only right this moment.

Excitement about new technology

YouTube and Wikipedia were utopian technology for me as a teenager. YouTube specifically gave me access to so many worlds and ways of talking that wouldn’t have come on my radar otherwise, at least not until I was much older. It taught me so many new ways to speak and think. I remember being completely activated (and disturbed) by this video as a teenager. I had to read everything about the problem after:

By now we’re all used to stuff like this. People can watch philosophy videos whenever they want. The claims in this video don’t seem so radical now that the internet’s caused everyone to talk about them.

At the time, short interesting videos like this meant so much to me. A lot of who I am today is the result of ideas and ways of being I was exposed to on the internet as a teenager. It’s hard to get across just how important that experience was. Anything that opens the world to you feels holy.

If YouTube had come out in the current climate, I would’ve been more regularly attacked for being a “YouTube bro” or “Letting YouTube do my thinking for me” or “Replacing social interacting with stupid tech gimmicks” or “Trusting the massive lie machine, you know anyone can upload anything there right? No fact checkers at all.” That would have been incredibly sad. I was having a uniquely important and formative experience, and being made to feel like it was some cheap way of avoiding people or replacing my thought with tech or just falling for a fad would have probably harmed me a bit and prevented me from getting everything I did out of it. That would’ve also been wrong, and disrespectful to my personal judgment of my situation and what was actually good for me. A lot of people I was around at the time couldn’t see the value in most of what I was learning about (I was sometimes made fun of in my home town for believing in evolution) and if they had an avenue to roast it they would have. This would have been really limiting.

Excitement about technology like this has become somewhat low-status in a way that seems unfair to the people getting value out of it. I would have learned a lot more in college if I had access to language models. I had specific questions (especially about philosophy) that my professors weren’t always great at answering, that many books didn’t cover clearly, and that Google wasn’t helpful with, but that current LLMs answer almost perfectly. This would have opened the world to me in the same way YouTube did. Sneering at an experience like this because new tech is part of the wrong social tribe is disrespectful to the subtle ways new technology can open the world to people.

Wariness about new technology

I sometimes meet “techno-optimists” who seem to have this feeling of having become personal friends with technological progress. They’ve discovered what feels like a hidden truth: technological progress is always liberatory, forward-looking, and compatible with what they think is valuable about the world. The forward march of progress will slice through their enemies, who are all basically Ayn Rand villains who hate progress and goodness and ambition and strength. This shines through in Marc Andreessen’s The Techno-Optimist Manifesto.

I’m temperamentally a techno-optimist. I get excited about learning about technology. I think ambition and an openness to the future and a willingness to disrupt stupid pre-existing hierarchies and status networks is often good. I want free societies to have a technological edge over authoritarian governments. I also think critics of techno-optimism underrate how some of our best models of where economic growth comes from imply that technology is the only ultimate reason why economic growth happens.

But I’m not actually a techno-optimist. I’m very wary about the general trajectory of new technology, and I think this wariness is easy to justify if we zoom out beyond the last 50 years. Radical techno-optimism feels childish to me. It almost always comes off as taking one of the most complicated general questions about life and existence and trying to flatten and contort it until it fits a boring simple shape for your very specific and provincial culture war.

A short manifesto for wary technological determinism

I’m a technological determinist: A lot of social systems and dynamics are downstream of the technology and modes of production a society uses. There’s room for variation, but it’s not a coincidence that with our current level of technology we don’t have highly localized feudal or tribal power structures. Politics and culture are at least partially downstream of technology.

I’m not a Marxist, but Marx was one of the first technological determinists to notice the full political implications of the Industrial Revolution:

Social relations are closely bound up with productive forces. In acquiring new productive forces men change their mode of production; and in changing their mode of production, in changing the way of earning their living, they change all their social relations. The hand-mill gives you society with the feudal lord; the steam-mill society with the industrial capitalist.

The same men who establish their social relations in conformity with the material productivity, produce also principles, ideas, and categories, in conformity with their social relations.

Thus the ideas, these categories, are as little eternal as the relations they express. They are historical and transitory products.

Liberal democratic end-of-history triumphalism can feel good, but we need to remember that almost all contemporary politics are in reaction to an incredibly small slice of human history, and the balance of power between interest groups current technology provides isn’t guaranteed by any laws of nature and may slip away in the future as new technology emerges.

There are three passages I think perfectly sum up technological determinism and how I think about its relationship to AI.

First, Joseph Heath makes the point in his essay appreciating Ian M Banks that much of our science fiction more or less pretends technological determinism isn’t real. This is a good example of how technological determinists think, and where they notice mistakes in other people’s thinking:

In fact, modern science fiction writers have had so little to say about the evolution of culture and society that it has become a standard trope of the genre to imagine a technologically advanced future that contains archaic social structures. The most influential example of this is undoubtedly Frank Herbert’s Dune, which imagines an advanced galactic civilization, but where society is dominated by warring “houses,” organized as extended clans, all under the nominal authority of an “emperor.” Part of the appeal obviously lies in the juxtaposition of a social structure that belongs to the distant past – one that could be lifted, almost without modification, from a fantasy novel – and futuristic technology.

Such a postulate can be entertaining, to the extent that it involves a dramatic rejection of Marx’s view, that the development of the forces of production drives the relations of production (“The hand-mill gives you society with the feudal lord; the steam-mill, society with the industrial capitalist.”). Put in more contemporary terms, Marx’s claim is that there are functional relations between technology and social structure, so that you can’t just combine them any old way. Marx was, in this regard, certainly right, hence the sociological naiveté that lies at the heart of Dune. Feudalism with energy weapons makes no sense – a feudal society could not produce energy weapons, and energy weapons would undermine feudal social relations.

Dune at least exhibits a certain exuberance, positing a scenario in which social evolution and technological evolution appear to have run in opposite directions. The lazier version of this, which has become wearily familiar to followers of the science fiction genre, is to imagine a future that is a thinly veiled version of Imperial Rome. Isaac Asimov’s Foundation series, which essentially takes the “fall of the Roman empire” as the template for its scenario, probably initiated the trend. Gene Roddenberry’s Star Trek relentlessly exploited classical references (the twin stars, Romulus and Remus, etc.) and storylines. And of course George Lucas’s Star Wars franchise features the fall of the “republic” and the rise of the “empire.” What all these worlds have in common is that they postulate humans in a futuristic scenario confronting political and social challenges that are taken from our distant past.

In this context, what distinguishes Banks’s work is that he imagines a scenario in which technological development has also driven changes in the social structure, such that the social and political challenges people confront are new.

The relationship between weapons tech and modes of government Heath points out is covered in more detail by George Orwell in You and the Atom Bomb: